Friday essay: Miles Franklin’s other brilliant career – her year as an undercover servant

In the Miles Franklin archive in the State Library of New South Wales there are two brown, cloth-bound volumes, titled, “When I was Mary-Anne, A Slavey”. The thick, handwritten pages are amended with glued paper inserts copied from the missing diary the author of My Brilliant Career kept for roughly a year between April 1903 and April 1904.

In an accompanying summary, on which Franklin based her 1904 letter to the Bulletin about the experience, she wrote:

Some people wonder what domestic servants have to complain about […] No one could understand the depth of the silent feud between mistress and maid without, in their own person, testing the matter …

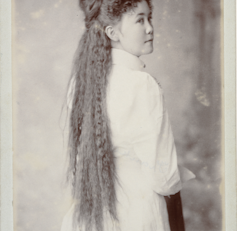

There is a picture of Franklin in the archive too, dressed in her “get up”: a black-and-white tunic and apron, with a lacy parlour cap pinned atop her piled-up brunette hair. The photograph, taken in a studio in Melbourne, is captioned “yr little mary-anne”. She beckons you into her impersonation.

Miles with very long hair.

State Library of New South Wales

Along with the letters Franklin wrote or received during the year, the summary and photo authenticate her little known upstairs–downstairs experiment in Sydney and Melbourne, which she details in the manuscript. She cooked in flammable kitchens, plunged her hands into steaming washing up, and swept the dust that scattered behind her employers’ shoes.

In today’s Instagram culture, it is improbable that a celebrity like Franklin could work incognito and not be recognised. But this was the Edwardian era of the early 1900s, when a photograph was a special occasion and names were known more widely than faces. Franklin loved that a lady she’d once met at a government reception unknowingly flung her coat at her when she opened the door, and that she stoked the fire while guests discussed My Brilliant Career.

Bronte of the bush

Aged 21, Franklin dazzled Australia with her debut novel. Published in 1901, My Brilliant Career inspired young women to write to her about their own frustrations and dreams. She denied her novel was autobiographical, to little effect. She was compared to novelist Charlotte Bronte and to Marie Bashkirtseff, the Russian–Parisian teen artist who declared in her memoir, “I am my own heroine”.

Russian–Parisian teen artist Marie Bashkirtseff, who Miles was compared to.

Musee d’Orsay

Despite Franklin’s later fervent wish that My Brilliant Career’s heroine, Sybylla Melvyn, would be forgotten, the book endured. It became a feminist literary classic, and in 1979 a film, produced by Margaret Fink and directed by Gillian Armstrong. Today, her cultural touchstone continues with her bequest of the Miles Franklin Literary Award and recent stage adaptations of My Brilliant Career. The Stella literary prize is named in her honour, after her first given name, Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin.

Franklin’s iconic success is, however, misleading. Like many authors, she experienced fame and acclaim, but minimal royalties, in part due to an unfair contract for colonial authors with her Edinburgh publisher, William Blackwood and Sons. Books were also a luxury during the punishing Federation drought, which lasted from 1895 to 1902.

Franklin could have married. Her grandmother took every opportunity to remind her she was expected to wed. “Have you found anyone you like better than yourself?” she archly asked.

Instead, she disappeared into undercover journalism.

Stunt girl reporters

Franklin was likely inspired by the “gonzo” women journalists known as “girl stunt reporters”, who disrupted male-dominated journalism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

To prove their journalistic chops, they risked their safety and health to go undercover and expose factory exploitation and illegal abortion clinics. Most famously, New York reporter Nellie Bly feigned hysteria to gain admission to the city’s public women’s mental health institution for ten days in 1887. Their stories captivated audiences, as much as their daring.

American journalist Elizabeth Banks transported the trend to London, where she worked as a servant, leaving her poodle, Judge, with a friend. Her reports in “In Cap and Apron” for the Weekly Sun caused a sensation, and Banks’ memoir Autobiography of a Newspaper Girl was reviewed in Australia in late 1902 and early 1903.

Apart from Catherine Hay Thomson’s investigation of Kew Asylum and Melbourne Hospital in 1886, the “stunt girl reporter” only noticeably appeared in Australia in 1903.

That year, the fledgling New Idea magazine published a series of undercover articles, including about experiences such as working in a tobacco factory and applying for domestic service at an employment agency. Unlike Franklin, the New Idea journalist stopped there, while Franklin spent a full, gruelling year as a servant.

The “servant question” was an ideal local investigation. The newly federated Australia was growing due to the wool industry – “on the sheep’s back”. But in the cities, factories were an alternative engine for young women’s employment rather than domestic service. Fretting “mistresses” complained about the dearth of remaining girls available.

Servants retorted that if they were treated better, perhaps they would stay. One suggested scandalously that mistresses should give references about how they treat servants to prospective hires, pre-dating contemporary suggestions that owners and agencies should prove their fitness as landlords to tenants.

The debate around “the servant question” exposed Australia’s myth of equality. Franklin’s family was no exception. While drought drove her parents off their farm, Stillwater, to a plot in Penrith (then a rural town outside Sydney), they were cultured and educated. Franklin’s wealthy grandmother ran a station in the Snowy Mountains, on which Franklin based the elegant homestead, Caddagat, in My Brilliant Career. A governess or nurse was acceptable, she wrote in her accompanying summary to her manuscript, but “a servant raised considerable horror among my circle”.

Franklin was undeterred. As well as a new writing project, she needed money and a roof if she wanted to live in the city rather than at home. Suffragette Rose Scott, who called Franklin her “spirit child”, invited her to stay. But while Franklin appreciated the support, at times Rose was suffocating.

Revealing the independent streak that would define her life, Franklin wrote, “it was imperative I get work to sustain myself”.

Sufragette Rose Scott called Miles her ‘spirit child’.

State Library of New South Wales

‘This suppression!’

Franklin’s real servant pseudonym was “Sarah Frankling”, a play on her middle name and her surname. “Mary-Anne”, at the time a well known slang name for servants, was only used for the manuscript, to hide identities.

Franklin’s live-in domestic servant positions included kitchen maid, parlour maid and “general” servant. She worked in a terrace she dubbed a “cubby house”, an upmarket boarding house, a harbourside villa, a wealthy merchant home, and mansions in Sydney and Melbourne. Franklin stayed a maximum of two months at each post for a year in total, after which she planned to write.

Senator and High Court judge Richard Edward O’Connor and his large family were her most high-profile employer. Their mansion, Keston, which is close to the prime minister’s Sydney residence, Kirribilli House, and the boarding house around the corner survive, as does the terrace, near Bronte in the city’s eastern suburbs. All are now apartment buildings.

Keston House, Kirribilli, was home to Miles’ most high-profile employer.

City of Sydney Archives

In the manuscript, Franklin recounts that she rapidly lost weight and felt her spirit become “suppressed” by the monotony and tiring nature of servant work. Depending on the number of staff and her duties, she hand-rolled heavy, wet clothes through a washing mangle; served pre-breakfast tea and toast in bed, which she thought was an obscene indulgence; cooked and served full hot breakfasts and dinners daily; waited on guests in the boarding house’s dining room, nicknamed “the zoo”; cleaned the guest rooms and parlours; and helped at high-society balls. She kept fires burning in winter and sweated through heavy housework and cooking in summer.

The hours were brutal. She usually woke at dawn, and only finished after the evening dinners were served, or if she was a kitchen maid, after she cleaned the mess away. Not all her employers offered a luxurious whole afternoon off per week. She worked through burns sustained on the job, and was brought to tears by a mistress who ordered her to change her carefully arranged hair. The house’s Irish cook opined that the mistress was threatened by Franklin’s “toy figure” and “fairy face”.

As the months passed at different employers, fatigue turned to anger, and loneliness to friendships with fellow servants. It is heartening to see a snobby young Franklin mature and change as she rubbed tired elbows with those she previously saw as beneath her status. She cheekily flirted with a lovestruck tradie, just as she traded Shakespearian quips with an intrigued young naval officer staying at the posh boarding house.

When Scott learned Franklin was working as a servant, she chided her for not refusing the conditions as an example to others. However, Franklin knew any insolence or objection meant instant dismissal, ruining her research and current livelihood.

Scott also misread Franklin’s long-term goal – writing the servant book. In her diary, Franklin recorded what she could not say out loud. She cynically noted that “to be sensitive would be unfortunate” for a servant. “The maid must not want for pleasure,” Franklin warned, “because she will have no time to gratify it”. Be presentable but not too pretty, she advised; be polite but not so fancy or fussy to refuse tiny, “ill-aired” servant quarters next to the laundry.

The servant year confirmed her lifelong views of marriage as stifling. Echoing My Brilliant Career, Franklin vented her feminist frustration in the diary entries. She wrote of the terrace’s “Mistress”: “sooth, when a woman of ordinary intelligence gives the whole of her time, brain and energy to the running of a miniature establishment”.

As for the husband, an irritated Franklin wrote that he was “boss of his own backyard and lord of his little suburban dining room”.

Miles as a servant. The servant name she used in her manuscript was ‘Mary Anne’.

State Library of New South Wales

Biographers brush over servant year

Biographies of Miles Franklin have largely followed the traditional “cradle to grave” of her life, in which the critical servant year has been brushed over like a quick sweep of the biographical floor. One of Franklin’s first biographers, Marjorie Barnard, dismissed Mary-Anne as of little interest.

Jill Roe, author of the epic biography Stella Miles Franklin, read the existing Mary-Anne draft manuscript, describing it in her book as Franklin’s “social experiment”. Yet even Roe is succinct about Mary-Anne, compared to other years in Franklin’s eventful life. Roe lists Franklin’s known servant employers, admires her pluck and commiserates over it not being published due to concerns she had defamed her employers. (Franklin’s pseudonyms for her employers were chiffon thin, so easily identifiable.)

There were other intractable problems too with the manuscript, though Franklin may have edited another draft before submitting it for publication. The existing draft is overlong, unwieldy and inconsistent in its point of view. Franklin switches between “I” and later, “Mary-Anne”, as if she fully collapses into her servant life.

Despite her failure to find a publisher for her manuscript, Franklin continued her journalism. She began writing for the Sydney Morning Herald, which suited her fast writing style, and helped her earn money with a pen.

In 1908, Franklin joined the women’s trade union movement and advocated for working women, all the while working on her own novel, writing and resisting the status quo of the Edwardian era. She finally returned to literary acclaim with the award-winning All That Swagger in 1936, a colonial saga of a pioneering family, and another historical series she wrote under the pseudonym “Brent of Bin Bin”.

Upon her death in 1954, tributes reported that “Australian literature lost one of its great figures”.

The ‘servant question’ remains

Franklin’s investigation of the servant question now seems quaint. Appliances have changed from washing mangles and melting iceboxes to sleek stainless steel and glossy white machines that beep and hum in the background.

Yet demand for service remains. “Servants” are still in our lives; they just answer to an app rather than a bell. They clean our houses while we are out, or they are chefs on call who cook meals delivered by mobile waiters on electric bikes and scooters who brave traffic as they dash to door to door. Uber and Dido chauffeurs compete to pick us up from wherever we happen to be.

The exploitation remains, too. At the extreme, the Sri Lankan Embassy in Canberra has been ordered to pay $117,000 in back wages to its domestic servant, paid 90 cents an hour. More broadly, Fair Work last year moved to protect gig workers in the share economy, recognising its endemic lack of rights and risks.

Since Franklin’s Mary-Anne, low-wage service work has been revisited periodically by writers interested in social justice. In 1933, inspired by Jack London, George Orwell chronicled the months he spent impoverished and doing menial jobs in Down and Out in Paris and London.

In 2001, Barbara Ehrenreich published the acclaimed Nickel and Dimed, about working and living on minimum wage. Elisabeth Wynhausen wrote an Australian version, Dirt Cheap: Life at the wrong end of the job market in 2005. Alexandrea J. Ravenelle brought the history full circle in 2019 with her collected stories of 80 gig economy workers in her book, Hustle and Gig. All these authors had similar conclusions to Franklin: low-wage service work is grinding and exploitative.

At its core, the servant question hasn’t changed at all since Franklin’s investigation over a hundred years ago.

Miles Franklin Undercover by Kerrie Davies is published by Allen & Unwin Läs mer…