Donald Trump’s foreign policy might be driven by simple spite – here’s what to do about it

Recent shifts in US foreign policy – particularly regarding tariffs and the war in Ukraine – have sparked debate over what is driving the Trump administration’s decisions. Some of those decisions have appeared so odd that media commentators and even some European officials have wondered out loud if the US government may now even be serving Russian interests.

It’s more likely that US actions simply reflect an aggressive pursuit of what the Trump administration perceives to be America’s interests. Such policies may help rebuild US manufacturing and reorient its military for future tensions with China.

Yet former Trump official Anthony Scaramucci, now co-host of the popular The Rest is Politics US podcast and a bitter opponent of his former boss, has a different take. He argues the US president isn’t – as is sometimes claimed – playing “four-dimensional chess” but acting on “whims” and “eating the chess pieces”.

This raises the possibility that some of Trump’s policies are simply spiteful rather than strategic. My book Spite, published in 2020, examines spite’s psychological roots and its evolution and social impact in citizens, leaders and policy makers. It offers insights into what may now be unfolding on the world stage.

Spite is where we act to harm another person – even at a cost to ourselves. While spiteful actions can be strategic, helping your long-term self-interest, they are often damaging to everyone in both the short- and long-term. Understanding whether spite is involved in US policy decisions is crucial for the world’s ability to respond effectively.

Cooperation — working together for mutual benefit — is humanity’s superpower. We cooperate with people outside our families in a way that other species do not. After the second world war, cooperative alliances, trade agreements and global institutions fostered some degree of shared prosperity.

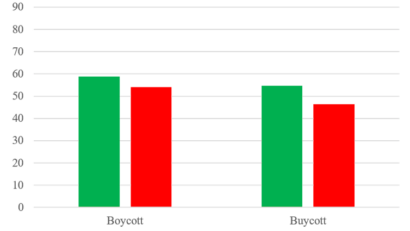

Yet cooperation (I win, you win) is just one of four basic behaviours, alongside altruism (I lose, you win), selfishness (I win, you lose) and spite (I lose, you lose). Trump often frames US cooperation as altruism, claiming America gives and gets nothing in return, making it unfairly exploited.

Sign up to receive our weekly World Affairs Briefing newsletter from The Conversation UK. Every Thursday we’ll bring you expert analysis of the big stories in international relations.

His “America first” policy embraces selfishness, treating international relations as a zero-sum game where there can only be one winner. However, by recasting cooperation as unfair, Trump’s resulting anger may be driving him beyond selfishness into counterproductive spite.

When the US has imposed tariffs on countries, they have generally retaliated in kind with their own tariffs. The result? Everyone suffered. In Trump’s first term, US consumers bore most of the costs of tariffs, while retaliatory tariffs also reduced real incomes abroad.

Economist and former US labour secretary Robert Reich argues Trump’s tariffs are meant “to show the world that he’s willing to harm smaller economies even at the cost of harming the US’s very large one”. This is textbook spite.

Similarly, after tensions between Trump and the Ukrainian president, Volodymyr Zelensky, US actions seemed more focused on punishing Ukraine than advancing US interests. Some argue this hurt US national security as well as Ukrainian security.

The costs and benefits of spite

International relations scholars offer different views on spite. Realists see spite as a rational tool for maintaining power. They emphasise that as long as the US loses less than its rival, it makes a relative gain.

Liberals prioritise absolute gains — arguing that cooperation leads to mutual benefits, even if some gain more than others. They see spite as damaging trade and alliances that ultimately strengthen the US.

Constructivists, who argue that state actions depend on context and perceptions, emphasise that spite’s impact will vary. Spite directed against a major rival may be useful. Yet, spite against smaller allies can undermine trust and long-term cooperation.

Spiteful US tariffs may force weaker allies such as Canada into making concessions. But scholars warn that China, which has far greater economic depth, has both the will and resources to “play a dangerous game of mutual pain and destruction with the United States”.

Ultimately, constant trade wars suggest a desire to dominate and punish rather than pursue strategic self-interest, escalating conflicts rather than solving them. Research on human cooperation shows that winners don’t punish, and that losers “punish and perish”.

The psychology of spite

Spite may be be shaping US policy because Trump’s perceptions, environment and personality are encouraging spitefulness. Spite often results from feeling treated unfairly. The US president has manufactured a sense of unfairness and repeatedly asserts that allies are treating the US “very, very unfairly”.

Donald Trump’s fiery White House exchange wtih Volodymyr Zelensky, February 28 2025.

As China grows, the world is becoming more competitive. Research suggests that increased competition encourages spite. And, in an era of strongman politics, leaders may seek dominance. Spite is one way to dominate others.

Possessing the dark triad of personality traits — psychopathy, narcissism and Machiavellianism — increases your risk of being spiteful. Researchers have argued that Trump scores highly on such traits (although, if true, this is not necessarily bad as narcissism has been linked to some elements of presidential success).

Spitefulness is more common in people who struggle to control their emotions. Trump has been accused of temper tantrums. Even one of his own attorneys is said to have deemed Trump “incapable of testifying because he could not control himself, his emotions”.

Spite isn’t always bad. It can force fairness, boost competitive performance and is linked to creativity. But when spite destroys cooperation – humanity’s superpower – it becomes human kryptonite.

How to prevent spite from shaping policy

To stop spite influencing foreign policy, it’s necessary to address its triggers. This means challenging perceptions of unfairness. Leaders must emphasise the mutual benefits of cooperation. The trust on which cooperation is based must also be rebuilt.

There is also a need to resist dominance-seeking. In hunter-gatherer societies, those who seek dominance are often restrained by the group. International institutions, as well as checks and balances in the US system, need to prevent reckless dominance-seeking from escalating. Reactions to spite must be firm but measured, rather than risking a race to the bottom.

Overall, America’s apparent use of spite to unnecessarily reduce the living standards of its adversaries as well as some allies and even its own citizens is deeply troubling. Yet, were the US to refuse to wield spite against its adversaries it risks allowing a new global power – one potentially hostile to liberal democracy and human rights – to shape the world order.

Aristotle argued that the virtuous person gets angry for the right reasons, at the right time, in the right way. America must learn to do the same. Läs mer…