The Economy for the Common Good (ECG) is an alternative to the existing economic model of capitalism, including the pursuit of profit and constant growth. The ultimate goal is a good life for all people. The idea: the state supports companies that produce in an environmentally friendly way and pay their employees fairly. Through favorable loans and tax breaks, they receive a clear advantage and can thus operate even more successfully. Piece by piece, this could lead to a sustainable and socially just economic system.

Let’s imagine that a small café, a local carpentry shop and a family bakery are suddenly more successful than the branches of the large global corporations. The reason: the state supports them with favorable loans, investment aid and tax breaks because they operate more sustainably, socially and fairly. The corporations, on the other hand, have to pay higher taxes because they exploit their employees and destroy nature. This deliberately gives small businesses a clear advantage over corporations and enables them to assert themselves on the market with their fair and sustainable products.

A utopia? From today’s perspective, yes. But in the sense of the Economy for the Common Good, this is what our economic reality could look like.

[embedded content]

Economy for the Common Good Explained: What is it?

The Economy for the Common Good (ECG) is an alternative to the existing economic model of capitalism. The primary goal is a good life for all people, and not the maximum enrichment of a few company owners. It is an ethical market economy based on basic human values. The focus is on human dignity, solidarity and justice, ecological sustainability, transparency and co-determination. Values that are also shared by almost all democratic constitutions.

One of the strengths of the Economy for the Common Good is that it links to core elements of the capitalist market economy: corporations, credit, trade, markets, property. However, it transforms these elements by consistently placing them at the service of overarching values—human dignity, solidarity, justice, sustainability, democracy. It is therefore transformation and evolution, not “disruption” or “system change.” (Christian Felber, founder of the Economy for the Common Good)

These overarching values are only a proposal. The concept envisages that they will be (further) developed jointly in a democratic process.

Sustainability for People, Environment, and Economy

The Economy for the Common Good understands sustainability as being, not only the resource-conserving use of nature, but also respect for human dignity as well as free and successful economic activity as part of an ethical market economy.

The three Pillars of Sustainability

Upholding human dignity

Respectful treatment of nature

Entrepreneurial freedom and success within the framework of an ethical market economy

ECG leads to more sustainability, as it promotes those companies that operate in an environmentally friendly and socially responsible manner. Through loans, investments and tax breaks, they gain a clear advantage over others and thus prevail with their products on the market.

Following this simple principle, it would simply no longer be worthwhile to disregard human dignity, destroy the environment or drive inequality in society for the profits of a few. Step by step, this could lead to an economic system in which careful use of our finite resources pays off—while reckless and exploitative behavior does not.

Many people are now looking for meaningful work. Sustainability is particularly important—especially among the younger generation. This is another advantage for companies that focus on the common good: many of their employees feel significantly more satisfied they see their work as making a contribution to the common good.

The “common good balance sheet” measures exactly how much a company contributes to the common good.

Common Good Economy Goals: Democratize the economy

Through a new economic order and a fundamentally new way of thinking about business, the common good economy aims to achieve a good life for all. This is its ultimate goal. Everything is to be discussed anew and decided democratically:

ECG Goals: Democratize the Economy

Should a CEO really earn 300 times as much as an employee? Or wouldn’t 10 times be fairer? Of course, there should be more pay for more responsibility. But at the moment there is a lack of proportionality. Because such high salary differences endanger social cohesion.

Shouldn’t toxic sprays be banned altogether, even if a global corporation is resisting one with all its might? After all, every single person bears the health consequences. Wouldn’t it be fairer if they were the ones to decide?

Eight billionaires own more than the poorer half of the world’s population. Is that still fair? Or do we need a wealth cap, higher inheritance taxes and a fairer distribution of property?

How high should the minimum wage be? Is 12 euros per hour (Germany) enough? Is it okay that there is none at all in Austria?

The Economy for the Common Good wants to put control over our future back into the hands of democracy. An accumulation of capital, money and consequently power should only be possible to a limited extent. Where this limit lies, all people should decide together.

The common good balance sheet: This is how it is assessed

With the common good balance sheet, a company, university, city, or municipality can measure its contribution to the common good.

Contribution to the Common Good

Are the raw materials used mined in an environmentally friendly way?

Are there human rights violations in the supply chains?

Does the customer benefit take precedence over the company’s own sales aspirations?

Are all those involved paid fairly?

Is transparency ensured in dealings with employees?

One of these companies is the sporting goods manufacturer Vaude. Vaude pays attention to the highest ecological standards in textile production. With the Common Good balance sheet, the company can measure the resulting contribution to the common good.

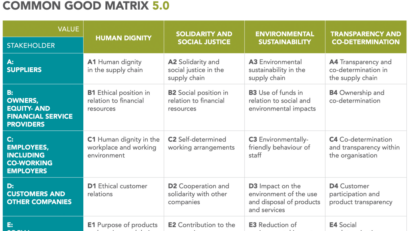

The Common Good Matrix (graphic: www.ecogood.org/)

The Common Good Balance Sheet is based on the Common Good Matrix and rates companies in 20 categories with + or – points. Plus points are awarded, for example, for resource-conserving and environmentally friendly business practices, fair wages and social working conditions. Minus points, on the other hand, are awarded for environmentally harmful behavior or disregard for human rights. The more plus points a company has, the more it contributes to the common good.

The Economy of the Common Good advocates that such a balance sheet would be mandatory for companies and, above all, would have legal and economic consequences. Companies with a high score would receive certain advantages, such as lower taxes, more favorable investments, or would be given preference in the awarding of public contracts. This would create concrete incentives to operate and produce in a sustainable and socially responsible manner.

Around 1,000 companies in 35 countries are already drawing up a common good balance sheet and have decided to pursue social goals beyond mere profit maximization. These include well-known companies such as Vaude, Sonnentor, Windkraft Simonsfeld, the Trumer brewery and the Freistadt brewery community.

Pros & cons of the Economy of Common Good: advantages and disadvantages for society

The basic values of the common good economy (human dignity, solidarity, justice, sustainability, and democracy) result in the following benefits: Pros & Cons of the Economy of the Common Good

Sustainability: By committing to sustainable and resource-conserving production, we save our planet.

Transparency: The common good balance sheet makes the behavior of companies comprehensible and transparent for society.

Solidarity and justice: Social cohesion and solidarity with one another grow as inequalities and injustices are reduced.

Equality of opportunity: A wealth cap (for legal entities: e.g., a limited liability company, stock corporations or trade associations) reduces the differences between rich and poor. This leads to greater equality of opportunity. This is because wealth and private ownership contribute significantly to economic, social and also political inequality in a society. Today, the rule is: those who are rich get richer. Those who are poor remain poor.

More democracy: In Austria, 90 percent want a new economic order—in Germany, the figure is 88 percent (Bertelsmann Foundation survey, 2012). People want change, but in the current model they have no voice. It’s quite different in the common good economy: here, they would vote together on every aspect of the economy. Everything would be up for debate: Is it fair, for example, for a manager to earn 300 times that of a regular employee? Wouldn’t 10 times be enough?

Less lobbying: Lobbying and corporate influence on political decisions would simply no longer be possible, as the common good would be the ultimate goal. As a result, global corporations and extremely wealthy individuals would lose the basis of their power and influence.

Human dignity: No more exploitation, as the economic consequences (more taxes and duties) would make it no longer worthwhile.

Disadvantages would arise mainly for those who exploit the current situation and profit from the fact that people and the environment are exploited, that political influence is possible and that there are no real consequences for it (yet).

The Criticism: The Effort and the limited Freedom

The Austrian Chamber of Commerce criticizes the bureaucratic effort that this could create. Not only would one have to draw up a common good balance sheet for every company, but one would also have to define the tax and social advantages and disadvantages that result from this.

But if you think back, you will see that the introduction of general accounting also involved a lot of effort. So should we really ask ourselves whether it would be too burdensome? Or shouldn’t we better ask: does a company benefit the environment, peace, people? Does it contribute to the general welfare of society, or does it do more harm?

[embedded content]

Of course, a new balance sheet would be a costly undertaking—but one that would be worthwhile for companies and society. It would help them reflect on their own actions, classify them and, if necessary, adjust them to contribute to a better society. Which, at the end of the day, is also in their best interest.

It is also often criticized that the common good economy would restrict the freedom of companies and individuals too much. However, it is questionable how much of a restriction there can be when entrepreneurial freedom means the exploitation of people and nature.

Our society is built on restrictions—that’s the only way coexistence and freedom work. For example, we do not race through the inner city at 200 km/h because that would be too dangerous for everyone involved. We also do not solve conflicts with violence, but in court. Restrictions are necessary—but only we as a society should decide on them.

The Economy for the Common Good: Examples

Worldwide, there are nearly 60 practicing cities and communities, 175 active regional groups, and 200 universities committed to the common good economy. These people have chosen it because they no longer want to watch large corporations destroy the environment and erode democracy. They want to see meaning in their work again, and working together for a better society gives them just that. The reasons and the exemples for their commitment are numerous and could not be more different, but they all have one thing in common: dissatisfaction with the current situation and the will to change something.

Good Practices:

Valencia: Since 2021, the autonomous region has been promoting companies that produce sustainably and that have drawn up a common good balance sheet. A total of 700,000 euros in funding will be awarded.

Hamburg: In the future, public companies will be required to comply with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. To monitor compliance, they are to draw up a common good balance sheet.

Common good balance sheet in banks: Vorarlberger Landesversicherung, Raiffeisenbank Lech and Dornbirner Sparkasse already prepare common good balance sheets. The pioneer in Germany was Sparda-Bank München. Former Chairman of the Board Günter Grzega: “In the course of our common good reporting, my successor abolished all bonus payments at Sparda-Bank München. As a result, two out of a total of 700 employees left the company. And that was a good thing.”

Common Good account: The “Gemeinwohl Konto” is a cooperative project between the “Genossenschaft für Gemeinwohl” and the environmental center of Raiffeisenbank Gunskirchen. The goal is to use money specifically for undertakings that serve the common good and thereby contribute to a change in the monetary and financial system. This is made possible by a rather simple step: a separate accounting cycle guarantees that money to the value of all deposits in common good accounts is allocated as financing for common good-oriented projects. This way, all account holders know that their money contributes to the common good.

Faced with the climate crisis, the gap between rich and poor, and the crisis of confidence in politics and democracy, transforming the current economic system towards a common good economy could defuse, if not solve, many global problems.

Constraints will result from this. However, these restrictions will not curtail our freedom, but will set in motion a democratic process that can make all our lives better. Läs mer…