Misstänkt mord i Hässleholm – en anhållen

En person har hittats död i en bostad i Hässleholm. Dödsfallet rubriceras som mord eftersom omständigheterna är… Läs mer…

Nyheter och länkar - en bra startsida helt enkelt |Oculus lyx vitae

En person har hittats död i en bostad i Hässleholm. Dödsfallet rubriceras som mord eftersom omständigheterna är… Läs mer…

Vad får lyxlirarna för pengarna? Läs mer…

Terrorstämplade Hamas dödade 378 människor på musikfestivalen Nova, enligt en utredning från Israels militär av… Läs mer…

Aftonbladet gav sig ut på stan Läs mer…

Det mindre flygplan som störtade i en sjö utanför Bergen i Norge i tisdags har hittats på 30 meter djup. Läs mer…

In February, the world’s richest man, Elon Musk, wielded a chainsaw at a conservative gathering as he gleefully spoke of Läs mer…

Warner BrosThe White Lotus season three returns to familiar territory: an exotic escape, privileged and powerful guests, the supposed Läs mer…

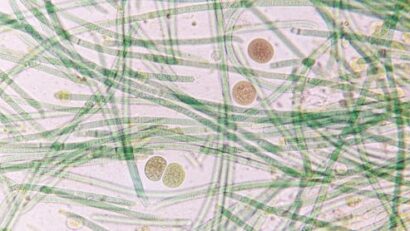

Association of two Cyanobacteria (Oscillatoria sp. and Chroococcus sp.). Ekky Ilham/ShutterstockThere are roughly a trillion species of microorganisms on Earth Läs mer…