Good boy or bad dog? Our 1 billion pet dogs do real environmental damage

William Edge/ShutterstockThere are an estimated 1 billion domesticated dogs in the world. Most are owned animals – pets, companions Läs mer…

Nyheter och länkar - en bra startsida helt enkelt |Oculus lyx vitae

William Edge/ShutterstockThere are an estimated 1 billion domesticated dogs in the world. Most are owned animals – pets, companions Läs mer…

Detta inlägg post publicerades ursprungligen på denna sida this site Läs mer…

skynesher/Getty ImagesThe door to tertiary education will likely close for some students now changes have kicked in for the Läs mer…

Colum McCann Bloomsbury Publishing/ShutterstockAs with his previous novel Apeirogon (2020) and the much-garlanded Let the Great World Spin (2009), Colum Läs mer…

ShutterstockPop quiz: name the world’s most famous trio? If you’re a foodie, then your answer might have been breakfast, Läs mer…

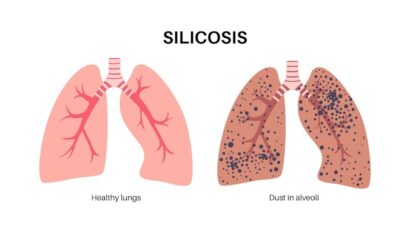

Around 10% of underground tunnel workers in Queensland could develop silicosis, our new study has found. Silicosis is a serious, Läs mer…

With just over three weeks to go until the federal election, both major parties are trying to position themselves as Läs mer…

Election promises are a mainstay of contemporary politics. Governments cite kept commitments as proof they can be trusted, while oppositions Läs mer…