Royal Mail trials postbox with parcel hatch, solar panels and barcode scanner

Detta inlägg post publicerades ursprungligen på denna sida this site Läs mer…

Nyheter och länkar - en bra startsida helt enkelt |Oculus lyx vitae

Detta inlägg post publicerades ursprungligen på denna sida this site Läs mer…

skynesher/Getty ImagesThe door to tertiary education will likely close for some students now changes have kicked in for the Läs mer…

Colum McCann Bloomsbury Publishing/ShutterstockAs with his previous novel Apeirogon (2020) and the much-garlanded Let the Great World Spin (2009), Colum Läs mer…

ShutterstockPop quiz: name the world’s most famous trio? If you’re a foodie, then your answer might have been breakfast, Läs mer…

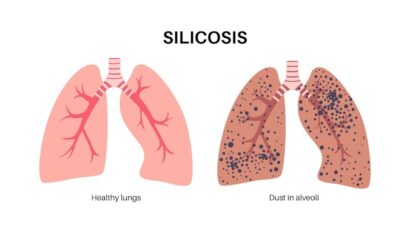

Around 10% of underground tunnel workers in Queensland could develop silicosis, our new study has found. Silicosis is a serious, Läs mer…

With just over three weeks to go until the federal election, both major parties are trying to position themselves as Läs mer…

Election promises are a mainstay of contemporary politics. Governments cite kept commitments as proof they can be trusted, while oppositions Läs mer…

The federal election should be an earnest contest over the fundamentals of Australia’s climate and energy policies. Strong global Läs mer…