Vancouver SUV attack exposes crowd management falldowns and casts a pall on Canada’s election

A car attack at a Filipino street festival in Vancouver just two days before Canada’s federal election has killed at Läs mer…

Nyheter och länkar - en bra startsida helt enkelt |Oculus lyx vitae

A car attack at a Filipino street festival in Vancouver just two days before Canada’s federal election has killed at Läs mer…

EV batteries are made of hundreds of smaller cells. IM Imagery/ShutterstockAround the world, more and more electric vehicles are hitting Läs mer…

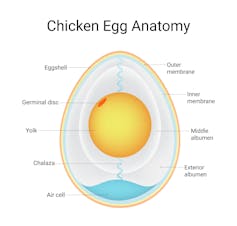

We’ve all been there – trying to peel a boiled egg, but mangling it beyond all recognition as the hard Läs mer…

Stenko Vlad/ShutterstockE-cigarettes or vapes were originally designed to deliver nicotine in a smokeless form. But in recent years, vapes Läs mer…

Apple TVIn the second episode of Apple TV’s The Studio (2025–) – a sharp satirical take on contemporary Hollywood Läs mer…

Australia is running out of affordable, safe places to live. Rents and mortgages are climbing faster than wages, and young Läs mer…

The year is 1972. The Whitlam Labor government has just been swept into power and major changes to Australia’s immigration Läs mer…

Major parties used to easily dismiss the rare politician who stood alone in parliament. These MPs could be written off Läs mer…