Uncertainty and pessimism abound. Will fear be enough to push Dutton into office?

Tony Abbott was once unelectable. So were Donald Trump and Boris Johnson. And so was Peter Dutton, not so Läs mer…

Nyheter och länkar - en bra startsida helt enkelt |Oculus lyx vitae

Tony Abbott was once unelectable. So were Donald Trump and Boris Johnson. And so was Peter Dutton, not so Läs mer…

Stokkete/ShutterstockWhen Auckland mayor Wayne Brown said in 2022 that the Auckland Art Gallery had the foot traffic of a Läs mer…

The first budget speech of Ghana’s new government on 11 March painted a picture of an economy in crisis, facing Läs mer…

Democracy implies precise rules of operation, but also a way of being, or what the Greeks called an ethos. (Shutterstock)It Läs mer…

The active and ongoing global spread of avian influenza virus has impacted more than 14 million birds in Canada and Läs mer…

The first months of Donald Trump’s presidency have been defined by a single word: tariffs. He has framed tariffs as Läs mer…

Owen Cooper plays Jamie Miller in Adolescence which looks at the experiences of youth at a British school, showcasing their Läs mer…

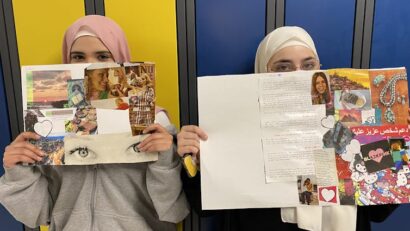

“For Eid we have to call in sick and I don’t like that. You should have the day off Läs mer…