Boycotting U.S. products allows Canadians to take a rare political stand in their daily lives

In the middle of a trade war with the United States, Canadians have started showing strong support for their country by changing their consumer habits. Shoppers have begun shunning all sorts of American products and rallying behind the “Buy Canadian” movement.

By snubbing American products and purchasing Canadian ones, shoppers are engaging in acts of “political consumerism.”

Political consumerism is the idea that people make purchasing decisions based on political reasons. There are two main forms of political consumerism: boycotting, which is avoiding the purchase of certain products and services for political reasons, and buycotting, which involves purchasing certain products and services due to political reasons.

For example, labour issues, animal rights, racial or sexual discrimination, the environment and religion are all political issues that may cause a person to change their purchasing habits. The reasons a person may participate in an act of political consumerism will also differ depending on the country they live in and their political ideology.

A review of 66 survey-based studies that a colleague and I conducted found that the people who participate in acts of political consumerism tend to have left-wing or liberal views. However, this finding may be due to the questions that survey participants were asked — such as focusing on boycotting and primarily listing left-wing motives as reasons to participate in political consumerism.

Those on the left may be motivated to participate in political consumerism due to moral issues, such as concerns about harm and fairness. At the same time, those on the right may engage in political consumerism due to issues of authority, loyalty and purity.

In the context of the U.S.-Canada trade war, those on the right may be particularly motivated to participate in political consumerism due to their loyalty to group identities — such as patriotism for their country. On the other hand, left-wing consumers may be motivated to participate as they may consider the tariffs to be unfair.

Boycotting and buycotting

In January 2023, a colleague and I conducted a survey of five countries — including the U.S. and Canada. The survey’s aim was to examine participation rates in political consumerism based on a sample that matched each country’s official statistics for age, gender and education.

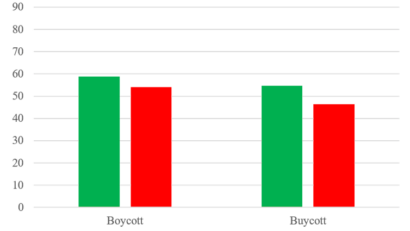

A total of 1,500 participants were surveyed separately in Canada and the U.S. About half of respondents in both Canada and the U.S. reported participating in boycotting and buycotting. Around 55 per cent of Americans participated in buycotting compared with 46 per cent of Canadians.

A comparison of the per cent of American and Canadian survey respondents who participated in acts of political consumerism.

Shelley Boulianne, Author provided (no reuse)

Those who purchased products and services for political reasons (buycotted) were asked about the importance of pride in one’s country as a motive. Americans were slightly more likely to report pride as an important motivation to buycott compared to Canadians.

Contrary to previous studies, the survey also found that boycotting and buycotting were more common among right-wing Americans, who rated national pride as their motivation for buycotting more often than moderates or left-wing Americans.

In Canada, left-wing respondents were more likely to report boycotting. There were no ideological differences in who was most likely to buycott. But, like Americans, right-wing Canadians were more likely to report pride as a motive to buycott compared to moderates or left-wing Canadians.

While the data was gathered before the U.S.-Canada trade war, the findings suggest that Americans and Canadians will participate in the calls to buy American or Canadian goods, respectively. Pride will likely be a strong motivation for those on the right, especially for Americans.

Taking a stand

Since the start of the trade war, Canadian citizens have increasingly been encouraged to buy Canadian products to show their support for their country’s position.

Some retailers are adding ‘Made in Canada’ labels to products.

(Shutterstock)

In some grocery stores, U.S. produce is being left to wilt — with Canadians instead choosing to purchase fruits and vegetables grown either in Canada or in other countries. Some retailers have also started adding stickers next to Canadian-made products.

But though much of the research on political consumerism focuses on boycotting and buycotting consumer products, there are other ways to participate.

Read more:

Does cancelling a trip to the U.S. really send a political message, or is it just hurting local tourism?

In particular, citizens may choose to forego travel to a certain country, as tourism is an important dimension of political consumerism. Reports suggest this is already happening, with the number of Canadians travelling to the U.S. already down. Some Canadian citizens have also designed apps to identify products originating in their home country — as observed in the ongoing trade war.

While some may question the efficacy of boycotting and buycotting campaigns, these activities are one of the few ways for citizens to engage in politics on a daily basis. There are also few opportunities for the average person to engage with politics at an international level. This makes political consumerism an important activity.

Some scholars discount political consumerism as a form of political participation because it’s not connected to the government. However, amid the current U.S.-Canada trade war, political consumerism may be directly linked to government decisions. Citizens can use the marketplace to influence the outcome of the trade war. Läs mer…