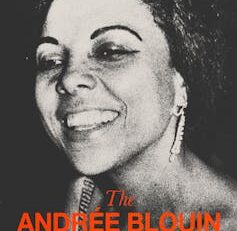

Africa’s newest book prize is named after Andreé Blouin: who was she?

Andrée Blouin was a political activist and writer from the Central African Republic. Until recently, her name hardly ever appeared in the grand narratives of Africa’s liberation.

When she died in 1986, her passing was hardly in the news – a stark contrast to her pivotal role as an adviser and campaign strategist to newly independent African leaders in Algeria, both Congos, Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, Guinea and Ghana.

She was more than a participant. She was an organising force, an architect of resistance, a strategist who shaped the fight against colonial rule. Yet, like many women in African history, her contributions faded into the margins, overshadowed by the men she helped empower.

Eve Blouin/Inkani Books

Interest in Blouin has been rekindled. She is featured in the Oscar-nominated documentary Soundtrack to a Coup d’État about DRC independence leader Patrice Lumumba. She worked as his speechwriter and chief of protocol.

And her memoir My Country, Africa: Autobiography of the Black Pasionaria, long out of print, was re-released and is now widely available.

Now a new annual book award called the Andrée Blouin Prize has been launched in her honour by a South Africa-based publishing house, Inkani Books. Its mission is to amplify the voices of African women, cisgender and transgender, writing about history, politics and current affairs from a left perspective.

For me as a literary historian who has been preoccupied with archives of marginal historical figures, this activation of Blouin powerfully highlights her legacy. It also invites new engagement with her work.

Who was Andrée Blouin?

Blouin was born in 1921 in Central African Republic but from the age of three she was placed in an orphanage in neighbouring Congo Brazzaville. She ran away when she was 14 and so began a life of rebellion.

She would grow up to be a formidable political operator. Her reach touches many parts of Africa. For her, the struggle was not just local, it was everywhere. As a multilingual person, she spoke a dozen languages, a gift that allowed her to easily move between places and political contexts.

Her political awakening was deeply personal – she was radicalised by her son’s death from malaria in a colonial hospital in 1942. He had been denied life-saving medication. Colonialism, she realised, was not just her own misfortune but a system of evil suffocating African lives.

Verso Books

Today history is vindicating this fascinating historical figure. This is happening through the wealth of archival material – photographs, videos, interviews and texts – that places her at the centre of political action. The image of African liberation tends to be men in suits. And yet a smiling Blouin can be seen with them, side by side, even addressing large crowds.

It is thanks to the refusal of this archive to be repressed that we can review moments that shaped African liberation history. And appreciate the roles that women like Blouin played.

Behind the prize

African literary prizes have seen significant growth in recent years, both in number and influence. They play an important role in promoting African literature, offering recognition and financial support to writers, and shaping the literary canon.

They can also address the need for dedicated platforms that amplify underrepresented voices.

Inkani Books describes itself as a “people’s movement-driven publishing house”. It is introducing The Andrée Blouin Prize in her honour. The impetus for the prize, according to Inkani’s publishing director Efemia Chela, was to directly challenge erasure of women in history and in political writing.

She explains:

This prize is not just an accolade; it is a reclamation of space, a declaration that African revolutionary women’s narratives will no longer be sidelined.

The publishing house, established less than five years ago, has been reissuing popular books about revolutionary figures. These include the likes of Thomas Sankara, Kwame Nkrumah, Amílcar Cabral and Frantz Fanon. These men are often celebrated for their heroism and intellectual contributions to pan-African ideas about freedom, politics and revolution.

Blouin in Time magazine, 1960.

Time/Terence Spencer/Courtesy Eve Blouin

The Andrée Blouin Prize is a bold act of reclamation, ensuring that the narratives of African revolutionary women are no longer overlooked but recognised, celebrated and centred.

In fact, this is an invitation for contemporary women to write themselves into literary history.

The inaugural winner will receive a $2,000 advance and a publishing contract with Inkani. The prize is open to all women across Africa and is dedicated to showcasing and celebrating the continent’s diverse and vibrant experiences.

It is part of a broader movement challenging historical exclusions in African publishing. Literary production is dominated by big multinational publishing companies that determine reading tastes and trends.

Last year, Nigeria-based Cassava Republic Press launched the Global Black Women’s Non-Fiction Manuscript Prize to spotlight exceptional works by Black women.

Read more:

African literary prizes are contested – but writers’ groups are reshaping them

While African publishing has not always been welcoming to women writers, a shift is underway. Writers like Nigeria’s Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Zimbabwe’s NoViolet Bulawayo, Uganda’s Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi, and Zambia’s Namwali Serpell are now among the most influential voices shaping African literature today. Läs mer…