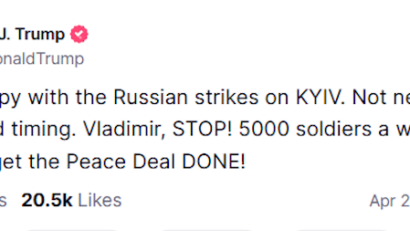

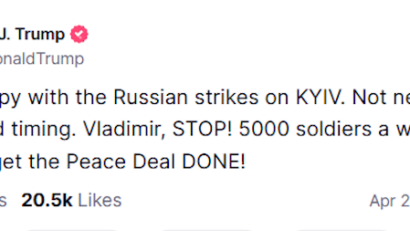

Ukraine’s path to peace appears to be rapidly disappearing

It’s getting hard to figure out who all the US-sponsored talks over ending the conflict in Ukraine are supposed to Läs mer…

Nyheter och länkar - en bra startsida helt enkelt |Oculus lyx vitae

It’s getting hard to figure out who all the US-sponsored talks over ending the conflict in Ukraine are supposed to Läs mer…

What a difference a dictator makes. Some world leaders get a rough ride in their Oval Office meetings with Donald Läs mer…

You have to marvel at Donald Trump’s prescience. After his announcement of America’s new tariffs regime on April 2, “liberation Läs mer…