A 1930s’ movement wanted to merge the US, Canada and Greenland. Here’s why it has modern resonances

A movement that wanted to merge North America into one nation and extend its borders as far as the Panama Canal might sound incredibly familiar. But this group, called the “technocracy movement”, was a group of 1930s nonconformists with big ideas about how to rearrange US society. They proposed a vision that would get rid of waste and make North America highly productive by using technology and science.

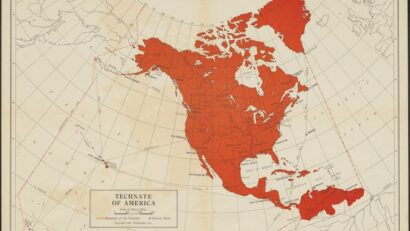

The Technocrats, sometimes also called Technocracy Inc, proposed merging Canada, Greenland, Mexico, the US and parts of central America into a single continental unit. This they called a “Technate”. It was to be governed by technocratic principles, rather than by national borders and traditional political divisions.

These ideas seem to resonate with some recent statements from the Trump administration about merging the US with Canada. Meanwhile, the US Department of Government Efficiency (Doge) set up by Trump and led by tech billionaire Elon Musk, has also outlined a vision of efficiency cuts by slashing bureaucracy, jobs and getting rid of leaders of organisations and civil servants he thinks are advancing “woke” values (such as diversity initiatives). This slash-and-burn approach also fits with some of the ideas of the Technocrats.

In February, Musk said: “We really have here rule of the bureaucracy as opposed to rule of the people — democracy”. The Technocrats viewed elected politicians as incompetent. They advocated replacing them with experts in science and engineering, who would “objectively” manage resources for the benefit of society.

“The people voted for major government reform, and that’s what the people are going to get,” Musk told reporters after visiting the White House last month.

What did the Technocrats want to get rid of?

The 1930s’ movement was an educational and research organisation that advocated for a fundamental reorganisation of political, social and economic structures in the US and Canada. It drew on a book called Technocracy published in 1921 by an engineer called Walter Henry Smyth, which captured new ideas about management and science.

The movement gained significant attention during the Great Depression, a period of mass unemployment and economic problems lasting from 1929 to 1939. This was a time when widespread economic failures prompted radical ideas for systemic change. Technocracy appealed to those who saw technological advancements as a potential solution to economic inefficiency and inequality.

The Technocrats gained traction largely due to the work of Howard Scott, an engineer and economist, along with a group of engineers and academics from Columbia University. In 1932, Scott founded the Technical Alliance, which later evolved into Technocracy Inc.

Scott and his followers held lectures, published pamphlets and attracted a significant following, particularly among engineers, scientists and progressive thinkers. The movement may have influenced the design of future concepts such as planned communities and economies using more automation.

The movement’s ideological foundation was built on the belief that industrial production and distribution should be managed scientifically. Advocates argued that traditional economic systems such as capitalism and socialism were inefficient and prone to corruption, but that a scientifically planned economy could ensure abundance, stability and fairness.

An image from the Cornell University collection on the Technocracy movement.

Cornell University – PJ Mode Collection of Persuasive Cartography

In the 1930s, members of Technocracy Inc sought to replace market-based economies and political governance with a system where experts made decisions based on data, efficiency and technological feasibility. Technocrats aimed to regulate consumption and production based on energy efficiency, rather than market forces.

Technocrats also believed that mechanisation and automation could eliminate much of the need for human labour, reducing work hours while maintaining productivity. Goods and services would be distributed based on scientific calculations of need and sustainability.

While the movement saw rapid growth in the early 1930s, it quickly lost momentum by the mid-to-late 1930s. Echoing some of the concerns of contemporary Americans, critics feared that a government run by unelected experts would lead to a form of authoritarian rule, where decisions were made without public input or democratic oversight.

Technocracy reborn?

But are we seeing a rebirth of some of these kinds of ideas in 2025? Musk has a familial connection with the movement, so is likely to be aware of it. His maternal grandfather, Joshua N. Haldeman was a notable figure in the technocracy movement in Canada during the 1930s and 1940s.

Musk’s ventures, such as the electric car giant Tesla, his space programme SpaceX, and neurotechnology company Neuralink prioritise innovation and automation, which aligns with the Technocrats’ vision of optimising human civilisation through scientific and technological means.

Tesla’s push for autonomous vehicles powered by renewable energy, for instance, chime with the movement’s early aspirations for an energy-efficient, machine-managed society. Additionally, SpaceX’s ambition to colonise Mars reflects the belief that technological ingenuity can overcome the limitations of living on Earth.

What Trump would disagree with

There are some significant differences between the current US government and the Technocrats, however. Musk’s approach to commerce remains firmly embedded in the free market.

His ventures thrive on competition and private enterprise rather than that of centralised, expert-led planning. And while the Technocrats believed in the abolition of money, wages and traditional forms of trade, the Trump administration clearly doesn’t.

Trump believes that politicians like him should run the country, along with partners such as Musk. Technocrats worried about elected politicians being driven by self-interest, but the current US administration seems to value mixing business interests with government decisions.

Although the technocracy movement never became a dominant force, its ideas influenced later discussions on topics such as scientific management and economic planning. The concept of data-driven governance championed by the Technocracy movement is part of modern planning, especially in areas like energy efficiency and urban planning.

The rise of AI and big data has reignited discussions about the role (and reach) of technocracy in modern society. In countries including Singapore and China governance is dominated by departments headed by those with technological backgrounds, who gain an elite status.

In the 1930s, the Technocrats faced significant criticism. The unions, more powerful than today, were almost entirely supportive of the progressive New Deal and its protection of workers’ rights, rather than the Technocrats. The US public’s resurgent belief in the US government during the New Deal era was far greater than today’s declining support in its political institutions, so those institutions would have been better equipped to resist challenges than they are today.

The technocracy movement of the 1930s may have faded, but its central ideas continue to shape contemporary debates about the intersection of technology and governmental planning. And, possibly, who should be in charge. Läs mer…