Detta inlägg post publicerades ursprungligen på denna sida this site ;

Date:

Author: John Gledhill, Associate Professor of Global Governance, University of Oxford

Original article: https://theconversation.com/language-of-peace-why-talk-of-making-deals-rather-than-reaching-agreements-is-not-helpful-255451

Upon returning to the US after his symbolically powerful meeting with Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, at St Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican, President Donald Trump told reporters: “I think [Zelensky] wants to make a deal.” He also called for the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, to “sit down and sign the [peace] deal” that is reportedly in the works.

Such talk of “deals” has been common in recent months. Indeed, as international engagement with conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza has intensified, there has been a sharp spike, globally, in use of the term “peace deal”. At the same time, data from Google Trends suggests there has not been a similar increase in talk of “peace agreement[s]”.

This is perhaps surprising as, up to now, language surrounding peace negotiations has focused on building agreements, not deals. A search of the PA-X Peace Agreements database at the University of Edinburgh identifies more than 800 separate peace accords since 1990 that include “agreement”“ in their title. A similar search for the term ”deal” returns one record.

Why, then, has there been a sudden change in the way we are talking about peace?

It is hard to get past the idea that this recent linguistic turn reflects global adoption of more transactional language – of the sort Trump uses when approaching diplomacy as “the art of the deal”.

On Ukraine, for example, Trump has made continued US engagement contingent on Kyiv striking a minerals deal with Washington, while also hoping that “Russia and Ukraine will make a deal” as a precursor to “mak[ing] a fortune” by doing “big business” with the US.

The US president’s response to the intractable conflict in Gaza has also been built around the language of deals. This has included a vision of US support for reconstruction as a real estate transaction in which Gaza would be redeveloped into “the Riviera of the Middle East”. Trump also asserted that he could “make a deal” with Jordan and Egypt to take in displaced Palestinians, whose right of return to Gaza would not be guaranteed.

But while Trump’s rhetoric has been influential, he does not bear sole responsibility for changing the way we talk about peace. Global leaders have also adopted transactional language. In March, the UK prime minister, Keir Starmer, called for a “coalition of the willing to defend a deal in Ukraine”, and the Nato secretary-general, Mark Rutte, repeatedly referred to the prospect of a “peace deal” when talking to the press after a meeting with Zelensky in Odesa earlier this month.

So is this merely a semantic shift, or does it matter for peace in practice?

If the words we use not only reflect our understanding of issues but also shape understandings, then replacing discussion of peace “agreements” with talk of peace “deals” matters a lot. It is arguably problematic in two ways.

Settling on a solution

First, the idea of a peace “deal” is built on a narrow view of conflict dynamics. It’s a view in which disputes over material interests drive war – and bargaining over those interests can bring an end to war.

While material interests certainly matter, they are not the whole story. Questions of national self-identity, political discrimination, collective emotions and more can all underwrite the onset, persistence and eventual settlement of armed conflicts.

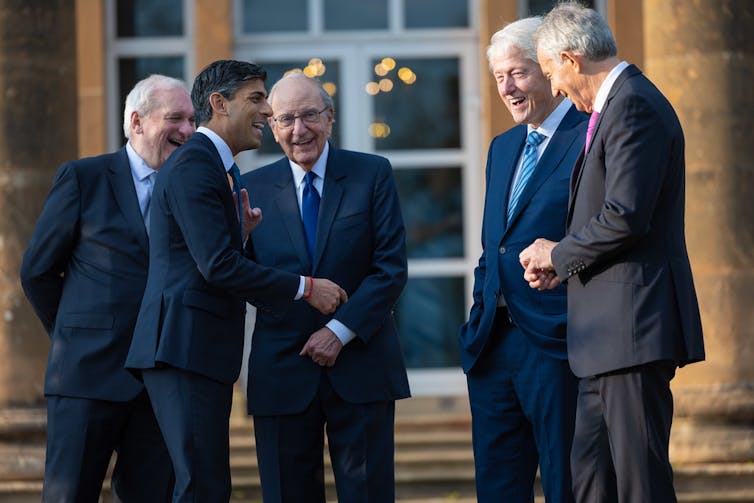

Simon Walker/No 10 Downing Street

Failure to incorporate consideration of these factors into peace negotiations by focusing on deals alone risks alienating conflict parties for whom material interests are just one issue at stake. Such alienation can reduce the likelihood of those parties engaging meaningfully with peace talks, and thus the likelihood of a negotiated settlement emerging.

Second, even if conflict parties are willing (or feel compelled) to sign up to transactional peace deals, then such arrangements may be fragile. After all, “deals” are about parties coming to arrangements that best meet their material interests at a particular point in time, given a prevailing distribution of power and resources. But if the interests, power or resources of one or more conflict parties later shifts, then those parties may choose to break the deal.

Of course, peace “agreements” can also be broken, and often are. But the idea of negotiating peace agreements has, over time, been built on a more nuanced view that there can be diverse material and non-material issues at stake in a conflict. So, to produce a sustainable peace agreement, parties need to recognise the range of issues on the table, reach mutual understandings concerning those issues where possible, and agree to address any ongoing differences peacefully.

Such an approach underwrote the Good Friday Agreement, which has contributed to a lasting peace in Northern Ireland. A transactional “Good Friday deal” may not have done the same.

Third-party mediators from the international community can play key roles in facilitating negotiations. As such, involvement of the US and wider global community in supporting peace processes in Ukraine, Gaza and beyond should be welcomed.

But the aim of external parties should be to organise and take part in negotiations that go beyond dividing material resources according to current distributions of power. A wider set of interests, issues and rights should be incorporated into the language and practice of peace negotiations so that comprehensive, just and sustainable peace agreements can be reached between parties and communities that have been divided by war.

Changing the way we speak about peace may seem merely symbolic – but it’s actually critical. Reframing discourse away from “deals” towards “agreements” could help align the language and practices of peacemaking with the realities on the ground. This in turn could facilitate the negotiation of just – and sustainable – peace settlements in complex contexts such as Ukraine and Gaza.

![]()

John Gledhill does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.