Detta inlägg post publicerades ursprungligen på denna sida this site ;

Date:

Author: Anthony Macris, Professor of Creative Writing, University of Technology Sydney

Original article: https://theconversation.com/punishment-in-search-of-a-crime-franz-kafkas-the-trial-at-100-247230

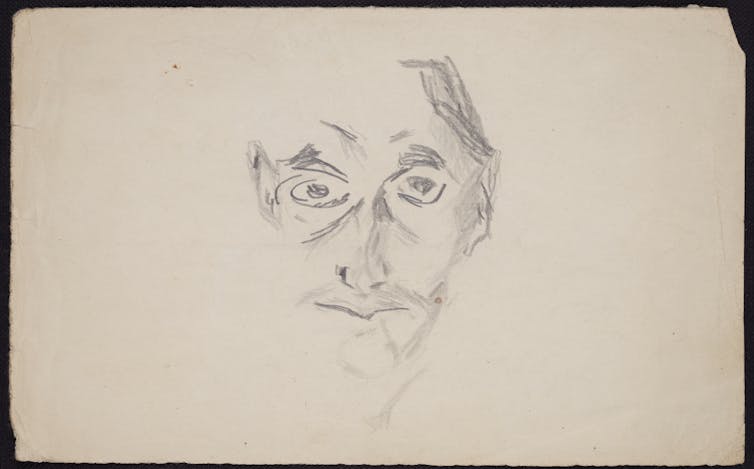

“A book,” a 20-year-old Franz Kafka wrote to his friend Oskar Pollack in 1904, “must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us.” It is a quintessential Kafka image. I see an ice-axe, the sharpened point of its curved metal head shattering a vast plane of ice into hairline curves that ramify in all directions.

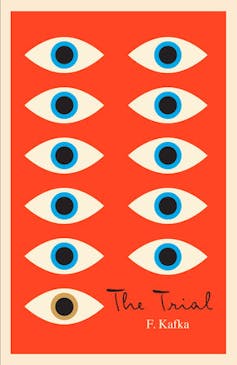

This kind of blow, this shattering of the surface of the world, produced one the greatest novels ever written, The Trial, and introduced to literature one of its most compelling characters, Joseph K., a senior bank clerk doomed to a tragic fate.

In its opening sentences, the novel’s premise is established with lightning speed. One workday morning, K. wakes up to find two strange men in his bedroom, who inexplicably place him under arrest. Later, he is sentenced to death for a crime he knows nothing about by a judge he never sees.

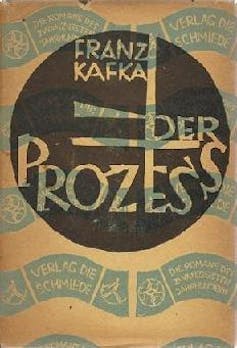

Public domain

One hundred years after its publication on April 26, 1925, the blow of that axe is still being felt. The feeling it engenders is crystallised in a single adjective: “Kafkaesque”. It is a modifier that has become as famous as Kafka himself.

The Trial was written over the period 1914-15, when Kafka was in his early 30s. Like his two other novels – Amerika (alternatively known as The Man Who Disappeared) and The Castle – it was never finished. Kafka was a perfectionist who, as his diaries reveal, struggled with his artistic self-worth. He published little in his lifetime: two short story collections, some story extracts, and his novella The Metamorphosis, which went largely unnoticed.

We would not even have the novels if not for the intervention of Kafka’a close friend and literary executor Max Brod. Thankfully, Brod ignored Kafka’s instructions to destroy his manuscripts after his untimely death from tuberculosis at the age of 40 in 1924. The Trial was the first of the novels to be published posthumously, with the others appearing soon after.

The Kafkaesque

Fellow Czech writer Milan Kundera, whose youth was shaped by Stalinist communism, characterised the Kafkaesque as a state of powerlessness when trapped inside a boundless labyrinth. He also saw in it an inversion of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment. No longer is a crime met with a punishment; rather, the punishment goes in search of a crime.

For poststructuralist philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Kafka pioneered the notion of a “neo-bureaucracy” of “corridors, of segments, a string of offices” that marked “the transition from the old archaic imperial bureaucracy to modern bureaucracy”. They found Kafka’s world view so powerful they incorporated it into their influential theories of capitalism and schizophrenia.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Joseph K.’s grisly fate plays out in an anonymised city, most likely derived from Kafka’s home of Prague. The city’s Austro-Hungarian ornamentation is stripped to bone, leaving only a kind of proto-brutalist substratum. It’s a powerful setting. Has a writer ever generated so much strangeness and awe, so much psychological power, with such basic materials?

Much of the novel’s action occurs in genteel boarding houses, bank offices, run down tenements, a dilapidated artist’s studio, a quarry. Its potentially grandest setting, a cathedral, is rendered in dark, blurry tones.

From these modest elements, Kafka builds vast panoramas, sweeping landscapes, all in the theatre of the mind. It is a phantasmagoria assembled from the world of concrete things – Kafka is nothing if not a writer of specificity – yet it seems to be moulded from some kind of dark matter, the very stuff of consciousness: sensory data that is as close to mind as the senses can be, but which dissolves in instant, only to reconfigure as a new room, a new office, a new studio.

In these rooms, a varied cast of characters orbit the hapless K., each exerting an influence, both direct and indirect, on his fate. In K.’s personal world, there are his landlady, his love interests, bank colleagues, his uncle and guardian. In the world of the trial, which increasingly bleeds into every aspect of his existence, there are the petty officials, his lawyer, the painter, the priest.

In his encounters with them K. shows the many sides of his personality. He is by turns polite and dismissive, decorous and licentious, driven by a burning sense of injustice, yet prone to periods of lassitude.

What he is not is paranoid. The theme of paranoia is central in The Trial (and in the Kafkaesque itself), but it exists at a much more pervasive level than that of the mere individual. To see K. as paranoid limits our understanding of what Kafka is trying to achieve. In fact, K.’s response to his arrest is anything but paranoid. He displays a misplaced confidence that everything will turn out for the best. Instead of fearing the invisible forces arrayed against him, he is often combative and sardonic, cruelling his chances of acquittal at every turn.

In Kafka’s Weltanschauung, the world itself has become irrational, arbitrary and malevolent: a machine for the production of paranoia. K.’s stance is that of someone who is trying to remain sane in a world gone mad. One way he does this is by refusing to internalise the values of a perverted system. He is innocent, as far as he is concerned, and never passes up an opportunity to declare it. His naivety in the face of the court is his purity.

There is no court more perverse than the one found in The Trial. It is ingeniously staged, revealed to us only in glimpses. We first physically encounter one of its offices on the top floor of a working-class tenement building. A small door is opened at the back of a cramped, grubby flat and behind it, where we least expect, is a large, crowded room, buzzing with the activity of the hearings in session.

This is where K. attends his first and only hearing. Like the tenement building, the room is dirty and dilapidated. The hearing is a farce. The magistrate mistakes K. for a house painter. Because of his strenuous proclamations of innocence, K.’s hearing never gets off the ground.

Later, K. visits this room again when the court is out of session and takes the opportunity to nose around. Examining the magistrate’s reference books, he sees that one is full of clumsy pornographic drawings. Another is titled “What Greta Suffered from her Husband Franz”.

The Trial is full of such absurd humour, trompe l’oeil effects, and manipulations of scale. It also contains touches of what would come to be called surrealism. For example, when the amorous wife of the court attendant shows K. her hand as she tries to woo him, she reveals that two of her fingers are joined by an overgrown web of skin.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Though we see little of the court, we experience it everywhere through its proxies and their endless discussions on how it operates. K.s lawyer, the bedridden Herr Huld, describes a network of judges that “mounted endlessly, so that not even adepts could survey the hierarchy as a whole”.

In lengthy monologues, Huld explains the court’s endlessly deferred processes. Reports can be drafted, only to have their completion delayed for any number of reasons. Even if they are submitted, they usually end up circulating up and down the system in great recursive loops with no definitive outcome.

Titorelli, the court painter to whom K. is sent to progress his case (even though he has no official status), describes the behind-the-scenes operations of the court. There is the lobbying of judges that must be pursued in order to influence the outcome. Verdicts, Titorelli points out, can only end in a pronouncement of guilt, but not necessarily death.

K.’s best option, he advises, is to admit his guilt, but to choose a category where final sentencing is deferred, perhaps forever, perhaps not: there are no guarantees. His case could be reactivated at any time, resulting in the gravest of consequences, or perhaps never – who could tell?

How is an increasingly dispirited K. meant to negotiate such a menacing world, accept its insane norms? The priest in the penultimate chapter proffers an answer. K. should not “accept everything as true, only as necessary”.

K. responds: “A melancholy conclusion […] It turns lying into a universal principle.”

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Dialectic of unenlightenment

Part of the dramatic brilliance of The Trial is the way Kafka brings all of this deferral and recursion to an abrupt halt in the form of the ultimate act of closure: death.

In its combination of menace and comedy, K.’s execution is arguably one of the most chilling chapters in all of literature. It has the hallmarks of a sacrifice, but one that has no point, no reason or explanation. On the eve of his 31st birthday, one year after his arrest, K.’s executioners, taciturn men dressed in black, appear in his room. They frogmarch him out of town to a disused quarry, where they lay him out on a stone and, under the moonlight, plunge a knife through his heart.

Everything about the execution is primeval, ritualistic, atavistic. What is the nature of this nightmare world, where such an arbitrary execution can take place? It is not only a world where lying is the norm, a world where reason has lost its way: it is much worse than that. This nightmare world consciously works at every point against reason, against the Enlightenment belief that reason leads us to a truth.

Any possibility that humanity is continuously improving, that each successive generation draws closer to truth, is repudiated. Within the ideals of the Enlightenment, The Trial suggests, there lurks the dark glow of the irrational, the persistence of a power that loves nothing but itself, a power that will destroy capriciously and without explanation.

This is illustrated in the novel’s final scene. K. finally acquiesces to his fate and dies, to use his own words, “like a dog”. With this thrust of the dagger, Kafka sets in motion a reverse teleology, a dialectic of unenlightenment, one where we fall backwards into a corrupt moral order we believed we had transcended, at least in principle.

“I think we ought to read only the kind of books that wound and stab us,” the young Kafka wrote in his letter to Oskar Pollak. “If the book we are reading doesn’t wake us up with a blow on the head, what are we reading it for?”

Kafka is still waking us up, 100 years after the publication of The Trial. Whenever power goes awry, serving sinister forces that enact the law according to a perverse set of whims it calls justice, we know we are in the world of the Kafkaesque. Yes, Kafka’s worldview, for all its comedy, is bleak and dark. But it sheds a unique light: the kind of illumination of human nature that is essential, revealing aspects that, once seen, cannot be unseen. Without it, we would not only be asleep; we would also be blind.

![]()

Anthony Macris does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.