Detta inlägg post publicerades ursprungligen på denna sida this site ;

Date:

Author: Paul Whiteley, Professor, Department of Government, University of Essex

Original article: https://theconversation.com/mrp-poll-puts-reform-ahead-of-labour-and-the-tories-heres-why-the-finding-should-be-treated-with-caution-255296

Thinktank More in Common recently published an MRP (multi-level regression with post-stratification) poll which appears to show that if there was a general election in the near future, Reform would win 180 seats. According to the analysis, Labour and the Conservatives would win 165 seats each and the Liberal Democrats 67. The modelling suggests that Labour could lose 246 seats including 153 to Reform and 64 to the Conservatives.

More in Common claims that this is not a prediction of the result of the next election, writing: “With four and a half years before the next general election must be called this model is unlikely to represent anything close to the ultimate result and should not be seen as a projection of the election.” Despite this health warning, the poll has spooked some political journalists.

It is worth remembering how MRP surveys work. Agencies ask a very large sample of electors about their voting intentions – enough to have an average sample size of about 25 respondents in each of the 632 constituencies in Great Britain. This allows them to use data from the census and other sources to identify constituency characteristics which influence individual voting decisions, such as social class, age and income.

These are then combined with the survey data to get a prediction of how people are likely to vote in each constituency. This can then be used to predict seats won or lost by the parties in the election.

More in Common did well in forecasting the results of the 2024 general election. Just prior to polling day it conducted a regular poll alongside an MRP poll, and it turned out that the regular one was more accurate in predicting the result than the MRP poll.

A general problem with MRP polls

This appears to be a general problem when MRP poll estimates are compared with traditional polls. The difficulty is that the MRP estimates can vary widely depending on the details of the modelling. In addition, the conditions required for MRP to work well are not always met by practitioners.

To illustrate this last point, the models rely on demographic variables such as social class, gender and age at the constituency level to work well. If the relationship between these variables and constituency voting is strong, this will help to explain individual voting behaviour identified in the survey.

But if the relationships are weak, the demographics will not be much help. This is a problem because the relationship between demographics, particularly social class, and voting, has been weakening over time.

Social class and voting

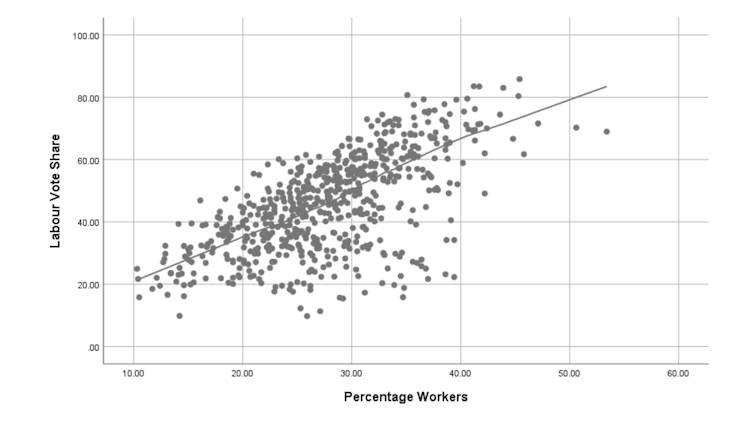

The chart below shows the relationship between the size of the working class in constituencies across Britain and voting Labour in the 1964 general election. Each dot represents a constituency, and social class is measured in the 1961 census by occupational status with, for example, labourers defined as working class and doctors as middle class.

Labour leader, Harold Wilson, did a good job in mobilising working class voters in constituencies across Britain and went on to win in 1964. This was possible because of the strong positive relationship between the size of the working class and Labour voting apparent in the chart.

Working class electors and Labour votes, 1964:

P Whiteley, CC BY-ND

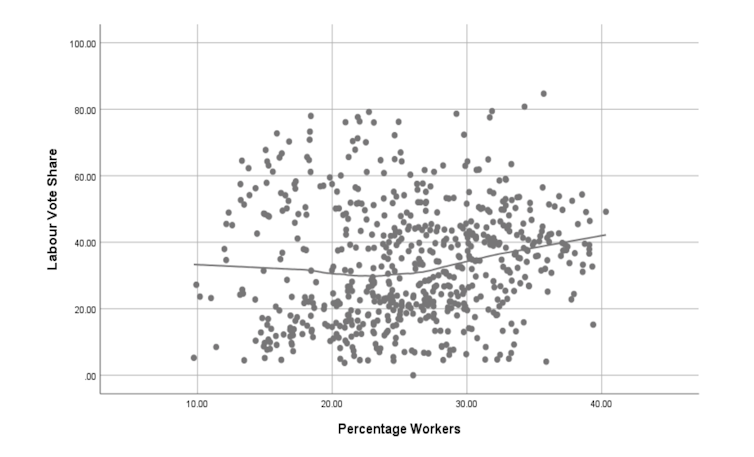

Fast forward 55 years to the 2019 election and we see something completely different. By then the relationship between the size of the working class and Labour voting at the constituency level had largely disappeared.

This means that in the 1964 election, constituency information about class would have been very helpful in conducting an MRP survey. However, by 2019 it would have been of little use.

To understand voting behaviour, we need a clear theory of why people vote the way they do. In 1967, political sociologist Peter Pulzer wrote: “In British party politics, social class is everything, all else is embellishment and detail.” This is no longer true.

Working class electors and Labour votes, 2019:

P Whiteley, CC BY-ND

Now we are in an age of performance politics with parties judged on their ability to deliver the things that people want, like economic growth, low inflation and efficient public services. Class ties are increasingly irrelevant to this because electors will change their votes if they think another party will do a better job.

In relation to the upcoming local elections, this means that potholes are likely to be more important to voters than their social class identities. If the 2021 census had asked about attitudes to potholes that would be very useful in constructing an MRP, but unfortunately it did not.

This means that the constituency data used in MRP polling often comes from other surveys rather than from the census, which has the advantage of interviewing everyone. More in Common explains that it used post-election polling to approximate the demographics needed at the constituency level, which of course is an additional source of potential error.

MRPs are now a feature of the polling landscape, and they are useful in the run-up to a general election. But it’s questionable whether it is worth spending a lot of money to acquire the large samples needed to make them work when the election is years into the future.

![]()

Paul Whiteley has received funding from the British Academy and the ESRC.