Detta inlägg post publicerades ursprungligen på denna sida this site ;

Date:

Author: Diego Muro, Senior Lecturer in International Relations, University of St Andrews

Original article: https://theconversation.com/what-weve-learnt-about-lone-actor-terrorism-over-the-years-could-help-us-prevent-future-attacks-254137

Politically motivated attacks, carried out by lone individuals lacking direct affiliation with any terrorist group, have become more common in Europe during the last few decades.

One of the most common and devastating forms of lone-actor violence involves driving into crowds. In 2016, Mohamed Lahouaiej-Bouhlel used this method to kill 86 people in Nice. In 2011, Anders Breivik detonated a bomb in central Oslo before carrying out a mass shooting on the island of Utøya, leaving 77 dead. Not all lone-actor attacks are as deadly or indiscriminate as these. Some target specific people, as seen in the assassinations of German politician Walter Lübcke in 2019 and British MP David Amess in 2021.

Lone-actor terrorism – also known as lone-wolf terrorism – poses a unique challenge for European states. Traditional counterterrorism tools designed for organised groups like al-Qaeda, Islamic State, or Eta are far less effective against people acting alone. While lone-actor plots are typically less complex, they can still cause significant harm.

We’ve also seen that lone-actor attacks can trigger far-reaching ripple effects. The resulting public outrage can intensify debates on contentious issues like immigration, and ultimately boost support for extremist parties.

Copycat or reactionary attacks are another consequence of lone-actor terrorism. A striking example is the mass shootings carried out by Brenton Tarrant in New Zealand in 2019. He cited the actions of Breivik and others as direct inspiration. According to Tarrant’s own manifesto, a key trigger for his radicalisation was the 2017 Islamist attack in Stockholm, where Rakhmat Akilov, an asylum seeker from Uzbekistan, drove a truck into a crowd, killing five people, including an 11-year-old child.

Why lone-actor attacks are so difficult to prevent

Because lone actors operate independently and rarely communicate their intentions, their identities often remain unknown until after an attack. Their goals and ideologies are frequently ambiguous, making it hard to predict behaviour or select likely targets. Even correctly identifying an incident as lone-actor terrorism can be challenging.

The case of Axel Rudakubana illustrates this difficulty. Rudakubana killed three young girls in Southport, northern England, in 2024 after breaking into their Taylor Swift-themed dance workshop. Despite the discovery of an Al-Qaeda training manual in his possession, prosecutors found no substantial evidence of political motivation and labelled the incident a “mass killing” rather than terrorism.

It is very difficult – if not impossible – to determine the exact number of lone-actor terrorist attacks that have taken place in Europe with certainty. The absence of a universally accepted definition of terrorism is part of the problem. It’s also possible that acts of mass violence are being classified as terrorism when they are actually ideologically neutral. Equally, it can be difficult to determine whether an actor truly acted alone, especially in an age of internet radicalisation.

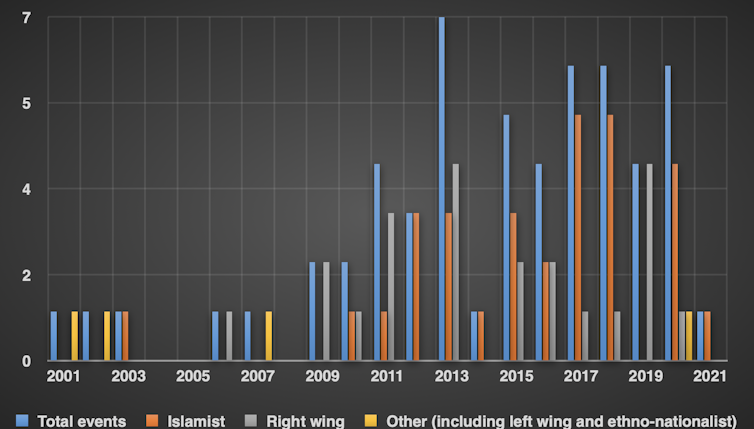

What is clear is that independent terrorist attacks became more frequent in the early 2010s. By 2013, such incidents spiked, with Europe seeing six to seven Islamist and far-right attacks per year (up from fewer than one annually before 2010). These figures refer strictly to cases where perpetrators acted independently, excluding those with evidence of external support. For example, Anis Amri’s 2016 truck attack in Berlin and Taimour al-Abdaly’s 2010 suicide attempt in Stockholm were initially seen as lone-actor events, but later investigations revealed ties to Islamist cells.

Lone-actor terrorism appears less common among far-left and ethno-nationalist groups, though exceptions do exist.

Lone-actor terrorist attacks in Europe

D muro, O Craciunas, CC BY-ND

This shift towards lone-actor attacks is likely a result of evolving counterterrorism strategies implemented after major attacks like the 2004 Madrid train bombings and the 2005 London bombings. It became harder to carry out large-scale plots so groups like Al-Qaeda and later Islamic State switched to encouraging or organising attacks by loosely affiliated individuals acting independently but on their behalf.

The struggle between terrorist groups and governments is one of constant adaptation. By 2018, Europol data indicated that all the Islamist attacks that had been seen through to completion in Europe during that year had been carried out by lone actors.

Lone-actor attacks have an even longer history within far-right terrorism. The term “lone-wolf terrorist” was first popularised in American white supremacist propaganda in the early 1990s – well before the more neutral term “lone-actor terrorist” was adopted by researchers. As counterterrorism efforts increasingly targeted white supremacist groups, many within the movement came to see independent action as the most effective way to evade detection and maintain operational secrecy.

Addressing the threat

Fortunately, we now understand more about lone-actor crimes. We’ve come to understand that these attacks stem from complex psychological and environmental factors.

While perpetrators shouldn’t be dismissed as simply “crazy,” mental health can play a role in radicalisation, especially when combined with personal grievances, failed aspirations, and perceived injustices. Influences from family, peers and online spaces also shape this process. While no two radicalisation pathways are identical, certain patterns can be observed – and recognising them early may help reduce the threat.

The idea of “self-radicalisation” also merits caution. Lone actors rarely radicalise in isolation; their manifestos often echo broader ideological themes, shaped by conspiracy theories or charismatic figures. These actors often assign symbolic meaning to their actions. Raising awareness of the impact of violent public discourse is key – though this must be done without infringing on free speech. History shows that providing “pressure valves” for controversial ideas is more constructive than censorship.

Lone-actor attacks are, in part, difficult to prevent precisely because they are not a systemic threat in the way that coordinated, group-based terrorism can be. Its danger lies in isolated bursts of violence rather than in sustained campaigns. But there are patterns worth following that could help prevent future incidents.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.