Detta inlägg post publicerades ursprungligen på denna sida this site ;

Date:

Author: Erika K. Smith, Associate Lecturer, School of Social Sciences, Western Sydney University

Original article: https://theconversation.com/the-phrase-fuzzy-wuzzy-angels-is-far-from-affectionate-it-reflects-500-years-of-racism-253953

This article contains mention of racist terms in historical context.

Every Anzac Day, Australians are presented with narratives that re-inscribe particular versions of our national story.

One such narrative persistently claims “fuzzy wuzzy angel” was used as an “affectionate” name for local stretcher-bearers of sick and wounded Australian soldiers during the New Guinea campaign of 1942 to 1945.

Papua New Guineans called Australian soldiers masta (master), taubada (big man), and bos (boss). Australian soldiers called Papua New Guinean people by racist phrases including boong, nigger, kanaka, coon, boi, boy and wog.

Our new research shows that, far from being “affectionate”, the phrase fuzzy wuzzy angel is best understood in this context – and in the context of 500 years of anti-Black racism.

These other offensive terms used by soldiers are largely gone from the public domain, yet fuzzy wuzzy angel persists. We decided to explore this apparently acceptable form of contemporary racism.

Power relations across the centuries

In 1526 the Portuguese explorer Jorge de Menezes named islands in the west of what is now West Papua Ilhas dos Papuas.

“Papuas” was a borrowed word by the Portuguese of Malay/Indonesian origin, meaning “frizzled” or “curly-haired”. The islands were therefore known as the “islands of the frizzy-haired people”.

In 1545, the Spanish explorer Yñigo Ortiz de Retez named the east mainland Nueva Guinea (New Guinea). As historian J.H.F. Sollewijn Gelpke describes it, Ortiz de Retez saw a physical resemblance to the “frizzy haired inhabitants […] of the Guinea Coast in West Africa”.

The first usage we found of the phrase fuzzy wuzzy angels relating to the New Guinea campaign was in an article in the Sydney’s The Daily Mirror in 1942. A war correspondent reported troops along the Track were reciting a “catchy verse with a swing in it”.

The “catchy verse” appears to borrow directly from the 1892 poem Fuzzy Wuzzy, by English writer Rudyard Kipling. Kipling borrowed the phrase from how British soldiers referred to the Beja warriors of north-east Africa during the Mahdist (Anglo–Sudan) War of 1881–99.

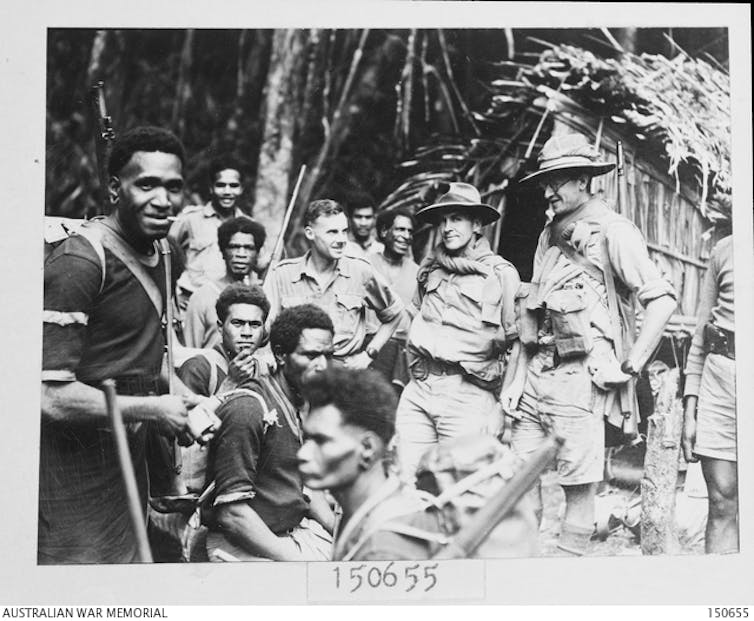

Shortly after the poem was published in The Daily Mirror, the image of the “fuzzy wuzzy angel” was immortalised in a photograph. George Silk’s image shows Raphael Oimbari (Hanau village, Oro Province) walking with injured Australian soldier Private George “Dick” Whittington (2/10th Battalion) on Christmas Day, 1942.

While Whittington was identified as the injured soldier, it wasn’t until the 1970s that Oimbari was identified and named as the Papua New Guinean guide.

The cultural journey of Kipling’s poem in Africa to Australian infantry on the Kokoda follows the same route as Spanish and Portuguese sailors from African Guinea to Papua New Guinea.

This focus on frizzy or fuzzy hair homogenised Blackness under the colonial gaze.

Continuing racial relations

Far from being just stretcher bearers, local people during the Kokoda Campaign were often forced to support the Australian war effort in roles including cooks, cleaners, labourers, construction workers, farm hands and carriers of ammunition.

These roles have also disappeared from our national narrative, along with the more racist forms of address.

In place of historically accurate accounts is a distilled national narrative: iconic stretcher bearers “affectionately” known as fuzzy wuzzy angels.

Australian War Memorial

There was little interest in the Australian war story in Papua New Guinea and the Kokoda Track between the end of the war and the early 1990s. Then, in 1992, Prime Minister Paul Keating kissed the foot of the Kokoda Memorial.

Attention by subsequent prime ministers and an increased number of books and films propelled the Kokoda Track into mainstream Australian consciousness.

Prime Minister John Howard made the “affectionate” usage claim in a speech to Papua New Guinea Prime Minister Bill Skate in 1998.

Papua New Guinean scholar Regis Tove Stella wrote in 2007 that fuzzy wuzzy angel is “belittling and consistent with the discourse of paternalism that largely characterised colonial administrative policy”.

Yet we continue to see Indigenous perspectives erased in favour of the “affectionate” account.

When Malcolm Turnbull laid a 75th anniversary wreath in April 2017, the Australian Associated Press included this explanatory paragraph:

Local Papua New Guinean men, dubbed affectionately the ‘Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels’, assisted and escorted wounded and injured Australian soldiers along the trail.

In 2024, “affectionate” was reinscribed by Peter Dutton in an address to parliament to honour Papua New Guinea Prime Minister James Marape.

500 years of a racist phrase

Australia’s northernmost island, Saibai Island of Zenadh Kes/Torres Strait Islands, is less than 4 kilometres from Papua New Guinea – yet most Australians know little about our closest neighbours.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Papua New Guinea’s independence from Australia, mobilised by the Whitlam government, some 25 years behind the post-war decolonisation movement.

Yet official decolonisation has not stopped Australians from insisting that it is affectionate – and, by implication, not racist – to use colonial naming practices that date back some 500 years.

This article draws on research conducted during Erika K. Smith’s doctoral candidature which was financially supported by an Australian Postgraduate Award and a Western Sydney University Postgraduate Research Scholarship.

Ingrid Matthews does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.