Detta inlägg post publicerades ursprungligen på denna sida this site ;

Date:

Author: Mia Martin Hobbs, Research Fellow, War and Oral History, Deakin University

Original article: https://theconversation.com/friday-essay-war-has-made-me-a-pacifist-why-are-we-so-reluctant-to-acknowledge-australias-anti-war-veterans-253530

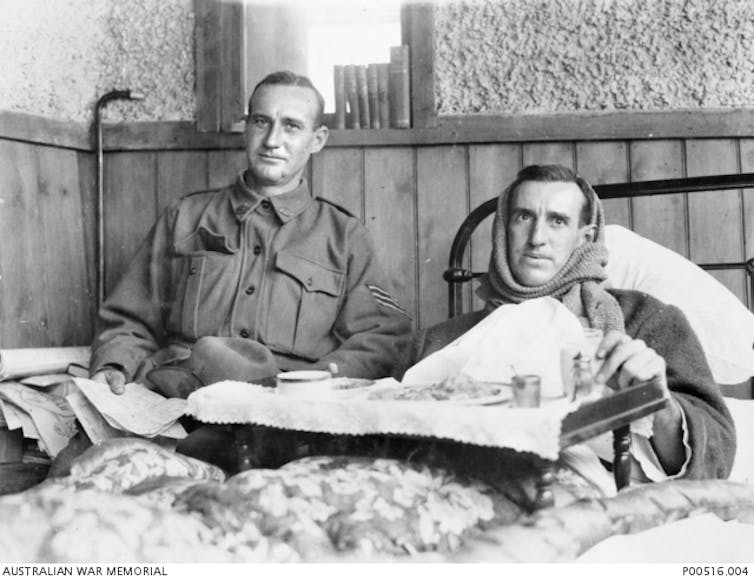

“I have seen enough of the horrors of war, and want peace. War has made me a socialist and a pacifist,” announced Gallipoli veteran and Victoria Cross winner, Hugo Throssell, on Peace Day in 1919.

Throssell was shot in the neck on Hill 60 at Gallipoli in 1915 and nearly died from surgical complications. He returned to the frontlines in Egypt in 1917. There, he was reunited with – then lost – his brother Eric, who was killed in action.

Throssell wrote to his wife, Katharine Susannah Prichard, of searching for Eric in battle in vain, “crawling across the battlefield, still under enemy fire”. After the war, he reflected on the “colossal profits” made in war, concluding that while it was possible for men “to profit by war, we will always have war” and advocating for society’s reorganisation “for the wellbeing of the community as a whole”.

Australian War Memorial

Most war historians today would agree with Throssell’s assessment of the first world war: an imperialist war and a wasteful tragedy. Yet despite regular echoes of “Lest We Forget” on Anzac Day, the views of soldiers and veterans who disagree with Australia’s involvement in wars, both past and present, are rarely heard.

It has become rather fashionable to refer to soldiers’ stories as “forgotten”, or “hidden”. The “forgotten” lament – often associated with the most widely studied topic in Australian history – has become something of a collective joke among war historians. But Throssell’s service was not forgotten. He was honoured in Anzac Day events in Perth throughout the 1920s and 1930s, and buried with full military honours after his suicide in 1933. Obituaries hailed his war record.

However, Throssell’s anti-war views, derived from his firsthand knowledge of war and its consequences, were largely ignored.

This pattern repeats across Australian history, from the first world war to the War on Terror. In every war, there have been a number of soldiers and veterans who turned against it, Some became pacifists, while others acknowledged the necessity of war in rare instances. They drew on their war experience to caution restraint, urging war-makers to reflect on Australian values and interests before committing Australian lives overseas.

Yet these radical veterans’ voices are excluded from veterans’ organisations, diminished in the media and ignored by cultural institutions. These critical perspectives could nuance Australia’s understanding of its war history and inform its involvement in future wars. But they have been siloed off.

I am one of a group of historians working on the Challenging Anzac project, exploring the stories and experiences of service members and veterans across history who contradict Australia’s war mythology. Our research reveals a longstanding reluctance in Australia to acknowledge and honour the anti-war feeling among our soldiers and veterans.

War an “abbatoir”

Many Australians joined up for the first world war with great enthusiasm: eager for adventure, to prove their manhood, and serve their King and country.

Edward “Ted” Ryan, from Broken Hill, New South Wales, enlisted in September 1915, swearing an oath to “serve our Sovereign Lord the King” and “resist his Majesty’s enemies.” Ryan fought with the 51st Battalion on the Western Front and was severely and repeatedly injured at the Somme and at Pozèries in 1916.

Evacuated to England, Ryan was ordered to return to service at Perham Down, a Hardening and Drafting depot where wounded Australian soldiers retrained – or “hardened” – for redeployment. At Perham Down, Ryan addressed a letter, condemning war, to Britain’s leading anti-war politician, Ramsay MacDonald, records historian Doug Newton.

Contradicting the British press portrayal of Australian soldiers as “bright & cheering, hooraying” for war, Ryan said they despised what they referred to as “the Abattoirs”. They were frightened and sick of war:

I have not spoken to one man who wants to go back to the firing-line again. Every man I have spoken to is absolutely sick of the whole business. I have just been speaking to two Anzacs who said they would rather be shot than face another bombardment.

Ryan ended his letter by urging MacDonald to “do everything possible in your power to bring about a Peace and save this slaughter of human lives”. His was one of many letters MacDonald received from anti-war soldiers across the Imperial forces, who had become “revolutionary” because of the war.

Ryan’s later war years saw him repeatedly go absent without leave, a pattern Newton found was “notorious” among Australian soldiers who argued they had volunteered for war, so were entitled not to return to it.

Other soldiers made more symbolic gestures of opposition. Many Australians with ancestors who fought in the first world war may have heard stories of soldiers shedding uniforms or discarding medals upon demobilisation, to rid themselves of reminders of war.

State Library of Victoria

Novelist Martin Boyd enlisted for the war after hearing some of his friends had died at Gallipoli. He drew on his war experience to write a novel, When Blackbirds Sing (1962). Protagonist Dominic goes to war to fulfil his “purpose” of killing his enemy, but becomes haunted by the humanity in the eyes of a young German soldier he shot. After being bayoneted himself, Dominic writes to his benefactor, “I have taken off my uniform and shall not wear it again”. He explores the immorality of the war, arguing he would fight for his friends and home

if anyone threatened them. But they are not threatened, except by our own government.

When he returns to Australia, Dominic receives his war medals and throws them in a dam.

Socialists and communists in the ranks

Despite the horrors of war, many Australians found a sense of community with their fellow soldiers. Militaries foster a deep sense of belonging, which veterans describe as feeling like being “links in a chain”, utterly dependent on one another for survival. In the 1980s, historian Alistair Thomson conducted an oral history project with “radical diggers” of the first world war.

He found the concept of “mateship” – a core component of the Anzac legend – in fact stemmed from the socialist tendencies and solidarity among working-class soldiers against their military leaders, who treated them like pawns on a chessboard.

Fred Farrall, for instance, who fought in Egypt and then on the Western Front, described his fellow soldiers pelting visiting generals with fistfuls of dirt after losing most of their battalion.

Darge Photographic Company/Australian War Memorial

The mateship of the military attracted many returned soldiers to the trade union movement, which offered a similar solidarity. In Western Australia, historians found returned soldiers among the Lumpers, or dockers, who refused to break strikes in Fremantle in 1917–1919. They were hard to restrain, after a rumour circulated that a Lumper who had been bayoneted by police was a returned soldier. The rumour turned out to be false.

The mutual support of the union movement was a solace to those veterans who struggled to recover from war wounds. Allan Whittaker was 23 when he enlisted in 1914, deploying to Gallipoli with the First Battalion. Shot in the ankle and invalided out, or medically evacuated, Whittacker was hailed as a wounded hero on return to Australia.

But he struggled to survive on his war pension while his wounds healed. He took work on the Melbourne wharf, joining the wharfies’ strike in 1928. He was shot in the neck by police on the picket line and died slowly, buried by his union comrades.

Yet since the war itself, Australian institutions have downplayed and disconnected veterans’ radicalism from their war service.

Horace Ratliff, a labourer from Gundagai, fought in Gallipoli and then on the Western Front. After the war, he became a communist, writing literature for the Party and holding underground meetings. During the second world war, he was interned for communist activity and held a hunger strike.

Australian War Memorial

Of over 700 archived newspaper articles reporting on his imprisonment, only 32 mention he “happened to be a returned soldier with a good war record”.

The erasure of Ratliff’s military service from reporting on his communist activity suggests a deeper discomfort in Australia with the idea former soldiers might become radical leftists.

Alienated from the RSL

In fact, since the war had ended, authorities had worked to neutralise the radical potential of returned soldiers.

Fearful of the disruptive threat of a large, battle-hardened population, Australian authorities and unions granted employment preference to returned soldiers. Throughout the Great Depression of 1929–1939, they prioritised them above other workers.

This policy was closely monitored by the Returned Sailors and Soldiers Imperial League of Australia (now known as Returned and Services League of Australia, or RSL), which had emerged as the dominant veterans’ organisation in the immediate aftermath of war.

The generosity of Australia’s repatriation programs for veterans, staunchly advocated for by the RSL, initially engendered widespread support from former soldiers.

By 1919, the RSL represented nearly half of all veterans. Yet membership of the RSL plummeted throughout the 1920s, when it represented less than 10% of all Australian veterans. During the Great Depression, it recovered membership, to around 30%.

Having gained some of the most generous repatriation entitlements in the world, many Australian veterans saw no need to remain in a veteran organisation. They “preferred to put the war behind them”.

The remaining members were the hardliners, who positioned themselves as the stewards of the Anzac legend. They entrenched a deeply conservative ideological position in the peak body representing veterans in Australia. This, in turn, alienated more veterans.

Sid Norris, who fought on the Western Front and suffered both a gunshot wound and shrapnel to the face, attended one local meeting of the RSL, but left after “heckling a clergyman preaching King and Country”, he explained. While the RSL has claimed to speak for veterans, it has never represented the voices of the majority of them.

For example, the RSL believed their soldier status was a privileged position in Australian society – and should come before class solidarity, as historian Martin Crotty has argued. This view led to poorer soldiers being implicitly excluded from the veterans’ organisation.

Stan D’Altera served in the 23rd Battalion in Suez and Gallipoli. He joined the RSL after his service, believing it would be an organisation for servicemen “to battle for better conditions”. D’Altera told Alistair Thomson he resigned his local branch in Footscray when it refused to support those who could not afford membership in the Depression. He later became an organiser for the soldiers’ section of the Unemployed Association.

Radical veterans were also formally excluded from the RSL. Fred Paterson saw service in France and organised strikes among the soldiers on the Western Front, before returning to a life of politics. He was at the forefront of the Communist Party in Queensland and was elected to the seat of Bowen in 1944.

A regular on the picket line, he intervened in a police assault on a demonstrator in Brisbane in 1948 – and was hit from behind by another police officer. While Paterson recovered, the Queensland branch of the RSL expelled him. This action alienated many the organisation claimed to represent: veterans including Ern Morton resigned from the RSL in response.

Radical veterans who resigned were “regarded as traitors” and became targets for “venomous intimidation” from members of the RSL, noted Thomson.

The attrition of radical members from the RSL is a recurring factor in the erasure of radical histories of veterans. As Paterson himself argued, if radicals in the RSL resigned “they would be playing into the hands of the reactionary leaders who were striving to turn the League into an anti-working class organisation”.

This is in fact what happened. Thomson argues:

The RSL successfully appropriated the definition of “the digger” so that “radical digger” had become a contradiction in terms, and many left-wing veterans shed their identity as returned servicemen.

Fred Farrall, for instance, challenged the increasingly jingoistic messaging around Anzac Day, distributing pacifist leaflets on the day and wearing his service badge at May Day events. He told Thomson he had come to identify as a “soldier of the labor movement” instead.

Opposition to fascism

The schism within the returned soldier community reflected the broader political conflicts of the interwar years.

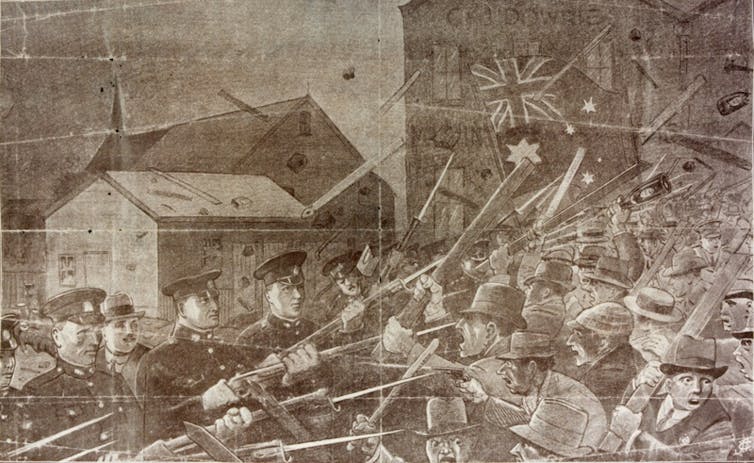

First world war veterans populated anti-communist movements and fascist paramilitary groups, for example, in the Red Flag Riots in Brisbane in 1919 and in the New Guard and White Army in the 1930s. Yet veterans were also among the socialists and communists who fought against them.

In the Red Flag Riots in Brisbane in 1918 and 1919, Gallipoli veteran George “Gunner” Taylour was physically attacked by members of the RSL after giving a speech about peace and revolution.

Queensland Police Museum/Ehvive, CC BY

Taylour later led “a handful of radical returned soldiers” in a protest outside Trades Hall. Charged with displaying the banned red flag, he was sentenced to six months at Boggo Road Gaol.

In the 1930s, historian Andrew Moore located British Army migrants among the “battle-hardened revolutionaries” of the Workers Defence Corps. A paramilitary initiative of the Communist Party that emerged in the 1920s, it operated in opposition to the “Fascist New Guard Organisations”.

A much smaller, largely intellectual group, the Ex-Servicemen’s Defence Corps, counted James Normington Rawling, a veteran and life-long anti-war organiser, among their number.

Returned soldiers’ opposition to fascism was not contained to conflict within Australia. Between 1936 and 1939, 60 Australians are known to have travelled to Spain, in the International Brigades Against Fascism. At least five of them were returned servicemen, who had “returned to a life of union and political agitation”.

Brigade volunteers linked their efforts in Spain to Australia’s experience in the first world war, found historian Amira Inglis. They referenced Gallipoli and the Anzac legend in eulogies and commemorations.

Several International Brigade veterans went on to serve in the second world war, to continue their anti-fascist effort. Jim McNeil enlisted at the outbreak of war, just nine months after returning wounded from Spain. He and others like him “just hated fascism and wanted to fight it”, he explained.

These stories show not all radical veterans became pacifists. Some recognised the necessity of countering the extreme threat fascism posed to Australia, at home and abroad.

Conscription and Vietnam

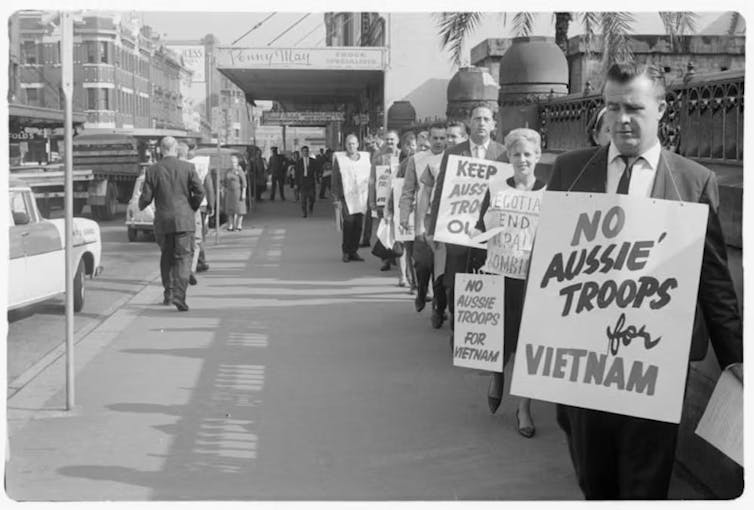

The next phase of veteran activism emerged in opposition to the Vietnam War. Australian forces deployed to Vietnam from 1962 to 1972, in an effort to contain the spread of communism. Although the war was widely supported in Australia, it also coincided with the expansion of National Service, conscripting 20-year-old men to support Australia’s Cold War commitments overseas.

Conscription ran counter to Australia’s historic pride in volunteerism in war, drawing opposition from some members of the veteran community.

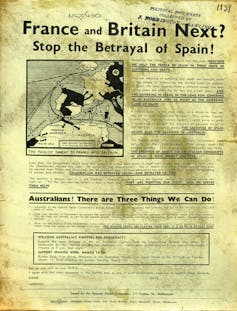

Martin Leslie Waddington, a second world war veteran, founded the Ex-Services Human Rights Association of Australia in 1966. The organisation harnessed the emerging rhetoric of human rights to position itself as advocating for “individual liberties [that] are being eroded around the world”, found historian Jon Piccini. Within a year, the association grew to over 500 members.

Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales and Courtesy SEARCH Foundation, CC BY

Like Throssell and others before them, Waddington and his organisation mobilised their privileged position as veterans in Australian society. They wore service ribbons, medals and badges to protests, recognising their war service lent respectability and authority to what were still largely fringe anti-war views. Members explained their military experiences led them “to affirm that war is a crime against humanity”.

Waddington was expelled from the RSL for his views. This led to the resignation of hundreds of members. Resigning veterans condemned the “hardening, intolerant attitude” that manifested in “hatred and fear of anybody or anything that is regarded as a threat to their carefully built up notions”.

Once again, the RSL tamped down the political diversity among veterans in Australia. The association’s activism was minimised by the Australian media, Piccini found. Historians agree the Australian media was broadly supportive of the war – and critical of the anti-war movement. “Cameramen seemed to avoid photographing our group”, the association’s newsletter reported. The news “may not want our ex-service background being noticed by the public”.

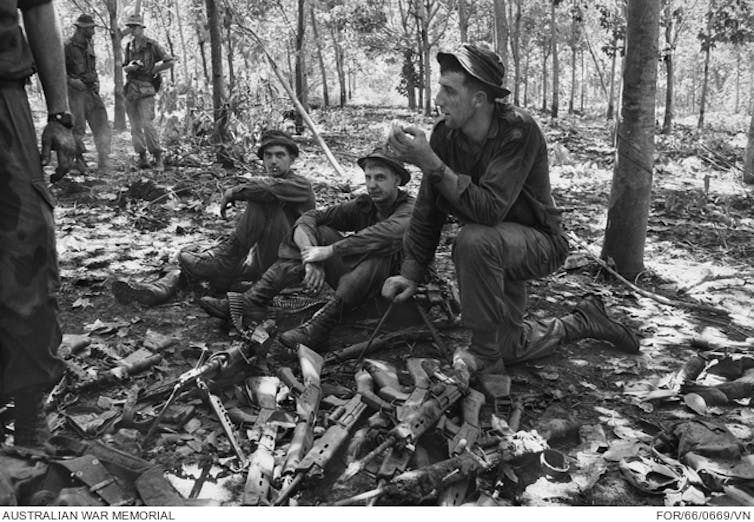

Yet some Australian forces in Vietnam were themselves turning against the war. From 2015 to 2017, I interviewed dozens of Vietnam veterans across Australia. A small handful of them became anti-war as a result of their service.

Rob de Kok, a conscript from country Victoria, told me he supported the war when he was called up:

All that shit, the Cold War business, meant that I actually went in willingly.

But his mind changed quickly:

either the first time you’re shot at, or the first time somebody you know actually gets hit […] you don’t have to stay long in a war before you actually think, “this is just ridiculous. This shouldn’t be happening.

Another soldier I spoke to, Gerry Binder, had come to Australia fleeing the Soviet occupation of Romania. He was a ”full tilt anti-communist” when he joined up in 1967. Binder supported the war, but once actually in Vietnam, he found himself “starting to question the wisdom of waging wars”. He’d “seen stuff over there that I wasn’t happy with”.

He remembered one particular incident where his unit discovered a pit and a rifle in the home of two elderly Vietnamese, and decided they were Viet Cong.

“We took them away as prisoners. Then the tank blew their shack to shithouse. Just destroyed it, just disappeared in a shower of sparks and flame,” he told me. “And I was not happy with that. I thought, these people are just harmless peasants.”

He said if he was in that area, “with bombs and bloody soldiers everywhere”, he’d dig a pit to hide in too – and find a rifle to defend himself. “That doesn’t mean they’re bloody Viet Cong or enemy or any of that sort of shit. It just means they’re terrified people living in a war zone.”

Yet even those Vietnam veterans who had come to oppose the war did not feel comfortable speaking out publicly in Australia. “From the moment I came back, I did my best to dissociate myself from everything,” de Kok explained. “I didn’t want to be a Vietnam vet, I didn’t want anybody to know about it.”

Terry Burstall, a veteran of the battle of Long Tan, reflected in his memoir that it was hard for soldiers to speak out against the war, because it would upset those who had lost their loved ones.

‘When you lose a son or husband in a war, there has to be at least a Cause – he died for his country, or defending our freedom, or something. In Vietnam none of these rationales could be used.

Australian War Memorial

This quiet opposition to the Vietnam War among the ranks was more widespread than is often acknowledged. It came up repeatedly in my interviews with Vietnam veterans who were otherwise conservative. “I did not agree with being there for sure,” one veteran told me. “I don’t think I was unique.”

Many felt the war in Vietnam was a case of fighting “other people’s wars”, an “insurance policy” for the US alliance. “Most people now see the folly of our involvement in the Vietnam War,” one veteran reflected. “I think most people now see it as having been a political war.” Some even indicated their experiences had led them to anti-war views.

One told me serving in Vietnam “greatly” changed his views:

To this day, I still think we should be bringing all our troops home from around the world.

However, most of the Vietnam veterans I spoke to shied away from the “anti-war” label. “That’s a big word,” said one, “it has a lot of meanings to it.”

Demonisation of the anti-war movement

This veteran alluded to the idea the anti-war movement was hostile, even abusive, to returning soldiers during the Vietnam War. But there is simply no historical evidence for this: not in footage of protests, nor in the extensive newspaper coverage of anti-war protests, nor in soldiers’ accounts during the war or immediately afterward.

Historians in both the US and Australia have researched this “memory myth” for decades. A memory myth is a false but widely held idea about the past, usually drawn from popular culture and frequently repeated in the media.

This myth emerged from the US Nixon administration’s attempt to discredit the anti-war movement, to undermine how many returning soldiers were joining the anti-war movement. This hostility towards returning soldiers became a recurrent trope in Vietnam War films in the late 1970s and early 1980s, including the first Rambo film, First Blood (1982).

After these films came out, the myth of anti-war abuse began to manifest in veterans’ memories in the 1980s. This fed into a surge of commemoration around the Vietnam War and fuelled the emerging Anzac Revival.

This myth has dominated the Australian memory of our role in Vietnam. It has shaped the way politicians, the Australian media and the Australian public talk about current and future wars. Negative perceptions of the anti-Vietnam War movement have been deployed time and again, to diminish the anti-war views expressed by soldiers and veterans.

Opposition to recent wars

In 1990 to 1991, Australia participated in the US-led Gulf War, in response to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait.

In 1991, seaman Terry Jones went “absent without leave” as the HMAS Adelaide was preparing to depart Perth for the Gulf. “I am not a coward and I would be prepared to fight for my country, but I am taking a political stand because this is not our war,” he declared.

He was scolded by the media for his protest. A Canberra Times editorial argued public support for Jones meant demonising other service personnel as “uninformed and lack[ing] in intelligence”. It would likely “make the sailors feel as unwelcome as the Vietnam veterans felt on their return to Australia”.

These same claims were repeated again a decade later when, in 2003, Australia joined the US-led Coalition of the Willing to invade Iraq. A significant minority of Australians protested the war was illegal, based on the lack of UN support and flawed intelligence about Iraq’s Weapons of Mass destruction capability.

Two veterans of the first Gulf War, Magnus Mansie and Brett Jones, returned their medals in protest of Australia’s participation in this war. They were barely discussed in Australian reportage of the enormous anti-war March 2003 protests. One article that did cover their protest was framed by a headline that implicitly undermined it: “Support the troops, PM tells protesters”.

In each of these cases, the protesting veterans were explicit that their opposition to war was about protecting Australian interests and values. Mansie, for instance, argued the Iraq War would “incite terrorism” and endanger Australians, something security experts agree was a lasting consequence of the War on Terror.

He also argued involvement in an illegal war was not in “the fighting spirit of our nation and its defence force personnel”. Like those volunteers on the International Brigades in the 1930s, Mansie invoked the Anzac legend to support his position, framing Australian warfare as defending fairness and righteous causes.

Yet when left-wing veterans have attempted to harness Australian military mythology to express their views, they have been undermined by the very organisations that claim to speak for them.

In 2005, Australian veterans of the second world war and INTERFET mission in Timor joined forces to protest Australia’s underhanded tactics in negotiating maritime boundaries with Timor.

The Timor Sea Justice Campaign put out an advert on Anzac Day, 2005, with second world war veterans reminding the public of “the Australian notion of a fair go”. The ad was pulled over criticisms from the RSL that it was “offensive” to “use the Anzac spirit as the basis for criticising the Government”.

Why is Australia hostile to anti-war veterans?

Why has Australia been so hostile toward soldiers and veterans who draw on their service to challenge war? The role of war history in Australian identity has played a part.

Historian Peter Stanley argues “Australia as a nation has been notably bellicose”, to the point “even the idea of ‘peace’ has not been a major part of its history”. Australian norms of masculinity, drawn from the image of the larrikin digger, emphasise stoicism and an easygoing nature. These traits do not sit comfortably with anti-war complaint.

Those who have spoken out against war have been accused of being weak and cowardly: Jones was branded a “whinger” by his commander for opposing the Gulf War. He was accused of leaving his mates “in the lurch”.

Another factor is the lack of representation. The Australian War Memorial, Australia’s primary body for recognising and remembering military service, has been reluctant to acknowledge that war has turned many soldiers against it.

In 1987, Thomson pitched a manuscript to the Australian War Memorial for publication based on his oral histories with radical diggers who joined the labour movement, but was rejected on the grounds their stories were unrepresentative of the first world war experience.

Around the same time, a handful of Vietnam veterans began producing anti-war art, including a travelling exhibition of veteran art that aimed to address the “lack of exposure of the problems resulting in and from” war. These veteran-artists continued to work and exhibit together for decades. But as a 2009 review found, the Australian War Memorial “has so far shown limited interest in subversive or ‘outsider’ art by veterans”.

The treatment of Anzac Day as a “sacred” day for veterans has also stymied protest and dissent. Gerry Binder, who created his blog Australian Veterans for Peace in reaction to the War on Terror, explained he avoids protesting on Anzac Day “because of the sensitivity regarding other veterans”.

This aversion to protesting on Anzac Day, when their views would get the most attention, is reinforced by the Australian media. After repeated Anzac Day controversies, the media seem to be reluctant to publicise anti-war veteran statements on Anzac Day.

In 2018, US marine and Australian Army veteran Chip Henriss was interviewed by an SBS journalist for Anzac Day. He condemned the tendency to “celebrate the fact that we went to war”. His interview was conducted in English, but for some reason, was only broadcast on SBS Mandarin.

Efforts by veterans to challenge Australia’s martial mentality have been stymied, too, by the institutions that seek to protect the Anzac legend from criticism. In addition to the longstanding conservatism of the RSL, splinter organisations, such as the Vietnam Veterans Association of Australia, challenged existing authorities on issues such as compensation – but remained “rousingly conservative when it comes to the big questions about the war”.

Veteran organisations are reluctant to support left-wing initiatives. The Australian War Powers Reform campaign seeks to ensure the decision to send service personnel to war should be made by parliament and supported by the public.

It included a “Veterans’ Appeal” to muster support from Australian Defence Force personnel to add weight to their campaign. Yet the campaign organisers – several veterans among them – told me “there seemed to be resistance from some [veterans’] orgs that we approached to them helping circulate information about the appeal”.

No space for dissenting veterans

There is no cultural space for dissenting veterans in Australia. They tend not to join veterans’ associations, or participate in local veteran community events.

Some of the veterans I spoke to initially participated in Anzac Day marches, but stopped attending after recognising how the day itself was exploited by conservative forces. “I don’t really want to be part of this,” realised one Vietnam veteran, “so I walked away from it.”

Veterans in the US have successfully situated their anti-war activism as a continuation of their service. But in Australia, it has been an ongoing struggle for veterans to find and support one another in protest.

Binder suggested the potential backlash deterred many veterans from speaking out:

when you’re talking to them privately, you might get a lot of anti-war sentiment being expressed, but publicly – they won’t go public.

This means other anti-war veterans are left with the impression they are alone in their opposition. “My only impression of veterans were people who were sort of loud and proud about their deeds,” explained de Kok. He believes there are many out there like him, who do not identify with the label of “veteran” at all.

The erasure of the political diversity of Australian veterans has ramifications for serving members today. The cloistered politics of the Australian Defence Force likely contribute to the massive problem with recruitment into the forces. The inhibition of political diversity among the ranks reflects what soldiers see in the broader veteran community. It limits much-needed cultural change among the forces.

In the 21st century, the Australian Defence Force has emphasised the importance of critical thinking among the ranks: as well as cultural competence, sensitivity and the ability to build trust with local populations. These skills are all necessary for missions that, in the words of Australian doctrine, seek to win the peace, as well as the war.

But scholars and journalists have recently revealed serving personnel have faced retribution and institutional abuse for questioning distorted intelligence or reporting allegations of war crimes up the chain of command.

The Australian Defence Force claims to value courage, which they define as “the strength of character to say and do the right thing, always, especially in the face of adversity”. But current and former personnel are not supported when they draw on their knowledge and experience to question existing agendas, strategies and missions.

Drawing on these critical voices of dissenting soldiers and veterans would be an asset to the Australian military. This would make it more representative of the views of all Australians – and improve its capability by listening to those who have experienced its mistakes.

![]()

This research was funded by the Centre for Contemporary Histories at Deakin University