Detta inlägg post publicerades ursprungligen på denna sida this site ;

Date:

Author: Rss error reading .

Original article: https://theconversation.com/art-deco-100-years-since-the-paris-exhibition-that-revolutionised-modern-design-255053

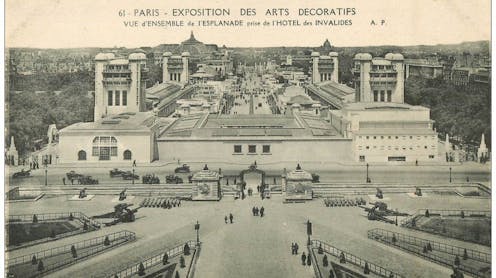

On 28 April 1925, the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts opened in Paris. It was a landmark event in the evolution of art, architecture and design, and aroused great interest both for the works on display and for their impact.

Wikimedia Commons

In interwar Spain, it was the most widely publicised event in architecture magazines, coinciding with a shift in the focus of these publications towards interior design and furniture.

The exhibition has been a source of interest and inspiration ever since the Second World War, and the abundance of published works on it is a testament to its continued significance. It marked a turning point in the aesthetic conception of the period, one that deliberately sought to distance itself from historicism and emphasise originality and novelty in both artistic and industrial creations.

The birth of “modern”

The Paris Exhibition’s lengthy gestation process generated great expectation. In 1911, René Guilleré, president of the Société des Artistes Décorateurs, proposed an international event that would reaffirm French supremacy in design, especially in the face of German competition.

Bibliotèque nationale de France

Approved in 1912, its celebration was originally slated for 1915. However, it was delayed by the First World War, and did not actually occur until 1925. Throughout this period, the exhibition was widely advertised in the press and specialist magazines, creating the opportunity to produce a new style.

The idea of innovation was reflected in the exhibition’s guidelines, which required works to be previously unpublished, and excluded any reproduction of historical styles. Its fourth article expressly stated that only works of “new inspiration and real originality” would be accepted, prohibiting copies and imitations from the past.

While it aimed to encourage a new aesthetic language in line with social and technological change, this guideline sparked debate over the interpretation of “modern”. The lack of clear criteria led to arbitrary decisions.

The exhibition therfore became a scene of tension between designers who embraced the radical avant-garde and those that, without renouncing modernity, maintained certain links with traditional styles.

Two visions of modernity

For more conservative architects and designers, the show represented the culmination of a style that had been in the making since the beginning of the 20th century.

Wikimedia Commons

It was instrumental in the international dissemination of the “1925 style” as it was then known. It was only in 1966, at the retrospective exhibition “Les Années 25”, held at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, that this style became known as Art Deco.

Most of the French and other European pavilions interpreted modernity as an expression of the style of the time, often fused with local elements. The Spanish pavilion was a prime example: designed by Pascual Bravo, it drew clear inspiration from the traditional styles of Andalusia.

Although the exhibition excluded historical styles, folk art – along with a range of other references such as exoticism, cubism, French neoclassicism and machinery – was incorporated into many projects. This demonstrated the diversity of approaches within Art Deco, where low-relief decoration and geometric motifs predominated.

Wikimedia Commons

However, the avant-gardists considered that the exhibition reinforced a decorative approach far removed from true modernity. The Belgian architect Auguste Perret, for instance, claimed that real art did not require decoration. For his part, Swiss architect Le Corbusier’s book L’Art décoratif d’aujourd’hui (The Decorative Art of Today), criticised the notion of a “modern decorative art”, and stated that true modernity should not include ornamentation – an idea that the Austrian Adolf Loos had already put forward years earlier.

Indeed, the Le Corbusier-designed L’Esprit Nouveau pavillion clashed with the exhibition’s predominant Art Deco style, as did Konstantin Melnikov’s Soviet pavilion and Aleksandr Rodchenko’s workers’ canteen. These works shocked the public and critics by presenting a radically different vision of modernity.

Wikimedia Commons

A 100-year legacy

One hundred years after its inauguration, the Paris Exhibition remains a milestone in the history of design. Its impact transcended the purely aesthetic, and it consolidated Art Deco as the one of the century’s great decorative styles. It also served as a stage for the emergence of the Modern movement, whose rationalist ideas would transform the design of the future.

Later examples of Deco’s influence included the Chrysler Building, the Empire State Building and chairs designed by Jacques Émile Ruhlmann, while Modern design gave us the clean lines of the Ville Savoye, the Bauhaus building in Dessau and furniture by Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret and Charlotte Perriand.

The coexistence of these two visions in the exhibition highlighted a key debate that still resonates today: the balance between tradition and innovation in design. Beyond its role in defining styles, the exhibition raised fundamental questions about the relationship between art and industry, the function of ornament, and the need to connect design with social demands. These tensions are still relevant today, where the challenges of combining creativity and industrial production persist.

The 1925 exhibition was therefore not only a showcase for the aesthetic change of its time, but a pivotal moment that continues to inspire contemporary design. Its legacy invites us to reflect on the nature of modernity, and how it evolves over time.

This article is part of the DISARQ project ’Aportaciones desde la arquitectura a la teoría, la pedagogía y la divulgación del diseño español (1925-1975)’ (’Architecture’s contributions to the theory, pedagogy and dissemination of Spanish design, 1925-1975’) (PID2023-153253NA-I00), financed by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 FEDER, EU.

María Villanueva Fernández y Héctor García-Diego Villarías are the project’s lead researchers.

Héctor García-Diego Villarías receives public funding for the DISARQ research project, which were obtained through a competitive open call.