Date:

Author: Stephanie Brodie, Research Scientist in Marine Ecology, CSIRO

Original article: https://theconversation.com/good-news-beach-lovers-our-research-found-39-less-plastic-waste-around-australian-coastal-cities-than-a-decade-ago-253221

Picture this: you’re lounging on a beautiful beach, soaking up the sun and listening to the soothing sound of the waves. You run your hands through the warm sand, only to find a cigarette butt. Gross, right?

This disturbing scene is typical of coastal pollution in Australia. But fortunately our new research shows the problem is getting better, not worse. Over the past ten years, the amount of waste across Australian coastal cities has reduced by almost 40%. We’re also finding more places with no rubbish at all.

We surveyed for debris in and around six Australian urban areas between 2022 and 2024. Then we compared our results to previous surveys carried out a decade ago. We found less coastal pollution overall and reset a new baseline for further research.

Our study shows efforts to clean up Australia’s beaches have been working. These policies, practices and outreach campaigns have reduced the extent of pollution in coastal habitats near urban centres. But we can’t become complacent. There’s plenty of work still to be done.

TJ Lawson

What we did

In Australia, three-quarters of the rubbish on our coasts is plastic. Even cigarette butts are mainly made of plastic.

To tackle the pollution effectively, we need to understand where the waste is coming from and how it gets into the environment.

Research has shown much of the coastal debris comes from local inland areas. Poor waste management practices can result in debris eventually making its way through rivers to the coast and out to sea.

We focused on urban areas because high population density and industrial activity contributes to waste in the environment. We examined six areas across Australia:

- Perth in Western Australia

- Port Augusta in South Australia

- Hobart in Tasmania

- Newcastle in New South Wales

- Sunshine Coast in Queensland

- Alice Springs in the Northern Territory.

These places represent a starting point for the national baseline. At each location we studied sites on the coast, along rivers and inland, within a 100 kilometre radius.

We inspected strips of land 2m wide. This involved two trained scientists standing in an upright position looking downward, slowly walking along a line surveying for debris items. Together they captured information about every piece of debris they came across, including the type of material and what it was originally used for (where possible).

What we found

On average, we found 0.15 items of debris per square metre of land surveyed. That’s roughly one piece of rubbish every five steps.

Plastic was the most common type of waste. But in many cases it was unclear what the item was originally used for. For example, fragments of hard plastic of unknown origin were found in a quarter of all surveyed areas.

Polystyrene fragments were the most common item overall (24% of all debris fragments). Other frequently encountered items included food wrappers or labels, cigarette butts, and hard plastic bottle caps or lids.

We found more waste near farms, industry and disadvantaged areas.

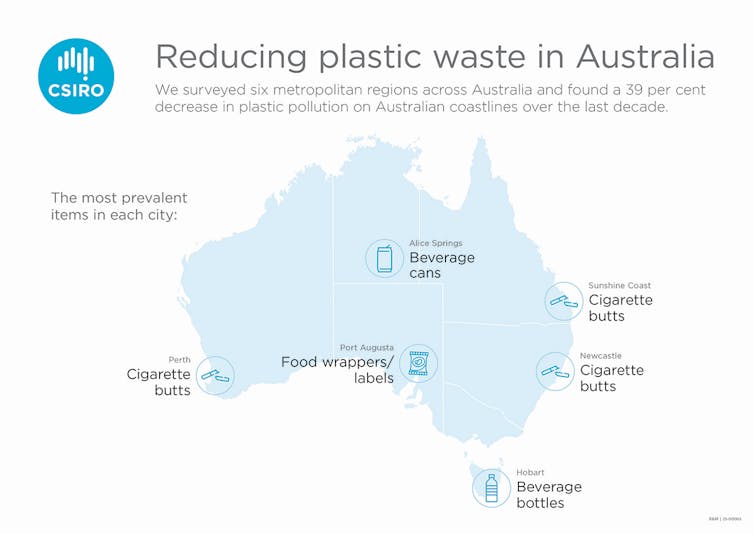

The types of waste varied among cities. For example, cigarette butts were the most prevalent items in Newcastle, Perth and the Sunshine Coast. But food wrappers and beverage cans were more prevalent in Port Augusta and Alice Springs, respectively.

Hobart had the highest occurrence of beverage bottles and bottle fragments.

CSIRO

Targeting problem items

Identifying the different types of litter in the environment can help policymakers and waste managers target specific items and improve waste recovery.

Research has shown container deposit legislation, which enables people to take eligible beverage containers to a collection point for a refund, has reduced the number of beverage containers in the coastal environment by 40%. Hobart did not have a container deposit scheme in place at the time of our survey.

Plastic bag bans can reduce bag litter. Now polystyrene food service items are becoming increasingly targeted by policymakers.

Caroline Bray

Making progress

When we compared our results to the previous survey from 2011-14 we found a 39% decrease in coastal debris. We also found 16% more areas where no debris was present.

Our results support previous research that found an ongoing trend towards less waste on Australian beaches.

We think our research demonstrates the effectiveness of improved waste management policies, campaigns such as the “Five R’s – Refuse, Reduce, Reuse, Repurpose, then Recycle” – as well as clean-up efforts.

It’s likely that increased awareness is making a big dent in the problem. But reducing the production of plastic, and invoking changes further up the supply chain, would likely further help reduce mismanaged waste in the environment.

Implications for the future

Measuring and monitoring litter can inform policymaking and waste management. Our research serves as a benchmark for evaluating and informing future efforts to reduce plastic waste.

We are heartened by the findings. But continued effort is needed from people across government, industry and Australian communities. Everyone needs to address how we produce, use and dispose of plastic for a cleaner and healthier planet.

Qamar Schuyler

![]()

As part of her role at CSIRO, Stephanie Brodie receives funding the federal Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, and the Australian Fisheries Management Authority.

Britta Denise Hardesty received funding for this work from the Department of Climate Change, Energy, Environment and Water. Shell Australia previously provided funding for this research via Earthwatch Australia for surveys and citizen science projects carried out between 2011 and 2014.