Date:

Author: Zhengyao Lu, Researcher in Physical Geography, Lund University

Original article: https://theconversation.com/consecutive-el-ninos-are-happening-more-often-and-the-result-is-more-devastating-new-research-251504

El Niño, a climate troublemaker, has long been one of the largest drivers of variability in the global climate. Every few years, the tropical eastern Pacific Ocean seesaws between warm (El Niño) and cold (La Niña) phases. This reshuffles rainfall patterns, unleashing floods, droughts and storms thousands of miles from the Pacific origin.

The 1997-98 and 2015-16 El Niño events, for instance, brought catastrophic flooding to the eastern Pacific while plunging Africa, Australia and southeast Asia into severe droughts.

These disruptions don’t just alter weather, but devastate crops, collapse fisheries, bleach coral reefs, fuel wildfires, and threaten human health. The 1997-98 El Niño alone caused an estimated US$5.7 trillion (£4.4 trillion) in global income losses.

Now, something more alarming is unfolding: both El Niño and La Niña are lingering longer than ever before, which is amplifying their destructive potential.

Traditionally, El Niño events lasted about a year, alternating with La Niña in an irregular cycle every two to seven years.

And normally when an El Niño or La Niña event ends, the disturbance to global weather patterns gradually subsides. But when these anomalies persist or re-emerge, the damage compounds and complicates recovery efforts. For instance, a single-year El Niño-driven drought can challenge agricultural systems, but consecutive years of drought could overwhelm them.

In recent decades, these climate patterns have been persisting longer and recurring more often. A striking example is the 2020-2023 La Niña, a rare “triple-dip” event that lasted for three years. Rather than returning to neutral conditions, these anomalies are prolonging devastation and making recovery increasingly difficult.

In a recent study, my colleagues and I revealed that multi-year Enso (El Niño-southern oscillation, or both warm El Niño and cold La Niña) events have been steadily increasing over the past 7,000 years, and are now more frequent than ever. This is due to a fundamental shift in Earth’s climate system.

Clear proof of this shift comes from ancient corals in the central Pacific. These fossilised time capsules preserve a climate record stretching back thousands of years. By analysing oxygen isotopes in their skeletons, scientists can reconstruct past ocean temperatures and Enso activity.

What we’ve found is remarkable: in the early Holocene (7,000 years ago), single-year Enso events were the norm. But over time, multi-year events have become five times more common.

To confirm this, we turned to sophisticated computer simulations that replicate Earth’s climate system. The latest advancements in these global climate models allow us to simulate Enso dynamics stretching back hundreds of millions of years, across vastly different climate conditions and continental arrangements.

In our study, we used a group of models contributed by international research teams to track Enso evolution over millennia, incorporating factors such as ocean circulation, atmospheric conditions, vegetation changes and solar radiation. The results align with coral records: Enso events have grown more prolonged over time.

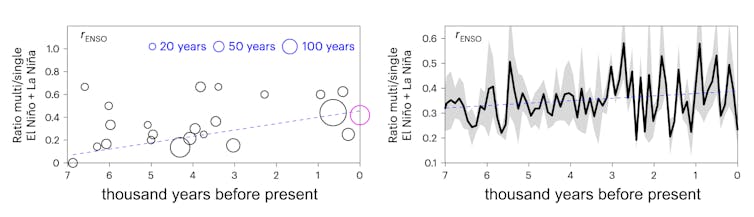

Look at the graphs below. On the left are black circles which represent fossilised coral slice records (bigger circles contain data for longer periods). The increasing trend (blue dashed line) shows the ratio of multi-year Enso events to single-year events increasing over the past 7,000 years (a ratio of 0.5 means one multi-year Enso event for every two single-year events). On the right, climate model simulations also show this ratio increasing.

Lu et al. (2025)/Nature

The role of Earth’s orbit and humans

This trend of Enso events lasting longer started gradually in the Holocene and is linked to changes in the Pacific Ocean’s thermocline, which is the boundary between warm surface waters and cooler deep waters. Over millennia, the tropical Pacific’s thermocline has become shallower and more stratified, enabling more efficient interaction between the atmosphere and ocean that allow El Niño and La Niña events to persist for longer.

The primary driver of this stratification has been the slow change in Earth’s orbit, which alters the distribution of solar energy our planet receives. These orbital variations have subtly influenced upper ocean temperatures in the tropical Pacific, nudging Enso towards longer phases. This slow process has unfolded naturally, but now there’s a new and powerful force accelerating it: human-driven climate change.

Greenhouse gas emissions, predominantly from burning fossil fuels, are turbocharging this trend. The extra heat trapped in the atmosphere and ocean is making conditions even more favourable for persistent Enso events, and possibly more intense. What was once a slow, natural evolution is now accelerating at an alarming rate. Unlike past climate shifts, this one is happening in our lifetimes, with consequences we can already see.

The implications are staggering. If Enso events keep lasting longer, we can expect more frequent and prolonged droughts, heatwaves, wildfires, floods and back-to-back intense hurricane seasons driven by multi-year Enso. Agriculture, fisheries, water supplies and disaster response systems will face increasing strain. Coastal cities, already struggling with rising seas, could face even more destructive storm surges fuelled by extended El Niño conditions.

This is less a scientific puzzle than a growing crisis. While we can’t change Earth’s orbit, we can cut carbon emissions, strengthen climate resilience efforts and prepare for more persistent extreme weather. The science is clear: El Niño and La Niña are sticking around longer, and their consequences will be felt across the globe. The time to act is now, before the next multi-year Enso shockwave hits.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 40,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

![]()

Zhengyao Lu receives funding from the Swedish Research Council, FORMAS and the Crafoord Foundation.