Date:

Author: Michael Newton, Lecturer, Centre for the Arts in Society, Leiden University

Original article: https://theconversation.com/shakespeares-cymbeline-explores-how-to-live-through-the-end-of-the-world-249190

Written in 1611, Shakespeare’s Cymbeline is a raw mess – full of feeling and as messy as life. The 18th-century man of letters, Samuel Johnson decried the play as a work of “unresisting imbecility”, a hotch-potch of incongruities.

It’s true that it’s hard to even know what kind of play Cymbeline is. The First Folio, the first collected edition of Shakespeare’s plays, presents it as the last of his tragedies. But it’s also, all at once, a history play, a pastoral, a fairytale, a pantomime and a tragicomedy.

Set in ancient Britain at the time of the birth of Christ, Cymbeline stitches together three plots. In one, Posthumus (the banished husband of Innogen, King Cymbeline’s daughter) accepts a wager with Iachimo that the sleazy Italian will not be able to seduce his wife. In the second, after 20 years, King Cymbeline’s abducted sons (and Innogen’s brothers) are restored to him. And in the third, refusing to pay tribute to the emperor, tiny Britain picks a fight with the majesty of imperial Rome.

What makes Cymbeline such a potent play for our own age of anxiety is how Shakespeare weaves a tale about the collapse of everything known, as connections dissolve, and lays out how we may discover ourselves anew in the radically altered world.

This article is part of Rethinking the Classics. The stories in this series offer insightful new ways to think about and interpret classic books and artworks. This is the canon – with a twist.

Written late in his career, in Cymbeline, Shakespeare rips up all the ways he’s been doing things and suddenly starts afresh. Here, some few years before his retirement, he foregoes the complex psychology of his great tragedies and opts for archetypes of fairytale and romance.

But in striking out for this new artistic territory, he also turns to himself as his own best source. Like an ageing rock band contracted for one last farewell tour, in Cymbeline, Shakespeare’s back playing the hits.

Like King Lear, Cymbeline is set in ancient Britain. Sneering Iachimo is Iago’s ghost and Posthumus, a dollar-store Othello.

Innogen is Shakespeare’s last cross-dressing heroine, passing as a boy, a faded echo of witty Rosalind of As You Like It and sad Viola of Twelfth Night. There’s fun in Rosalind and Viola’s changed identities, but Innogen puts on boy’s clothes to escape. Her father condemns her as disobedient for marrying Posthumus, and instead pushes her towards her step-brother, the fatuous bully Cloten.

Innogen’s time as a boy is joyless, as she learns that her beloved Posthumus wants her killed. She’s a new person now, not Innogen, but “Fidele”. Unmoored, adrift, she unwittingly finds her brothers, falls ill and mistakenly consumes a drug that puts her into a sleep so deep she appears to be dead.

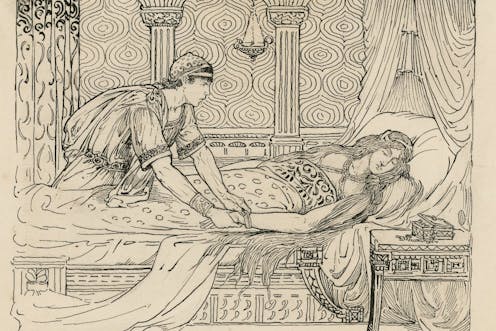

She wakes from this seeming death beside a headless body that she takes to be her murdered husband, but is in fact the villainous Cloten. Desperate with grief, she touches the flowers that have been strewn on the corpse, and smears herself with his blood.

It’s as stark a scene as Shakespeare ever wrote in its unstable unity of tender beauty and suffering. Innogen sighs: “These flowers are like the pleasures of the world, This bloody man, the care on’t,” and in that conjunction sums up the extremities of life and of this play. When a Roman soldier finds her, she tells him: “I am nothing; or if not, Nothing to be were better.”

Dying to live

Politically, too, things are disintegrating. The play multiplies broken bonds, unpaid debts and contracts denied – including both the marriage contract, and the debt of tribute owed to Rome by Britain.

Following Innogen’s passage through suffering and figurative death, Posthumus undergoes the same process. He has already earned his name by outliving his parents.

Reduced, like Innogen, to all but nothing, believed to be dead, but actually in prison, Posthumus receives a vision of his dead family and of forgiving Jove, the divine father of the Roman Gods. Love and social unity have died, but in this mystical scene, the possibility returns of renewal.

Both Innogen and Posthumus must “die” to live. Off stage, in distant Bethlehem, a nativity takes place that signals the death of the old Rome – but also the regeneration of all things. And so the story commits itself to the reconciliation achieved in wonder.

This is a play where the word “miracle” becomes a verb, just as Innogen and Posthumus, and old, foolish King Cymbeline himself come to understand how even the most distressed life may open to bliss. “The gods do mean to strike me to death with mortal joy,” declares an amazed Cymbeline, as the play offers us a vision of that astonishing unity of suffering and redemption.

We may doubt that such wonder could exist for us today. But Shakespeare’s full look at the worst enables us too to imagine the sense of hopeful possibility found in his brilliant conclusion. It is a wonderful play.

Beyond the canon

As part of the Rethinking the Classics series, we’re asking our experts to recommend a book or artwork that tackles similar themes to the canonical work in question, but isn’t (yet) considered a classic itself. Here is Michael Newton’s suggestion:

There’s no other work of art so chaotic and so alive as Cymbeline. But H. F. M. Prescott’s The Man on a Donkey (1952) runs it close. I only discovered this novel a year ago, and I find it astonishing that so great a book could have remained hidden so long. Prescott follows Cymbeline in manifesting hope in a time of social collapse. It’s a novel of Henry VIII and the Reformation, centred on the “Pilgrimage of Grace”, when loyal Catholics rebelled against the dissolution of the church.

I read it while recovering from surgery, and it was just as well. If I had read it while at work I would have had to steal time off constantly to return to it. There are few novels so deep, so compelling, so beautiful. Like Cymbeline, it breaks all the rules of how to make a work of art, and caught up in its story you find out how little those rules matter when face to face with the complexity of the world and the depth of human beings.

![]()

Michael Newton does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.