Date:

Author: Frédéric Fréry, Professeur de stratégie, CentraleSupélec, ESCP Business School

Original article: https://theconversation.com/from-ibm-to-openai-50-years-of-winning-and-failed-strategies-at-microsoft-253576

Microsoft celebrates its 50th anniversary. This article was written using Microsoft Word on a computer running Microsoft Windows. It is likely to be published on platforms hosted by Microsoft Azure, including LinkedIn, a Microsoft subsidiary with over one billion users. In 2024, the company generated a net profit of $88 billion from sales worth $245 billion. Its stock market value is close to $3,000 billion, making it the world’s second-most valuable company behind Apple and almost on a par with NVidia. Cumulative profits since 2002 are approaching $640 billion.

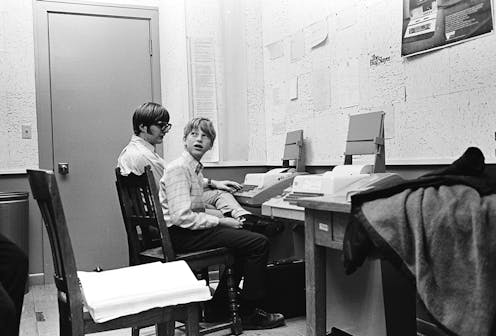

And yet, 50 years ago, Microsoft was just a tiny computer company founded in Albuquerque, New Mexico by two former Harvard students, Bill Gates and Paul Allen, aged 19 and 22. The twists and turns that enabled it to become one of the most powerful companies in the world are manifold, and can be divided into four distinct eras.

First era: Bill Gates rides on IBM’s shoulders

At the end of the 1970s, IBM was the computer industry’s undisputed leader. It soon realized that microcomputers developed by young Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, such as the Apple II, would eventually eclipse IBM’s mainframes, and so the IBM PC project was launched. However, it soon became clear that the company’s hefty internal processes would prevent it from delivering a microcomputer on schedule. It was therefore decided that various components of the machine could be outsourced using external suppliers.

A weekly e-mail in English featuring expertise from scholars and researchers. It provides an introduction to the diversity of research coming out of the continent and considers some of the key issues facing European countries. Get the newsletter!

Several specialized companies were approached to provide the operating system. They all refused, seeing IBM as the enemy to be destroyed, a symbol of centralized, bureaucratic computing. Mary Maxwell Gates, who sat on the board of an NGO next to the IBM chairman, suggested the name of her son William, nicknamed Bill, who had just founded Microsoft, and the first contact was established in 1980.

The problem was that Microsoft was focused on a programming language called BASIC and certainly not specialized in operating systems. Not that this was ever going to be a problem for Bill Gates, who, with considerable nerve, agreed to sign a deal with IBM to deliver an operating system he didn’t have. Gates then purchased the QDOS system from Seattle Computer Products, from which he developed MS-DOS (where MS stands for Microsoft).

Gates, whose father was a founding partner of a major Seattle law firm, then made his next move. He offered IBM a non-exclusive contract for the use of MS-DOS, which gave him the right to sell it to other computer companies. IBM, which was not used to subcontracting, was not suspicious enough: the contract brought fortunes to Microsoft and misery to IBM when Compaq, Olivetti and Hewlett-Packard rushed to develop IBM PC clones, giving birth to a whole new industry.

Success followed for Microsoft. It not only benefited from IBM’s serious image, which appealed to businesses, but also received royalties on every PC sold on the market. In 1986, the company was introduced on the stock market. Bill Gates, Paul Allen and two of their early employees became billionaires, while 12,000 additional Microsoft employees went on to become millionaires.

Second era: Windows, the golden goose (courtesy of Xerox)

In the mid-1980s, microcomputers were not very functional: their operating systems, including Microsoft’s MS-DOS, ran with forbidding command lines, like the infamous C:/. This all changed in 1984 with the Apple Macintosh, which was equipped with a graphic interface (icons, drop-down menus, fonts, a mouse, etc.). This revolutionary technology was developed in Xerox’s research laboratory, even though the photocopy giant failed to understand its potential. On the other hand, Steve Jobs, Apple’s CEO, was largely inspired by it: to ensure the success of the Macintosh computer, Jobs asked Microsoft to develop a customized version of its office suite, in particular its Excel spreadsheet. Microsoft embraced the graphic interface principle and launched Windows 1 in 1985, which was soon followed by the Office suite (Word, Excel and PowerPoint).

Over the following years, Windows was further improved, culminating in Windows 95, launched in 1995, with an advertising campaign costing over $200 million, for which Bill Gates bought the rights of The Rolling Stones’ “Start Me Up”. At the time, Microsoft’s world market share in operating systems exceeded 70%. This has hardly changed since.

In 1997, Microsoft even went so far as to save Apple from bankruptcy by investing $150 million in its capital in the form of non-voting shares, which were sold back three years later. During one of his famous keynote speeches, Steve Jobs thanked Bill Gates by saying: “Bill, thank you. The world’s a better place.” This bailout also put an end to the lawsuit Apple had filed against Microsoft, accusing it of copying its graphic interface when designing the Windows operating system.

Third era: bureaucratization, internal conflicts and a failed diversification strategy

In the mid-1990s, computing underwent a new transformation with the explosion of the World Wide Web. Microsoft was a specialist in stand-alone PCs, with a business model based on selling boxed software, and it was ill-prepared for the new global networks. Its first response was to develop Internet Explorer, a browser developed from the takeover of the Mosaic browser designed by the Spyglass company, a bit like MS-DOS in its day. Internet Explorer was eventually integrated into Windows, prompting a lawsuit against Microsoft for abuse of its dominant position, which could have led to the company’s break-up. New competitors, such as Google with its Chrome browser, took advantage of these developments to attract users.

In 2000, Bill Gates handed over his position as Microsoft CEO to Steve Ballmer, one of his former Harvard classmates, whose aim was to turn the company into an electronics and services company. Over the next fifteen years, Ballmer embarked on a series of initiatives to diversify the company by including video games (Flight Simulator), CD encyclopedias (Encarta), hardware (mice, keyboards), MP3 players (Zune), online web hosting (Azure), game consoles (Xbox), phones (Windows Phone), tablets and computers (Surface).

While some of these products were successful (notably Azure and Xbox), others were bitter failures. Encarta was quickly swamped by Wikipedia and Zune was no match for Apple’s iPod. Windows Phone remains one of the greatest strategic blunders in the company’s history. In order to secure the company’s success in mobile telephony and compete with the iPhone, Microsoft bought the cell phone division of Finland’s Nokia for $5.4 billion in September 2013. The resulting integration was a disaster: Steve Ballmer wanted Microsoft’s phones to use a version of Windows 10, making them slow and impractical. Less than two years later, Microsoft put an end to its mobile phone operations, with losses amounting to $7.6 billion. Nokia was sold for just $350 million.

One of the outcomes of Microsoft’s multiple business initiatives has been an explosion in the number of its employees, from 61,000 in 2005 to 228,000 in 2024. Numerous internal disputes broke out between different business units, which sometimes refused to work together.

These turf wars, coupled with pervasive bureaucratization and effortless profitability (for each Windows installation, PC manufacturers pay around $50, while the marginal cost of the license is virtually zero), have hindered Microsoft’s capacity for innovation. Its software, including Internet Explorer 6 and Windows Vista, was soon mocked by users for its imperfections, which were continually plugged by frequent updates. As some people noted, Windows is equipped with a “safe” mode, suggesting that its normal mode is “failure”.

Fourth era: is Microsoft the new cool (thanks to the Cloud and OpenAI)?

In 2014, Satya Nadella replaced Steve Ballmer as head of Microsoft. Coming from the online services division, Nadella’s objective was to redirect Microsoft’s strategy online, notably by developing the Azure online web hosting business. In 2024, Azure became the world’s second-largest cloud service behind Amazon Web Services, and more than 56% of Microsoft’s turnover came from its online services. Nadella changed the company’s business model: software is no longer sold but available on a subscription basis, in the shape of products such as Office 365 and Xbox Live.

Along the way, Microsoft acquired the online game Minecraft, followed by the professional social network LinkedIn, in 2016, for $26.2 billion (its largest acquisition to date), and the online development platform GitHub in 2018 for $7.5 billion.

Between 2023 and 2025, Microsoft invested more than $14 billion in OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, giving it a particularly enviable position in the artificial intelligence revolution. ChatGPT’s models also contribute to Microsoft’s in-house AI, Copilot.

Over the past 50 years, thanks to a series of bold moves, timely acquisitions and failed strategies to diversify, Microsoft has evolved significantly in its scope, competitive advantage and business model. Once stifled by opulence and internal conflicts, the company seems to have become attractive again, most notably to young graduates. Who can predict whether Microsoft will still exist in 50 years? Bill Gates himself says the opposite, but he may be bluffing.

![]()

Frédéric Fréry ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d’une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n’a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.