Kakapåkaka kaka

En ny klassiker kan man kalla det. Jag tog två kakor och slog ihop till en. I botten är det mördeg och ovanpå en havrekaka. Det blev en av mina favoritkakor. Lätta att göra är de också. Recept Ugnstemperatur 175 Läs mer…

Nyheter och länkar - en bra startsida helt enkelt |Oculus lyx vitae

En ny klassiker kan man kalla det. Jag tog två kakor och slog ihop till en. I botten är det mördeg och ovanpå en havrekaka. Det blev en av mina favoritkakor. Lätta att göra är de också. Recept Ugnstemperatur 175 Läs mer…

I live on the edge of Parramatta, Australia’s fastest-growing city, on the kind of old-fashioned suburban street that has 1950s fibros constructed in the post-war housing boom, double-storey brick homes with Greek columns that aspirational migrants built in the 1970s and half-crumbling, Federation-era mansions once occupied by people whose names still appear in history textbooks.

Parramatta’s population is predicted to almost double in the next 20 years. My street, like so many others, has recently been rezoned for high-density living. Many of these houses are being sold to developers.

It’s a local story but it’s also a national one: suburbs near our cities are disappearing everywhere along with the crucial histories of Australian life they represent.

Australia is still a suburban nation: 70% of us live in the suburbs and this figure is increasing with the rapid growth of “McMansion” areas in the far outskirts of our cities.

Suburbia looms large in our imagining of ourselves, so what happens when we lose those suburban streets whose houses are too young to be heritage-listed but still old enough to tell an important story of our social and economic history? As urban researcher Larry Bourne argued, we have yet to really write the history of suburban life because we haven’t paid enough attention to recording the private everyday experiences of people and their homes there.

So that’s what I’ve been doing for the past several months, walking the street with suburban photographer Garry Trinh and talking to my neighbours about their relationships with their homes before they are lost.

Read more:

Reimagining Parramatta: a place to discover Australia’s many stories

‘A different attitude to life’

A few houses down from me, Craig lives in a cottage that he believes “shows a different attitude towards life”. He spends his weekends restoring parts of his home.

It takes a lot of time to maintain. People took longer to do things. They had a different sense of time – they did things one time so they didn’t have to do it again.

Craig in front of his home.

Photo: Garry Trinh

Craig’s livingroom.

Photo: Garry Trinh

He enjoys the idea that living in a house like this “you grow old together”. He shows me the places where the tiles on the floor don’t fit perfectly. The “walls and roofs are never even”, but that’s part of the place’s charm – you can see where others have added a living room or tried to fix a leak.

These homes have layers of history that don’t exist anywhere else.

Craig in his backyard.

Photo: Garry Trinh

To Craig, these houses represent why other generations felt more of the kind of safety and security that allowed them to build a greater sense of community.

You used to buy one house and you never changed it, one car […] people stayed in the same place […] people feel so restless now because we are no longer safe. Everything changes. Our houses are rezoned. There’s no certainty.

Read more:

A city that forgets about human connections has lost its way

‘Edible things in people’s yards’

Jenny’s parents bought the largest block on the end of the street because the previous owners refused to sell to developers. She recently moved back home to care for her mother.

It’s a sprawling Federation-era home called “Coo-Wong” and it feels like big history must have happened there, despite its absence from any local history archives. There are clues, though, about the kind of people who might have lived here before: Chinese coins found on the property, a shed full of bric-a-brac.

Jenny and her mum on their porch.

Photo: Garry Trinh

Mostly, the whole family lives in the kitchen or the light-filled corner at the back of the house where Jenny’s mother grows flowers. Her father’s family lost everything during the Cultural Revolution and he moved here to find a better life. He’s in the building industry and their home is filled with the spare parts from other houses, doors, drawers and other supplies that might go into extending or renovating their home one day.

Jenny and her parents in the kitchen.

Photo: Garry Trinh

Jenny’s mum with her plants.

Photo: Garry Trinh

The Dish.

Photo: Garry Trinh

Jenny remembers when they moved into the neighbourhood there was an older generation of people who embraced them. There were fruit trees and “all of these edible things in people’s yards”. In their backyard, a giant satellite dish, which her parents bought to watch their shows from China, still looms big even if it isn’t needed anymore.

It’s these small details in Jenny’s home that tell the larger story of how various generations of migrants sewed themselves into the fabric of our suburbs.

New apartments and old houses.

Photo: Garry Trinh

Read more:

Chinese-Australians have a sense of dual ’belonging’: Lowy poll

Different versions of one house

George, his wife, Jennifer, and their two adult children live in the house George’s father built in 1973 when the street was filled with vacant blocks. His family was the first to move here from their village in Lebanon, so their house became a kind of community hub – there were always people there.

George’s family passed the plans he used to build the house onto other Lebanese families that moved in. It means there are slightly different versions of this house in many other places on the street.

George on his chair.

Photo: Garry Trinh

George and the family.

Photo: Garry Trinh

George’s dad and his uncles built many houses in this area together. Sometimes they didn’t quite get it right though: only one door in their house is hung straight – all the rest are hung backwards. The family has been trying to restore parts of the house for a long time, including the Art Deco railings and Victorian lights.

As an expert in post-war housing, Mirjana Lozanovska says this layering of architectural details found in these post-war suburban homes “expanded the image and aesthetic spectrum of what it is to be Australian”.

George and Jennifer in the livingroom.

Photo: Garry Trinh

The family and the skyline.

Photo: Garry Trinh

Read more:

City planners love infill development. So why are cities struggling with it, and how can they do better?

A long row of houses for sale

Carol lives in a long row of houses at the end of the street that are all for sale. She has, to put it lightly, a lot of stuff. Her odd collection of tents and furniture and well-loved succulents spill from her house to its immense lawns.

The quest for affordable housing has pushed Carol further and further west over time. When the landlord sells the house she’ll head further away, looking for some other suburban street where the houses are still intact and maybe there’ll still be lemon trees.

Carol’s house is for sale.

Photo: Garry Trinh

Carol in her yard.

Photo: Garry Trinh Läs mer…

Seventy thousand years ago, the sea level was much lower than today. Australia, along with New Guinea and Tasmania, formed a connected landmass known as Sahul. Around this time – approximately 65,000 years ago – the first humans arrived in Sahul, a place previously devoid of any hominin species.

Due to the patchy nature of the archaeological record, researchers still don’t have a full picture of the routes and speed of human migration across the region.

In research published in Nature Communications, our team has reconstructed the evolution of the landscape during this time. This allowed us to better understand the migration strategies of the first peoples in what is now Australia, along with the places they lived.

Read more:

Fifty years ago, at Lake Mungo, the true scale of Aboriginal Australians’ epic story was revealed

Walking over a changing landscape

When trying to understand the dispersion of first humans in Sahul, one overlooked aspect has been the impact of the changing landscape itself.

Our planet’s surface is constantly shifted by various physical, climatic and biological processes, changing on a grand scale over geological time – a process known as landscape evolution.

We used a landscape evolution model that details climatic evolution from 75,000 to 35,000 years ago.

The model allows for a more realistic description of the terrains and environments inhabited by the first hunter-gatherer communities as they traversed Sahul.

Read more:

Scientists just revealed the most detailed geological model of Earth’s past 100 million years

On top of the evolving landscape, we then ran thousands of simulations, each describing a possible migration route.

We considered two entry points into Sahul: a northern route through West Papua (entry time: 73,000 years) and a southern one from the Timor Sea shelf (entry time: ~75,000 years).

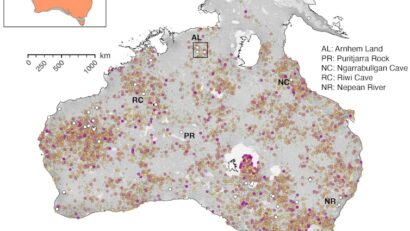

Results from our simulations predicted migration routes passing through 34 of the 40 archaeological sites older than 35,000 years (white circles are identified archaeological sites). Colours represent the number of moves between consecutive circles; the size of the circle is scaled based on the cumulative distance travelled by groups of hunter-gatherers.

Salles et al., Nature Communications (2024)

From these simulations, we calculated the speeds of migration based on available archaeological sites. Estimated speeds range between 0.36 and 1.15 kilometres per year. This is similar to previous estimates, suggesting people spread across the continent quite rapidly.

For both scenarios, our simulations also predicted a high likelihood of human occupation at many of the iconic Australian archaeological sites.

Probability of human presence across Sahul by 35,000 years ago, combining the northern and southern entry points. White circles indicate locations of archaeological sites. Grey lines overlaying the map show the dominant movement corridors interpreted as super-highways of human migration across Sahul before 50,000 years ago.

Salles et al., Nature Communications (2024)

Following rivers and coastlines

From the predicted migration routes, we produced a map of most likely visited regions, with probability of human presence as shown above.

We found that human settlers would have dispersed across the continental interior along rivers on both sides of Lake Carpentaria (the modern Gulf of Carpentaria). The first communities would have mainly been foraging along the way, following water streams. They also travelled along the receding coastlines as sea levels rose once more.

Based on our model, we didn’t identify well-defined migration routes. Instead, we saw a “radiating wave” of migrations.

However, our model did indicate a high likelihood of human presence near several already-proposed most likely pathways of Indigenous movement (called super-highways), including those to the east of Lake Carpentaria, along the southern corridors south of Lake Eyre, and traversing the Australian interior.

Read more:

We mapped the ’super-highways’ the First Australians used to cross the ancient land

We could predict archaeological sites

There’s one particularly interesting outcome from our map that shows the probability of human presence in Sahul. In a cost-effective way (without needing to travel across the entire continent), it could potentially pinpoint areas of archaeological significance.

Our approach can’t tell us how well a given location might be preserved for archaeological finds. However, our simulations do give an indication of how much specific sites may have eroded or received extra sediment.

We could use this to estimate if artefacts at a potential archaeological site have moved or been buried over time.

Our study is the first to show the impact of landscape changes on the initial migration on Sahul, providing a new perspective on its archaeology. If we used such an approach in other regions as well, we could improve our understanding of humanity’s extraordinary journey out of Africa. Läs mer…

The U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments on April 25, 2024, in a case that will change the course of American history. That case is Trump v. United States, in which the justices have been asked to decide whether and to what extent former President Donald Trump – or any president – can be criminally prosecuted for actions taken while in office.

The case specifically relates to special counsel Jack Smith’s charges that Trump attempted to subvert the 2020 presidential election. But the court’s decision will also apply to larger questions about the limits of presidential power and the role of the legal system in constraining executive actions.

Politics editor Naomi Schalit interviewed constitutional law scholar Claire Wofford, a political scientist at the College of Charleston, who said the implications of the case went beyond Trump’s case to “how future presidencies might operate.”

Justice Neil Gorsuch said, “We’re writing a rule for the ages.” The justices seemed very aware that the case in front of them was about former President Donald Trump, but it was about much more than that as well, wasn’t it?

I would absolutely agree with that. The justices raised a variety of concerns about the implications of deciding this case. Several of the justices, across the ideological spectrum, were very concerned about the practical implications of allowing a president to have immunity to some extent, or not allowing the president to have immunity.

Justice Samuel Alito seemed really concerned about the president being subject to political prosecution if he were not protected by immunity. Alito spoke of the president being in a “peculiarly precarious position.” Justice Brett Kavanaugh seemed to also be concerned with implications of a finding of no presidential immunity, raising the specter of what he called “cycles” of prosecutions.

On the flip side, several of the more liberal justices like Ketanji Brown Jackson and Elena Kagan raised the question of what would it mean if the president did have immunity – whether it would mean an unbounded executive. Jackson, in particular, talked about how we shouldn’t be concerned that the president would be chilled in his actions if he were potentially subject to prosecution.

“I think we would have a significant opposite problem if the president wasn’t chilled,” she said. She said a president could enter office “knowing that there would be no potential penalty for committing crimes.” She said, “I’m trying to understand what the disincentive is from turning the Oval Office into the seat of criminal activity in this country.”

Then-President Donald Trump speaks to supporters near the White House on Jan. 6, 2021.

Mandel Ngan/AFP via Getty Images

It seemed like everyone, from the attorneys for Trump and the Department of Justice to the justices themselves, wanted to find some middle ground where there was some, but not total, immunity for the president.

It didn’t seem to me that any of the justices want to conclude that the president is absolutely immune or that the president can always be criminally prosecuted. There’s going to be some gray area where some of what a president does can be subject to prosecution and some of what he does cannot. There was a lot of back and forth about what line would be drawn.

The justices want to be able to draw a distinction so that a president obviously can be held accountable under criminal law in certain extreme situations. But then some of what he does simply has to be considered part of his core executive function and within his discretion.

If they go that route, they will try to formulate a legal rule that draws the line between what kind of conduct is protected from prosecution and what kind of conduct is not protected. There were many options for that line that were put on the table during the argument. It doesn’t seem to me there was one clear position or another favored at the argument. But if the justices do try to formulate a rule, I would not expect a quick ruling.

Isn’t there another scenario, where they don’t get into a complex description of what’s on this side of the line and what’s on that side of the line?

Several of the justices pointed out that even if they decided some of Trump’s actions were official and therefore protected from immunity, the trial could still go forward on what both sides agree are his private actions. Jackson made a point at the end, asking the Justice Department’s attorney whether there are enough private actions taken by the president that the case could go to trial simply on those? The attorney said yes.

Anti-Trump protesters demonstrate outside the Supreme Court on April 25, 2024.

Mandel Ngan/AFP via Getty Images

Thinking about the role and power of the president, what’s the deeper meaning of today’s argument?

Today’s argument touches on the balance of power between Congress, the executive branch and the judiciary. Trump’s lawyer was arguing that the executive branch, for reasons of functionality, has to have some sphere in which it can operate alone and the judiciary has no ability to oversee what they do. The case also relates to broad questions about checks and balances and how the framers intended our government to function. In the background is the sweeping question about the rule of law, and whether or not certain individuals – including those who are charged with implementing that law and executing that law – are also subject to it.

George Washington was inaugurated as the nation’s first president on March 4, 1797. From then until now, the idea of a president violating criminal law has not been dealt with at the U.S. Supreme Court. What does that tell us?

It tells us one of two things. One, the system we have works. This is the argument that the Department of Justice was making, that the reason we haven’t been in the situation before is because we’ve never had a president like Donald Trump, either because Donald Trump is the type of character we’ve never had before or, alternatively, because presidents knew they would be subject to criminal prosecution and therefore were constrained in their behavior.

From the alternative side, of course, the argument is that we’ve never had this because nobody’s ever gone after a president with such political vehemence and nobody’s ever wanted to get rid of a president as badly as they want to get rid of President Trump. I think the obvious pushback would be that’s really not an accurate reading of American history. Plenty of presidents have been hated by their political opponents who tried to get rid of them one way or another.

We are at a crux in history, where the intersection between the executive and the judicial branches is being stress-tested like it never has before. And my hope is that the judiciary performs its job and the system remains intact.

I wish there were a different vehicle through which the court could resolve this question, and that it didn’t feel to so many people like the fate of our government, and the stability of our system, was on the line.

Is it?

It is if the court doesn’t do its job. If it does not make a clear, resounding statement that the president is not above the law, then I think we have a serious problem. Läs mer…

Note: The following article contains spoilers about the Netflix series “3 Body Problem.”

I first encountered the three-body problem 60 years ago, in a short story called “Placet is a Crazy Place” by American science fiction writer Frederic Brown.

In Brown’s story, Placet is a planet in a figure-of-eight orbit around two stars, one of which is composed of ordinary matter, the other of anti-matter. The closeness of the two stars cause time and space to become wonderfully distorted so that Placet can eclipse itself. But, intriguingly, the orbit is assumed to be stable and predictable.

Chinese science fiction writer Liu Cixin’s epic trilogy, Rememberance of Earth’s Past, returns to imagining what could happen when three celestial bodies are in orbit around each other. The first instalment, The Three-Body Problem, has been adapted into a series by Netflix.

The trailer for ‘3 Body Problem,’ Netflix’s adaptation of Liu Cixin’s novel.

The opening scenes of 3 Body Problem, set in Beijing in the early days of the Cultural Revolution, are particularly powerful. The characters in the series are flawed — the scientists are highly intelligent, but their ambitions, failings and fears are all too clear.

Random motion

The plot of 3 Body Problem involves an alien race, known as the Trisolarians, inhabiting a planet orbiting a nearby star system, known as Alpha Centauri. This consists of three stars that follow continuously changing orbits, causing the planet to go from bitter cold to searing heat in a matter of minutes.

The motion of the stars is unpredictable, so the Trisolarians cannot anticipate the arrival of the so-called chaotic eras that lead to the planet-wide destruction of their environment.

Intriguingly, Alpha Centauri actually is a triple-star system, consisting of two stars that orbit each other closely over a period of nearly 80 years, and a much more distant third star. This is very different from the system represented in 3 Body Problem.

So could we imagine a system where the stars are so close together in their orbits that their motion becomes random?

A three-body system made up of the stars Alpha Centauri A and Alpha Centauri B (shown here), plus the faint red dwarf Alpha Centauri C, also known as Proxima Centauri.

(ESA/NASA)

Possible orbits

The answer lies at the heart of theoretical physics. Isaac Newton famously solved the two-body problem for the Earth-moon system in the 1660s, so we can predict the moon’s orbit with extraordinary precision.

It is a little surprising that this works so well, because we are ignoring the sun which would turn it into a three-body problem. The trick to handling this (one of many) is that we can find a solution that works for the Earth-moon and then add in the effect of the sun, which turns out to be small.

We have learned a great deal since Newton. There is no general solution for the three-body problem: we cannot write down a formula for how three bodies will move in general. We have found a whole host of special cases; even the figure-of-eight orbit of the fictional Placet is possible.

Also, the James Webb telescope has been ingeniously placed to provide another solution for the three-body problem. It orbits around the sun, beyond the moon’s orbit of the Earth, so it can be shielded from radiation as much as possible.

It is complicated but straightforward for a computer to find solutions for the three-body problem. Cosmologists have been using computational analysis to construct increasingly complex models of how the universe evolved from an almost totally uniform beginning to its present stage. These models typically run with more than 10 billion bodies.

Chaotic systems

So why should we be interested in something as mundane as three bodies? Because if we have a system of three objects, all massive and fairly close, their motion is chaotic. This means that even though we can find out almost exactly what happens to them over a short period of time, it becomes unpredictable over a long time. But note that I have not told you what long and short means in this context.

In this animated rendering of the three-body problem, three bodies orbit each other in a random manner.

(Dnttllthmmnm/Wikimedia Commons), CC BY

We can get a feeling for this if we look at the weather, another chaotic system, and specifically hurricanes. We can accurately predict where a hurricane will make landfall 12 hours in advance — two days in advance we can make a rough prediction, but a week in advance is impossible.

As three bodies in orbit move, they dance across the sky in an extraordinarily complex fashion. We have no way of guessing where each of the bodies might be located in 1,000 years. They may not even be around: there are examples where one of the stars in a polyamorous threesome would be ejected totally, leaving behind a double-star system.

Read more:

Planet cannibalism is common, says cosmic ’twin study’

Unpredictable systems

In 3 Body Problem the challenge is that the orbits cause the climate to flip with essentially no warning. This is characteristic of a different kind of situation, a so-called stochastic problem.

A classic example is a drunk trying to navigate his way to the door, when every step is followed by another in a random direction. You cannot predict where the next step will take him, but you can say that he will eventually reach the door. It is a little bit scary that such systems are at the heart of our civilization, as demonstrated by the gyrations of the stock market. But stars — and the climate they produce — are not stochastic.

The fictional Alpha Centauri that the Trisolarians inhabit represents a chaotic system, predictable accurately in the short term but unpredictable over thousands of years. But it would be much simpler for them to predict it than to invade Earth. As with a lot of science fiction, enjoy it for the fiction and not the science. Läs mer…

As university campuses in both Canada and the United States are witness to ongoing student protests against the Israel-Hamas war amid campus challenges negotiating free expression and protection from harm, some academics are expressing concern about an Ontario government bill the government says aims to ensure safety and support for post-secondary students.

Bill 166, the Strengthening Accountability and Student Supports Act, was first tabled at the end of February. It introduces requirements surrounding mental health and anti-racism policies at colleges and universities — and would give the provincial government powers over these. It would also grant the minister authority to issue directives about costs of attending college and university.

The Council of Ontario Universities says the bill would undermine university autonomy without pledging funding for the areas in concern, while duplicating existing efforts.

Read more:

Low funding for universities puts students at risk for cycles of poverty, especially in the wake of COVID-19

As researchers concerned with equity in education, we believe this bill might increase censorship and academics’ ability to promote social justice and critical thinking on campus.

Students and other protesters are in a tent camp on the campus of Columbia University in New York on April 24, 2024.

(AP Photo/Ted Shaffrey)

Government interference concerns

Concerns about government interference within post-secondary institutions is not a new conversation. In 2018, Ontario’s Conservative government introduced a campus free speech policy.

Read more:

Campus tensions and the Mideast crisis: Will Ontario and Alberta’s ‘Chicago Principles’ on university free expression stand?

The Ontario Ministry of Colleges and Universities already holds significant power over the content of some post-secondary programs, for example, studies in early childhood education. Programs accredited by the Ministry of Training are provided with a program standard document and must adhere to this.

Jill Dunlop, Ontario Minister of Colleges and Universities, speaks during a press conference at Queen’s Park in Toronto, Feb. 26, 2024.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Arlyn McAdorey

While the proposed bill points to the importance of resources and support for students to address mental health concerns and racism on campuses, the policy is underpinned by ideas of accountability. These ideas are used to warrant sweeping government oversight of institutional policies.

The bill should be understood in a context where governments are using assessment and accountability metrics to exert influence over academic institutions.

‘Job readiness’

While universities are thought to value critical inquiry and progressive values, higher education is increasingly subsumed by corporate values. As government funding in higher education has decreased, market values of productivity and profitability have increasingly shaped expectations for universities.

Related to this is an increased focus on how higher education institutions can prepare students for the “real world” and workplace skills. This is a move away from the initial intention of universities as a place of academic inquiry and intellectual development.

The preamble to Bill 166 says “the Government of Ontario is committed to supporting a post-secondary education system that is healthy and sustainable” so students are “ready for the jobs and careers of today and tomorrow.”

These ideas of job readiness shift the purpose of higher education towards technical and trade-oriented ideas of job performance. This can have ramifications for marginalized communities who engage with academic inquiry as a form of social and political activism.

A University of Southern California protester at the campus’ Alumni Park during a protest on April 24, 2024 in Los Angeles.

(AP Photo/Richard Vogel)

What is included in ‘mental health’?

While Bill 166 might present itself as protecting students’ mental health, it is important to note that mental health is a really broad construct. It can be used to protect the worldviews of privileged majorities and prevent critical or even potentially uncomfortable conversations from entering classrooms.

However, uncomfortable conversations and dialogue are an important part of growth, uncovering biases and learning about structures of oppression. Sometimes these conversations can require deep listening. This is an important component of maintaining universities’ autonomy as places of free speech and academic inquiry.

Read more:

Middle East student dialogue: As an expert in deep conflict, what I’ve learned about making conversation possible

When we discuss mental health, it is important to consider systems of oppression, housing and job security and think about the specific experiences of marginalized people on university campuses.

Faculty and instructors who teach social justice related content in their courses are far-too-often publicly critiqued and placed at risk for emotional or even physical harm due to how the content of their courses challenges many societal assumptions.

Read more:

The stabbing attack at the University of Waterloo underscores the dangers of polarizing rhetoric about gender

Bill 166 says universities and colleges “shall have a student mental health policy that describes the programs, policies, services and supports available at the college or university in respect of student mental health” yet bypasses faculty and/or instructor mental health and well-being.

Universalized approaches can interfere

Bill 166 states that “every college and university is required to have policies and rules to address and combat racism and hate, including but not limited to anti-Indigenous racism, anti-Black racism, antisemitism and Islamophobia.”

Addressing racism and hate on campuses, including antisemitism and Islamophobia, is important.

However, universalized approaches could interfere with post-secondary institutions’ autonomy to address these issues in a fair and equitable manner. The Ontario Human Rights code already offers protection around race, ancestry, place of origin, colour, ethnic origin, citizenship and creed for staff, faculty and students on university campuses.

The Conservative Ontario government has defunded the Anti-Racism Directorate, scrapped curricular initiatives on Indigenous education, undermined the Ontario Human Rights Commission and claimed that school boards are indoctrinating children around gender identity and gender expression. The prospect of this government’s increased interference on campuses raises concern particularly for racialized and marginalized faculty, staff and students.

Effects on dissent?

Advocates like Hamilton Centre MPP Sarah Jama say government encroachment over anti-racism policies on campus would be detrimental to Black, Indigenous and other racialized students.

Such encroachment could potentially silence faculty and students who support Palestinian independence or who critique Israel’s military assault on Gaza which many experts have said is genocidal.

Democracy Now video: Jewish students suspended from Columbia University after participating in Palestinian solidarity protests participate in a ‘Seder in the Streets to Stop Arming Israel’ during the second night of Passover with journalist Naomi Klein in New York.

Increased government interference in the research and operations of publicly supported universities jeopardizes the missions of universities as places of academic freedom and inquiry. In particular, theories and knowledge from marginalized communities, such as critical race theory, are often deemed “ideological” and biased by Conservative critics.

Protestors calling for a ceasefire in Gaza demonstrate during a visit by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to the University of Victoria, in Saanich, B.C., on April 19, 2024.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

Pushback to Bill 166

The question that must be asked is: What is the purpose of university? Who is it for and who does “free speech” benefit?

If, as a society, we are maintaining the original purpose of the university as a place of free thought, inquiry and critique, then universities need to be autonomous from political interference. Läs mer…

Sexual consent has been a major focus in Australia for the past few years.

In early 2022 the federal government mandated consent education in schools. This includes information about what consent is, and how to ensure consensual relationships.

Across Australia, four states (Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland and Tasmania) and the Australian Capital Territory have now passed affirmative consent laws. While the precise wording of the laws differs between jurisdictions, affirmative consent can be defined as the need for “each individual person participating in a sexual act to take steps to say or do something to check that the other person(s) involved are consenting to a sexual activity”.

There have also been important campaigns, such as the Make No Doubt campaign in NSW, to educate about safe, pleasurable and consensual sex.

One challenge with sexual consent education is determining how it translates to real-life situations. As part of broader research seeking to answer this question, we wanted to understand how young heterosexual men and women understand and practice consent.

Our new study found that while participants mostly understood the concept of affirmative consent, they didn’t always put it into practice in the heat of the moment.

Read more:

Most states now have affirmative sexual consent laws, but not enough people know what they mean

Understanding sexual consent

Our research included a mixed group of 44 men and women aged 18 to 35, who were in relationships, dating or single. We spoke to them in focus groups and presented a variety of heterosexual sexual consent vignettes (scenarios) to discuss.

We wanted to understand how participants thought the characters should handle these situations, and how they would deal with these scenarios themselves. Scenarios were designed to be somewhat ambiguous, with no clear right answer.

An example of a vignette we used was Julia and Mark. They meet for drinks on their first date, and the chemistry is strong. They end up at Julia’s place, where she tells him she wants to take things slow and won’t be having sex that night. They start making out, and both begin to shed layers of clothing. Mark hesitates, unsure whether to continue, and Julia is uncertain how to signal her interest in other types of intimacy after setting a boundary.

Affirmative consent is now law in most Australian jurisdictions.

Anastasia Shuraeva/Pexels

Alongside the vignettes, we asked participants to share their understandings of consent, and their reflections on gender expectations around dating and sex, among other issues.

Participants demonstrated a clear understanding of consent practices in line with the affirmative consent framework. This included understanding that consent was the responsibility of all parties involved. Danny, a 23-year-old man, said:

It’s like equal responsibility in my eyes.

Participants also noted that straightforward, open communication alongside consistent verbal check-ins was important. As Abigail, a 26-year-old woman, said:

Both parties need to be actively engaging and checking boundaries as you go.

In theory versus reality

Despite appearing to understand the principles of affirmative consent, participants reacted differently when presented with varying scenarios. Instead of noting equal responsibility, most participants believed men in the scenarios were responsible for getting consent, and women providing it.

In discussing the scenarios participants highlighted the need to avoid assumptions and to encourage open communication. But this perspective shifted when discussing personal experiences and sexual consent. Here, participants expected partners to understand typical boundaries during sexual encounters, suggesting a shared sense of what’s “normal”.

In fact, participants felt following good sexual communication practices could dampen the enjoyment of sexual encounters. Some admitted that even though they knew the ideal approach, they didn’t always stick to it. As Alice, a 25-year-old woman, said:

Everything’s going well and we’re hitting it off, and then it moves into the bedroom and things just seem to flow, and I feel comfortable not having to necessarily overtly have that conversation then and there.

Lenore, a 28-year-old woman, said:

Sometimes, like, a conversation can almost kill the vibe, like if that moment is […] really hot and passionate and you’re giving them all the signals and they’re giving you all the signals, and then he was like, ‘So I want to just check in with you for a second’, I would be like, ‘Dude, come on, like, let’s just do the thing.’

Jeremy, a 34-year-old man, said:

I’ve regularly asked someone are they having a good time, you know, ‘is this okay’, ‘is this okay’, and be told, ‘No, you’ve ruined the moment’, which I found quite perplexing as someone who believes strongly in making sure there’s always consent.

There’s been an increased focus on consent education in recent years.

Mayur Gala/Unsplash

Participants also indicated affirmative consent was more important in some sexual situations over others. In discussing one of the vignettes, Lenore said:

It would really depend on what he [scenario character] tried, to be honest, like if he’s flipped me around and chucked me into a new position, like, yeah, go for it. If he’s slapped me across the face in the middle of sex without clearing that first, no. It would completely depend on what it was and the way that he goes about doing it.

Implications

Our study is relatively small and cannot be generalised to the broader Australian population. We also focused only on consent in heterosexual relationships.

Nonetheless, our research provides some insight into how young men and women may be navigating consent during sex. The results don’t imply education on sexual consent is ineffective. Rather, they highlight a significant gap between knowing and applying that knowledge.

Our findings also point to a broader and more complex issue: the need for a whole-of-society approach to rethink sexual communication and consent. One in five women have experienced sexual violence, suggesting deeper problems of masculine entitlement and societal attitudes toward women. Focusing on consent between sexual partners is one way of shifting attitudes.

Read more:

How to get consent for sex (and no, it doesn’t have to spoil the mood)

Sexual encounters often involve intricate layers of emotion and experience, influenced by culture, religion, and other factors, with elements like shame, pleasure, joy, uncertainty, fear and anxiety.

Understanding the complex variables that inform decision-making in these contexts is crucial for creating educational resources that help people navigate sexual consent in different situations. Läs mer…

There can be no more powerful symbol of the relationship between Australia and Papua New Guinea than the prime ministers of these neighbouring countries walking together on the gruelling Kokoda Track towards Isurava, high in PNG’s rugged Owen Stanley mountains.

The place where Anthony Albanese and James Marape chose to commemorate ANZAC Day was the scene of one of the toughest battles in the Pacific war, the Battle of Isurava. This is where raw Australian conscripts and militiamen fought back against an invading Japanese force in August 1942 until veteran reinforcements arrived. Their combined efforts inflicted heavy losses on the Japanese and, crucially, slowed their advance.

The Australians were supported throughout this and many other battles on the track by Papua New Guineans – the stretcher bearers who carried the wounded back to safety and the soldiers of the Papuan Infantry Battalion.

This moving collaboration has become the reference point for generations of leaders from both sides of the Torres Strait when speaking of the special relationship between the two countries. It has also inspired many Australian individuals and organisations to “give back” to PNG through financial donations and other support.

Papuan New Guinean stretcher bearers carry a wounded Australian on the Kokoda Track in 1942.

Australian War Memorial

How history informs Australia’s view of PNG

The events of 1942 had a lasting impact on Australian strategic thinking about its neighbourhood.

During the war, Australia’s lifeline to the United States across the Pacific was under direct threat from Japan’s sweep across the region. The military objective of the Japanese forces on the Kokoda Track was the capital, Port Moresby, because of its utility as a base for ongoing attacks against Australian ships and cities. For a while, an invasion of Australia itself seemed to be imminent.

The protection of Australian lines of supply and communication across the Pacific remains a central consideration in contemporary strategic thinking.

Australia’s deep sensitivity to any suggestion a potentially hostile power may be seeking to establish a naval base in the region actually predates the second world war. However, the very real threat that materialised on the Kokoda Track entrenched this view.

PNG still looms large in Australian deliberations about regional security – given its size, this wartime history and its proximity to Australia and pivotal location where Asia meets the Pacific.

Sergeant C. Ryan of Goulburn, NSW, conducts weapon training with two members of the Papuan Infantry Battalion in 1943.

Australian War Memorial

Of course, it is no longer Japan that Western strategists see as the principal strategic adversary and potential threat to stability in the Pacific. That mantle has been assumed by China, which in recent years has displayed an active interest in expanding its military links and presence in the region.

Japan has now become an important strategic ally for Australia and the United States in working to counter China’s growing influence in the Pacific, including PNG. It has made important contributions to the region’s development through aid and other economic support.

Papua New Guineans naturally have their own understanding of history, as well as today’s security environment. As Marape said last week in response to a gaffe by US President Joe Biden about his uncle having possibly been eaten by cannibals after being shot down during the second world war,

World War II was not the doing of my people. However, they were needlessly dragged into a conflict that was not their doing.

Read more:

Australia has long viewed the Pacific as a place of threats that must be contained. It’s time for this mindset to change

China’s ambitions in the region

As in other parts of the Pacific, there is no enthusiasm at all in PNG about the re-emergence of geo-strategic competition in the region. PNG leaders have joined their Pacific counterparts in emphasising climate change as the key regional security challenge and criticising their international partners for stoking tensions with China.

At the same time, there is an underlying lack of enthusiasm in PNG about expanding the country’s ties with China to include defence or policing ties.

The Marape government came under real pressure from Beijing to sign agreements covering police training and other security co-operation in the lead-up to Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit to Port Moresby last week. Ultimately, it did not do so.

Marape and his ministers have made it clear they look to Australia – not China – as their country’s key security partner.

China may have ambitions to establish a security partnership with PNG similar to the one it has signed with Solomon Islands, but it clearly has no interest in matching Australia as a development partner for the country.

Its aid spending in PNG – as in the rest of the Pacific – is very minor in comparison to Australia and may be in decline. Beijing has shown in Solomon Islands, at least, that it prefers to focus its money on nurturing relationships with members of the ruling elite.

However, China has made significant inroads as a commercial partner for PNG. Its construction firms now dominate the work taking place across the country to develop roads, bridges, public buildings and other infrastructure.

But China cannot match the breadth of the PNG relationship with Australia. This relationship encompasses social, cultural and sporting ties, as well as longstanding investment, aid and defence co-operation links.

Read more:

What do people in the Pacific really think of China? It’s more nuanced than you may imagine

‘History holds all the details’

Kokoda may have become a kind of public talisman for the Australia-PNG relationship, but there is much more to the two countries’ shared history than the wartime experience, as Marape made clear in his speech to the Australian parliament in February.

Anthony Albanese walks with James Marape after an address to parliament in February.

Lukas Coch/AAP

To make this point, he highlighted the presence in the parliamentary gallery of elderly former Australian patrol officers and their families who had dedicated their lives to the early development and administration of his country. He spoke with gratitude about the period during which Australia administered PNG – and with pride about the years since independence.

History holds all the details, for the greatest and most profound impact of the Australian administration is the democracy you left with us.

It was clear from this speech he believes Australians underestimate the depth of their own historical ties with PNG. Australians should take some comfort, in these uncertain strategic times, from the ballast these shared experiences provide for the relationship today. Läs mer…

Finding the best person to fill a position can be tough, from drafting a job ad to producing a shortlist of top interview candidates.

Employers typically consider information from several sources, including the applicant’s work history, social media presence, responses to interview questions and sometimes, psychometric testing results.

It’s also common for hiring managers to check an applicant’s references by chatting to the candidate’s nominated referees or reading over their letters of recommendations.

Reference checks tend to be the final hurdle; a sort of background check for the candidate’s job history and credentials.

Nearly every employer does reference checks, but research suggests there are important limitations worth keeping in mind.

Inconsistency can be a problem

A reliable selection method produces a consistent measure of candidate suitability. In other words, reliability enables an apples-to-apples comparison of each candidate.

But early research into reference checks found referees tend to give substantially different ratings to the same candidates.

This inconsistency is problematic because it is unclear if a favourable report reflects genuine suitability or the candidate was fortunate enough to nominate a lenient referee.

Part of the problem is employers often do not take a structured approach to obtaining information from referees.

Often referees for the same person give inconsistent assessments.

Ground Picture/Shutterstock

For instance, if asked overly general or vague questions about the candidate, each referee may focus on different aspects of past job performance or omit negative information.

Research suggests using a standardised set of questions can produce more reliable outcomes. This provides a stronger basis for making a meaningful comparison between candidates.

Unfortunately, even using a standardised assessment, referees still tend to disagree on their ratings.

This disagreement may still be worthwhile, as it can reveal important contextual differences in the candidate’s performance. For instance, one referee may have observed a candidate leading a team, while another may have only seen their project work.

However, employers still need to make sense of these different perspectives.

A reference is a poor indicator of future performance

A valid selection method is job-specific and provides useful information about how a candidate will actually perform in the role.

Reference checks are a relatively easy hurdle for candidates to overcome because referees are typically self-selected, and most job seekers can find at least one colleague who is willing to speak positively about them.

Read more:

Employers should use skill-based hiring to find hidden talent and address labour challenges

As well, a candidate’s performance in a previous position may not always be relevant for the job they are applying for.

For these reasons, reference checks show only a small correlation with employee performance in their new job.

But because of their limited ability to predict performance, employers should not rely solely on reference checks.

A mix of checks the best approach

A recent systematic review of employee selection methods suggests structured interviews, work samples, and pre-employment assessments can provide useful insights into how employees will perform.

Reviewing a candidate’s previous work can help in the hiring process.

RawPixel.com/Shutterstock

Pre-hiring assessments can reveal information about a person’s job knowledge, cognitive ability, integrity, personality, and emotional intelligence where appropriate. They are especially useful for screening numerous applicants, such as for graduate recruitment programs.

Ultimately, the job selection process should be tailored to the role requirements. For instance, if a role requires strong writing skills, this could be assessed through work samples or pre-hiring assessments.

Some candidates could be disadvantaged

A fair selection method is one that is unbiased and avoids giving weight to irrelevant information. It does not disadvantage people because of characteristics such as gender identity, age, or cultural background.

From this perspective, reference checks have several potential problems.

One is that candidates may not have access to referees of similar credibility.

For instance, a person from a high socioeconomic background is more likely to have access to senior leaders or experienced professionals in relevant fields who are willing to provide positive reports.

Reference checks may perpetuate existing inequalities.

In most cases, referees will want to provide positive reports. If the referee is a close colleague of the job applicant, they may be concerned that negative reports will be traced back to them and affect their ongoing relationship.

And employers may be motivated to offer under-performers a glowing review to get rid of them.

Read more:

6 questions you should be ready to answer to smash that job interview

Most references are difficult to verify, so referees are unlikely to suffer damage to their reputation if they talk up an average candidate, especially if the referee is outside the employer’s professional network.

In most cases a referee will want to provide a positive report.

AlexSkopje/Shutterstock

Research suggests letters of recommendation can actually disadvantage female candidates by planting doubts about their suitability.

For instance, letters about female candidates more frequently contain negativity (such as, “does not have much teaching experience”), faint praise (“needs minimal supervision”) and hedging (“has the potential to become a strong performer”).

These types of statements can lead employers to evaluate female candidates more harshly.

However, when a structured questionnaire is used, this bias does not emerge.

A flawed but worthwhile tool

While reference checks remain common, their limitations are clear. They can be unreliable, offer only moderate validity in predicting performance at best and raise fairness concerns.

However, reference checks shouldn’t be discarded. By implementing structured questioning and adopting other well-established employee selection methods, references can still be included as a final step in a robust hiring process. Läs mer…

The hyper-arid desert of Eastern Sudan, the Atbai Desert, seems like an unlikely place to find evidence of ancient cattle herders. But in this dry environment, my new research has found rock art over 4,000 years old that depicts cattle.

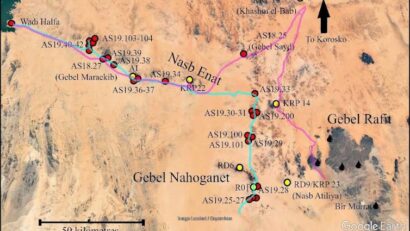

In 2018 and 2019, I led a team of archaeologists on the Atbai Survey Project. We discovered 16 new rock art sites east of the Sudanese city of Wadi Halfa, in one of the most desolate parts of the Sahara. This area receives almost no yearly rainfall.

Almost all of these rock art sites had one feature in common: the depiction of cattle, either as a lone cow or part of a larger herd.

On face value, this is a puzzling creature to find carved on desert rock walls. Cattle need plenty of water and acres of pasture, and would quickly perish today in such a sand-choked environment.

In modern Sudan, cattle only occur about 600 kilometres to the south, where the northernmost latitudes of the African monsoon create ephemeral summer grasslands suitable for cattle herding.

The theme of cattle in ancient rock art is one of most important pieces of evidence establishing a bygone age of the “green Sahara”.

New sites discovered on surveys in Eastern Sudan.

© The Atbai Survey Project

The ‘green Sahara’

Archaeological and climatic fieldwork across the entire Sahara, from Morocco to Sudan and everywhere in between, has illustrated a comprehensive picture of a region that used to be much wetter.

Climate scientists, archaeologists and geologists call this the “African humid period”. It was a time of increased summer monsoon rainfall across the continent, which began about 15,000 years ago and ended roughly 5,000 years ago.

The wastes of the Atbai Desert, north-east Sudan – a very different landscape to the ‘green Sahara’.

Julien Cooper

This “green Sahara” is a vital period in human history. In North Africa, this was when agriculture began and livestock were domesticated.

In this small “wet gap”, around 8,000–7,000 years ago, local nomads adopted cattle and other livestock such as sheep and goats from their neighbours to the north in Egypt and the Middle East.

Read more:

The Sahara Desert used to be a green savannah – new research explains why

A close human-animal connection

When the prehistoric artists painted cattle on their rock canvasses in what is now Sudan, the desert was a grassy savannah. It was brimming with pools, rivers, swamps and waterholes and typical African game such as elephants, rhinos and cheetah – very different to the deserts of today.

Cattle were not just a source of meat and milk. Close inspection of the rock art and in the archaeological record reveals these animals were modified by their owners. Horns were deformed, skin decorated and artificial folds fashioned on their neck, so-called “pendants”.

A strong relationship between human and animal: a cow with a modified ‘neck’ pendant and horns.

Julien Cooper

Cattle were even buried alongside humans in massive cemeteries, signalling an intimate link between person, animal and group identity.

The perils of climate change

At the end of the “humid period”, around 3000 BCE, things began to worsen rapidly. Lakes and rivers dried up and sands swallowed dead pastures. Scientists debate how rapidly conditions worsened, and this seems to have differed greatly across specific subregions.

Local human populations had a choice – leave the desert or adapt to their new dry norms. For those that left the Sahara for wetter parts, the best refuge was the Nile. It is no accident that this rough period also eventuated in the rise of urban agricultural civilisations in Egypt and Sudan.

The most common image in the local rock art was of cattle.

Julien Cooper

Some of the deserts, such as the Atbai Desert around Wadi Halfa where the rock art was discovered, became almost depopulated. Not even the hardiest of livestock could survive in such regions. For those who remained, cattle were abandoned for hardier sheep and goats (the camel would not be domesticated in North Africa for another 2,000–3,000 years).

This abandonment would have major ramifications on all aspects of human life: diet and lack of milk, migratory patterns of herding families and, for nomads so connected to their cattle, their very identity and ideology.

New phases of history

Archaeologists, who spend so much time on the ancient artefacts of the past, often forget our ancestors had emotions. They lived, loved and suffered just like we do. Abandoning an animal that was very much a core part of their identity, and with whom they shared an emotional connection, cannot have been easy for their emotions and sense of place in the world.

For those communities that migrated and lived on the Nile, cattle continued to be a symbol of identity and importance. At the ancient capital of Sudan, Kerma, community leaders were buried in elaborate graves girded by cattle skulls. One burial even had 4,899 skulls.

Today in South Sudan and much of the Horn of Africa, similar practices regarding cattle and their cultural prominence endure to the present. Here, just as in ancient Sahara, cattle are decorated, branded and have an important place in funeral traditions, with cattle skulls marking graves and cattle consumed in feasts.

As we move into a new phase of human history subject to rapid climate oscillations and environmental degradation, we need to ponder just how we will adapt beyond questions of economy and subsistence.

One of the most basic common denominators of culture is our relationship to our shared landscape. Environmental change, whether we like it or not, will force us to create new identities, symbols and meanings.

Read more:

Innovations on the Nile over millennia offer lessons in engineering sustainable futures Läs mer…

Over the last 25 years, the ozone hole which forming over Antarctica each spring has started to shrink.

But over the last four years, even as the hole has shrunk it has persisted for an unusually long time. Our new research found that instead of closing up during November it has stayed open well into December. This is early summer – the crucial period of new plant growth in coastal Antarctica and the peak breeding season for penguins and seals.

That’s a worry. When the ozone hole forms, more ultraviolet rays get through the atmosphere. And while penguins and seals have protective covering, their young may be more vulnerable.

Why does ozone matter?

Over the past half century, we damaged the earth’s protective ozone layer by using chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and related chemicals. Thanks to coordinated global action these chemicals are now banned.

Because CFCs have long lifetimes, it will be decades before they are completely removed from the atmosphere. As a result, we still see the ozone hole forming each year.

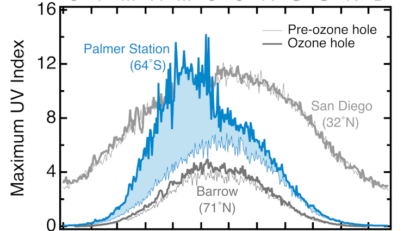

The lion’s share of ozone damage happens over Antarctica. When the hole forms, the UV index doubles, reaching extreme levels. We might expect to see UV days over 14 in summers in Australia or California, but not in polar regions.

This figure shows the maximum UV index at Palmer Station in Antarctica each month, in both ozone hole (thick blue line) and normal (thin blue line) conditions. This is compared with an equivalent location in the Arctic (Barrow, Alaska) as well as a Californian location (San Diego). The blue area shows how the UV index has more than doubled in the ozone hole era.

Bernhard et al 2022

Luckily, on land most species are dormant and protected under snow when the ozone hole opens in early spring (September to November). Marine life is protected by sea ice cover and Antarctica’s moss forests are under snow. These protective icy covers have helped to protect most life in Antarctica from ozone depletion – until now.

Read more:

Photos from the field: spying on Antarctic moss using drones, MossCam, smart sensors and AI

Unusually long-lived ozone holes

A series of unusual events between 2020 and 2023 saw the ozone hole persist into December. The record-breaking 2019–2020 Australian bushfires, the huge underwater volcanic eruption off Tonga, and three consecutive years of La Niña. Volcanoes and bushfires can inject ash and smoke into the stratosphere. Chemical reactions occurring on the surface of these tiny particulates can destroy ozone.

Read more:

La Niña is finishing an extremely unusual three-year cycle – here’s how it affected weather around the world

These longer-lasting ozone holes coincided with significant loss of sea ice, which meant many animals and plants would have had fewer places to hide.

You can see how the size of the ozone hole in 2019 (top left) and 2020 (top right) differs from the mean ozone hole area between 1979 and 2018. Maps of ozone area for September to December show how the ozone hole disappeared early in 2019 (November, middle panel) but extended into December in 2020 (lower panel)

NASA Ozone Watch, CC BY-NC-ND

What does stronger UV radiation do to ecosystems?

If ozone holes last longer, summer-breeding animals around Antarctica’s vast coastline will be exposed to high levels of reflected UV radiation. More UV can get through, and ice and snow is highly reflective, bouncing these rays around.

In humans, high UV exposure increases our risk of skin cancer and cataracts. But we don’t have fur or feathers. While penguins and seals have skin protection, their eyes aren’t protected.

Is it doing damage? We don’t know for sure. Very few studies report on what UV radiation does to animals in Antarctica. Most are done in zoos, where researchers study what happens when animals are kept under artificial light.

Even so, it is a concern. More UV radiation in early summer could be particularly damaging to young animals, such as penguin chicks and seal pups who hatch or are born in late spring.

As plants such as Antarctic hairgrass, Deschampsia antarctica, the cushion plant, Colobanthus quitensis and lots of mosses emerge from under snow in late spring, they will be exposed to maximum UV levels.

Antarctic mosses actually produce their own sunscreen to protect themselves from UV radiation, but this comes at the cost of reduced growth.

Trillions of tiny phytoplankton live under the sea ice. These microscopic floating algae also make sunscreen compounds, called microsporine amino acids.

What about marine creatures? Krill will dive deeper into the water column if the UV radiation is too high, while fish eggs usually have melanin, the same protective compound as humans, though not all fish life stages are as well protected.

If the ozone hole peaks in October, most Antarctic wildlife is protected by snow or sea ice cover which helps reflect the UV rays (top panel). But if the ozone hole persists into December (lower panel) the snow and ice will have melted, and more animals and plants are present and exposed to UV.

Global Change Biology

Four of the past five years have seen sea ice extent reduce, a direct consequence of climate change.

Less sea ice means more UV light can penetrate the ocean, where it makes it harder for Antarctic phytoplankton and krill to survive. Much relies on these tiny creatures, who form the base of the food web. If they find it harder to survive, hunger will ripple up the food chain. Antarctica’s waters are also getting warmer and more acidic due to climate change.

An uncertain outlook for Antarctica

We should, by rights, be celebrating the success of banning CFCS – a rare example of fixing an environmental problem. But that might be premature. Climate change may be delaying the recovery of our ozone layer by, for example, making bushfires more common and more severe.

Ozone could also suffer from geoengineering proposals such as spraying sulphates into the atmosphere to reflect sunlight, as well as more frequent rocket launches.

If the recent trend continues, and the ozone hole lingers into the summer, we can expect to see more damage done to plants and animals – compounded by other threats.

We don’t know if the longer-lasting ozone hole will continue. But we do know climate change is causing the atmosphere to behave in unprecedented ways. To keep ozone recovery on track, we need to take immediate action to reduce the carbon we emit into the atmosphere.

Read more:

Antarctica’s sea ice hit another low this year – understanding how ocean warming is driving the loss is key Läs mer…