Kakapåkaka kaka

En ny klassiker kan man kalla det. Jag tog två kakor och slog ihop till en. I botten är det mördeg och ovanpå en havrekaka. Det blev en av mina favoritkakor. Lätta att göra är de också. Recept Ugnstemperatur 175 Läs mer…

Nyheter och länkar - en bra startsida helt enkelt |Oculus lyx vitae

En ny klassiker kan man kalla det. Jag tog två kakor och slog ihop till en. I botten är det mördeg och ovanpå en havrekaka. Det blev en av mina favoritkakor. Lätta att göra är de också. Recept Ugnstemperatur 175 Läs mer…

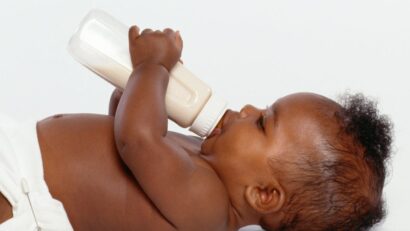

Nestlé has been criticised for adding sugar and honey to infant milk and cereal products sold in many poorer countries. The Swiss food giant controls 20% of the baby-food market, valued at nearly US$70 billion.

Nadine Dreyer asked public health academic Susan Goldstein why extra sugar is particularly bad for babies and why she thinks multinationals target low-income countries with sweeter products.

Why has Nestlé been criticised?

Public Eye, a Swiss investigative organisation, sent samples of Nestlé baby-food products sold in Asia, Africa and Latin America to a Belgian laboratory for testing. The laboratory found in many cases that baby formula with no added sugar sold in Switzerland, Germany, France and the UK contained unhealthy levels of sugar when sold in countries such as the Philippines, South Africa and Thailand.

As the Public Eye investigation revealed, one example of this is Nestlé’s biscuit-flavoured cereals for babies aged six months and older: in Senegal and South Africa they contain 6g of added sugar. In Switzerland, where Nestlé is based, the same product has none.

In South Africa, Nestlé promotes its wheat cereal Cerelac as a source of 12 essential vitamins and minerals under the theme “little bodies need big support”. Yet all Cerelac products sold in this country contain high levels of added sugar.

Obesity is increasingly a problem in low- and middle-income countries. In Africa, the number of overweight children under five has increased by nearly 23% since 2000.

The World Health Organization has called for a ban on added sugar in products for babies and young children under three years of age.

Why is extra sugar particularly unhealthy for babies?

Adding sugar make the foods delicious and, some argue, addictive. The same goes for adding salt and fat to products.

Children shouldn’t eat any added sugar before they turn two. Studies show that adding sugar to any food for babies or small children predisposes them to having a sweet tooth. They start preferring sweet things, which is harmful in their diets throughout their lives.

Unnecessary sugar contributes to obesity, which has major health effects such as diabetes, high blood pressure and other cardiovascular diseases, cancer and joint problems among others.

The rate of overweight children in South Africa is 13%, twice the global average of 6.1%.

These extra sugars, fats and salt are harmful to our health throughout our lifetime, but especially to babies as they are still building their bodies.

Children eat relatively small amounts of food at this stage. To ensure healthy nutrition, the food they eat must be high in nutrients.

Read more:

How South African food companies go about shaping public health policy in their favour

How do multinationals influence health policies?

Companies commonly influence public health through lobbying and party donations. This gives politicians and political parties an incentive to align decisions with commercial agendas.

Low- and middle-income countries often have to address potential trade-offs: potential economic growth from an expanding commercial base and potential harms from the same commercial forces.

Research into how South African food companies, particularly large transnationals, go about shaping public health policy in their favour found 107 examples of food industry practices designed to influence public health policy.

In many cases companies promise financial support in areas such as funding research. In 2023 a South African food security research centre attached to a university signed a memorandum of understanding with Nestlé signalling their intent to “forge a transformative partnership” to shape “the future of food and nutrition research and education” and transform “Africa’s food systems”.

What happens in high-income countries?

Most high-income countries have clear guidelines about baby foods. One example is the EU directive on processed cereal-based foods and baby foods for infants and young children.

Another is the Swiss Nutrition Policy, which sets out clear guidelines on healthy eating and advertising aimed at children.

The global food system is coming under scrutiny not just for health reasons but for the humane treatment of animals, genetically engineered foods, and social and environmental justice.

What should governments in developing countries be doing?

South Africa already has limits on salt content but we need limits on added sugar and oil.

Taxing baby foods as we do sugary beverages is another way of discouraging these harmful additions.

We need to make sure that consumers are aware of what’s in their food by having large front-of-package warning labels. Take yogurt: many people assume it is healthy, but there is lots of added sugar in many brands.

Read more:

Bad food choices: clearer labels aim to help South Africans pick healthier options

Consumers should be calling for front-of-pack labels that the Department of Health has proposed so that parents can easily identify unhealthy foods. Läs mer…

Australia’s inflation rate has fallen for the fifth successive quarter, and it’s now less than half of what it was back in late 2022.

The annual rate peaked at 7.8% in the December quarter of 2022 and is now just 3.6%, in the March quarter figures released on Wednesday, leaving it within spitting distance of the Reserve Bank’s 2–3% target.

But it’s too early for mortgage holders to celebrate.

On Wednesday Westpac noted the pace of improvement was slowing and pushed out its forecast of when the Reserve Bank would begin cutting rates from September this year to November.

The monthly measure of annual inflation also released on Wednesday rose marginally from 3.4% in February to 3.5% in March.

While some may see this as suggesting that the “last mile” of bringing inflation to heel might be difficult, not too much should be read into it.

The monthly series is

experimental and volatile. As the chart shows, it has twice given a false impression that inflation was rising again over the past year.

Australia is in good company. While inflation has fallen throughout the developed world since late 2022, in recent months the improvements have slowed.

In the US, inflation is edging up.

US Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell says it might take “longer than expected” for them to be sure inflation has fallen low enough to begin cutting rates.

Other banks might cut rates first. The head of the European Central Bank Christine Lagarde said she was “data-dependent, not Fed-dependent”.

In Australia, as in much of the rest of the world, inflation in the price of goods has come down faster than inflation in the price of services.

But the figures released on Wednesday show inflation in the price of services continuing to fall, although more slowly over the March quarter.

Rents climbed a further 2.1% in the quarter, to be up 7.8% over the year.

The measure reported is out-of-pocket rents, net of rental assistance. The Bureau of Statistics said had it not been for the increases in rent assistance announced in last year’s May budget, it would have recorded an increase in rents of 9.5%

In a report released with the consumer price index, the Bureau noted that renters’ experiences were not uniform and that many received rent reductions during COVID.

One in five city renters continued to pay less rent than before the pandemic.

Price falls for electricity (due to government rebates) and clothing in the March quarter helped lower annual inflation.

But sharp rises in the prices of insurance (a response to natural disasters) as well as education and pharmaceuticals made the task harder.

There might have also been a Taylor Swift effect. Prices for restaurant meals, urban transport, domestic accommodation and “other recreational and cultural services” rose more strongly in Sydney and Melbourne, where she played concerts in February, than in Brisbane and Perth where she did not.

What will it mean for student debt?

While interest is not charged on the debt accumulated by students as part of their student loans, the amount owed increases every June in line with the March quarter consumer price index.

The formula is complicated, although easy to calculate.

Today’s figures produce an increase of 4.7499517% – a figure slightly closer to 4.7% than 4.8%, meaning it rounds down to 4.7%.

However, one interpretation of rules suggests it might be rounded up, to 4.8%.

Regardless, the increase due in June will be substantial, on top of an already outsized increase of 7.1% in June last year.

There’s a chance the increase won’t be either of these figures. The government promised an announcement about the scheme before the May budget.

The Reserve Bank will update its inflation and other economic forecasts one week before the May budget on May 7. Treasurer Jim Chalmers will hand down the budget on May 14. Läs mer…

Just when we think the price of rentals could not get any worse, this week’s Rental Affordability Snapshot by Anglicare has revealed low-income Australians are facing a housing crisis like never before.

In fact, if you rely on the Youth Allowance, there is not a single rental property across Australia you can afford this week.

How did rental affordability get this bad?

Several post-COVID factors have been blamed, including our preference for more space, the return of international migrants, and rising interest rates.

However, the rental affordability crisis pre-dates COVID.

Affordability has been steadily declining for decades, as successive governments have failed to make shelter more affordable for low-to-moderate income Australians.

The market is getting squeezed at both ends

At the lower end of the rental sector, the growth in the supply of social housing persistently lags behind demand, trending at under one-third the rate of population growth.

This has forced growing numbers of low-income Australians to seek shelter in the private rental sector, where they face intense competition from higher-income renters.

At the upper end, more and more aspiring home buyers are getting locked out of home ownership.

Read more:

Many Australians face losing their homes right now. Here’s how the government should help

A recent study found more households with higher incomes are now renting.

Households earning $140,000 a year or more (in 2021 dollars) accounted for just 8% of private renters in 1996. By 2021, this tripled to 24%. No doubt, this crowds out lower-income households who are now facing a shortage of affordable homes to rent.

Why current policies are not working

Worsening affordability in the private rental sector highlights a housing system that is broken. Current policies just aren’t working.

While current policies focus on supply, more work is needed including fixing labour shortages and providing greater stock diversity.

The planning system plays a critical role and zoning rules can be reformed to support the supply of more affordable options.

Zoning rules can be used to create more affordable housing.

doublelee/Shutterstock

However, the housing affordability challenge is not solely a supply problem. There is also a need to respond to the super-charged demand in the property market.

An overheated market will undoubtedly place intense pressure on the rental sector because aspiring first home buyers are forced to rent for longer, as house prices soar at a rate unmatched by their wages.

Yet, governments continue to resist calls for winding back the generous tax concessions enjoyed by multi-property owners.

The main help available to low-income private renters – the Commonwealth Rent Assistance scheme – is poorly targeted with nearly one in five low-income renters deemed ineligible, while another one in four receive it despite not being in rental stress.

Can affordable housing occur naturally?

Some commentators support the theory of filtering – a market-based process by which the supply of new dwellings in more expensive segments creates additional supply of dwellings for low-income households as high-income earners vacate their former dwellings.

Proponents of filtering argue building more housing anywhere – even in wealthier ends of the property market – will eventually improve affordability across the board because lower priced housing will trickle down to the poorest households.

However, the persistent affordability crisis low-income households face and the rise in homelessness are crucial signs filtering does not work well and cannot be relied upon to produce lower cost housing.

Location, location, location

Location does matter, if we expect building new housing to work for low-income individuals.

What is needed is a steady increase of affordable, quality housing in areas offering low-income renters the same access to jobs and amenities as higher-income households.

Any new housing needs to be well located as well as reasonably priced.

Duncan Andison/Shutterstock

The National Housing Accord aims to deliver 1.2 million new dwellings over five years from mid-2024. But it must ensure these are “well-located” for people who need affordable housing, as suggested in the accord.

Recent modelling shows unaffordable housing and poor neighbourhoods both negatively affect mental health, reinforcing the need to provide both affordable and well-located housing.

The upcoming budget

While the 15% increase in the maximum rent assistance rate was welcomed in the last budget, the program is long overdue for a major restructure to target those in rental stress.

Also, tax concessions on second properties should be wound back to reduce competition for those struggling to buy their first home. This would eventually help ease affordability pressures on low-income renters as more higher-income renters shift into homeownership.

Read more:

A prefab building revolution can help resolve both the climate and housing crises

The potential negative impacts on rental supply can be mitigated by careful design of tax and other changes that guard against market destabilisation concerns.

Overall, housing affordability solutions have to be multi-faceted. The housing system is badly broken and meaningful repair cannot be achieved unless policymakers are willing to confront both supply and demand challenges. Läs mer…

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains names and images of deceased people, as well as sensitive historical information related to Indigenous war service.

Since the 1860s, thousands of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have served in the Australian Defence Force. They have fought in every major war from the Boer War to Afghanistan. More than 1,000 Aboriginal and Torres Islanders served in the first world war, with at least 70 stationed on the front lines and in the trenches at Gallipoli.

At the outbreak of WWI, the 1910 amendment to the Australian Defence Act of 1903 prevented persons “not substantially of European origin or descent” from enlisting. In addition, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders weren’t yet considered Australian citizens and were therefore automatically excluded from enlisting.

Despite this, many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders answered the call to defend their country by hiding their racial identity to enlist.

This Anzac Day, we can point to many examples of mainstream media projects, both fiction and non-fiction, dedicated to the Australian experience of WWI. But within these stories is a striking lack of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people or characters that represent the wartime sacrifices made by First Nations peoples.

Why have their contributions been erased? And when will they be remembered?

Fighting for Country

Serving on the ground, in the air and on the sea, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people entered the war effort for several reasons.

The propaganda that encouraged white Australians to enlist in search of travel and adventure also reached Aboriginal reserves and communities, having a similar impact. The chance to earn a wage and gain an education were also attractive causes as these rights were heavily restricted for Indigenous Australians at the time.

For the most part, however, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who joined the war effort did so out of a deep love for their country. As the Australian War Memorial’s first Indigenous liaison officer, Gary Oakley, explains:

They had that warrior spirit and they wanted to prove themselves.

These men were willing to fight for their country’s freedom alongside countrymen who were not willing to fight for their freedom. Their loyalty to the land, and responsibility to protect it, were too powerful to ignore.

Yet, once the war ended, they returned to as much discrimination (if not more) than before it began. Any hopes of equal treatment by the Australian government and white society on account of their service were quickly dashed.

Returned Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander soldiers were denied the recognition and support schemes provided to their non-Indigenous comrades. Even today, many families and communities continue to seek due recognition for Indigenous peoples’ contributions to the war effort.

This 1917 photo in Beersheba, Palestine, is said to show men and horses from the 11th Australian Light Horse Brigade, the day after the Allied forces charged Beersheba and captured the town from the Turks.

Australian War Memorial/Donor N. MacDonald

Read more:

Telling the forgotten stories of Indigenous servicemen in the first world war

(A lack of) Indigenous recognition in media

Indigenous people’s contributions during WWI continue to be left out of major mainstream media productions. Before Dawn (2024), the most recent Australian film based on the war, fails to include a single Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person in its cast.

This trend continues in Beneath Hill 60 (2010), Ghosts of War (2010), Forbidden Ground (2013), An Accidental Hero (2013), William Kelly’s War (2014) and Water Diviner (2014). Earlier films such as The Lighthorsemen (1987) and Gallipoli (1981) – perhaps the most iconic Australian WWI film – also fails to include or even mention an Indigenous presence.

And there was indeed a presence. Consider James Lingwoodock, a Kabi Kabi from Queensland.

A renowned horseman, Lingwoodock joined the 11th Light Horse Regiment and fought in (and survived) the 1917 Battle of Beersheba – a significant victory for Australia. He returned to Australia in 1919.

The double wedding party of 11th Light Horse Regiment members James Lingwoodock (left) and John Geary (fourth from left), along with Daisy Lingwoodock (nee Roberts) (second from left), an unidentified woman, the Reverend W.P.B. Miles (second from right) and Alice Geary (nee Bond) (right).

State Library of Queensland

Consider also the four Noongar brothers from the township of Katanning, Western Australia, who entered the battlefields of WWI. Lewis and Larry Farmer both fought and survived at Gallipoli, but Larry was later killed on the Western Front. A third brother, Augustus Pegg Farmer – the first Aboriginal soldier awarded the Military Medal for bravery – was killed in action several months later.

Lewis eventually made it home to Katanning, along with the fourth brother, Kenneth.

Kenneth Farmer (top left), Pegg Farmer (bottom left), Larry Farmer (top right) and Lewis Farmer (bottom right) pictured in a 1916 edition of the Sunday Times.

Trove

Untold stories

There have been some film and television projects dedicated to the Australian Frontier Wars, which were fought between First Nations peoples and the first waves of British invaders. Two examples are the documentary The Australian Wars (2022) and the film Higher Ground (2020).

Similarly, the Australian War Memorial collection includes Indigenous-produced documentaries and short films that capture the varied experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander servicemen and women. But it’s fair to say such projects sit outside the popular media most Australians are exposed to.

James Lingwoodock pictured in The Queenslander Pictorial in 1917.

State Library of Queensland

We need more collaborations that will bring Indigenous wartime stories to mainstream audiences, while retaining their cultural integrity. We also need to ensure Indigenous ownership and control over these stories.

Where is the onscreen tale of the Indigenous Anzac soldier who obscured his racial identity to enlist? The solider who risked life and limb for Country? Who survived through horrors, only to be excluded from all forms of post-war recognition and compensation? Whose traditional land was portioned up and gifted to returned white soldiers? Who struggled with post-war trauma in silence and isolation and who died without being acknowledged?

These stories, along with a great many others, are waiting to be told. The Indigenous persons who served in WWI, and their descendants, deserve to have them heard – just as all Australians deserve the opportunity to hear them.

I would like to sincerely acknowledge the diverse traditional custodians of this great land – their respective communities, Elders and Countries. I particularly acknowledge the Binjarub, Noongar nation, peoples and Country where I reside. I acknowledge the collective contributions, past and present, and pay my deepest respects to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander service peoples for their courage and sacrifices: an ongoing source of strength and pride for us all. Läs mer…

Victor Farr, a private in the 1st Infantry Battalion, was among the first to land at Anzac Cove just before dawn on April 25 1915.

Victor Farr was 20 when he died.

© Commonwealth of Australia (National Archives of Australia) 2024, CC BY-NC-ND

In the chaos, Farr went missing. When the first roll call was conducted on April 29, he was nowhere to be found. His record was amended to read “missing”, something guaranteed to send any parent into a blind panic.

It was not until January 1916 that it was determined Farr had been killed in action in Turkey sometime between April 25 and 29. He was 20 years old when he died.

His mother, Mary Drummond, had spent months in agony waiting for any news of her only child. Her initial deference to authorities gave way to an increasingly desperate and angry correspondence. She wrote:

Now Sir, I think it is your duty […] when a mother gives her son […] when that son is wounded, she ought to have some news.

By October, she tried to enlist the help of her local member of parliament, imploring him to find out if her son was alive.

But it was not until 1921, six years after Farr was last seen alive, that the army conceded exhaustive enquiries had failed to locate his body. She replied:

I only wish you could tell me if you knew he was buried, my sorrow would not be so great.

Farr’s name is etched on a panel at the Lone Pine Memorial to the Missing at Gallipoli, along with more than 4,900 of his Australian comrades who likewise have no known grave.

Read more:

How Anzac Day came to occupy a sacred place in Australians’ hearts

A heavy price

Almost half of the eligible white, male population of Australia volunteered and enlisted in the First Australian Imperial Force between 1914 and 1918.

Of the 416,000 who joined up, more than 330,000 men served overseas. Of these, more than 60,000 would never return. These are among the highest casualty figures for any combatant nation in the entire war.

More than 60,000 Australian men would never return.

Leslie Hore/Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Over 80% of Australia’s soldiers were unmarried, like Farr; in some rural communities, that rate was about 95%. So the burden of bereavement fell on the shoulders of ageing parents.

The impact of wartime bereavement on ageing parents was enormous. For some, grief became the primary motif for the rest of their days. For most, the memory haunted them into the post-war years, and for all, the war became the pivotal event of their lives, after which nothing would ever be the same.

Read more:

Women have been neglected by the Anzac tradition, and it’s time that changed

Some ended up in mental hospitals

The physical health of many parents declined rapidly when they heard their son had died. One example was Katherine Blair. She died unexpectedly at the age of 54 from heart failure on the first anniversary of her son’s death in France.

There was evidence of mothers and fathers becoming violent, thinking about suicide, causing public disturbances, and turning to alcohol in their distress.

As I outlined in my PhD thesis, many working class mothers and fathers joined the wards of public mental hospitals, such as Callan Park in Sydney. Some stayed there for the rest of their lives.

Many grieving parents ended up in public mental hospitals, such as Sydney’s Callan Park.

Adam.J.W.C. / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

The psychiatric files I examined from several major mental hospitals showed evidence of delusions, fantasies and complete denial about their son’s death. Some had lost more than one son.

Upper class families avoided the stigma of public mental hospitals, as they could afford to see private doctors, and have nursing assistance at home.

Upper class fathers, in particular, appointed themselves as guardians of their son’s memory. They spent an inordinate amount of time, effort and funds on lobbying the Australian government for recognition of their son’s service, and producing elaborate memory books and commemorative artefacts. Perhaps this was a sign of obsessive grief, but one not available to working class families.

Read more:

Telling the forgotten stories of Indigenous servicemen in the first world war

How mourning changed

Death and injury during the war touched every part of the country, from cities to hamlets, from towns to stations.

The scale of loss was as shocking as it was unprecedented, and permanently changed the culture of mourning practices in Australia.

Funeral services and overt displays of mourning differed according to class. Overall, however, the Australian experience of death in the 19th century was based on traditions embraced in Victorian England – deathbed attendance, the graveside funeral service, the headstone and its inscription, and the physical act of visiting the grave to place flowers or other mementos on special occasions.

There was also the practice of wearing mourning black and for wealthier families, ornate funeral processions through the streets with plumed horses to demonstrate the social standing and piety of the deceased.

In the early 1900s, funeral processions like this were elaborate affairs. But funerals soon changed.

Aussie~mobs/Flickr

However, two realities were required to mourn within the comfort of these familiar rituals – the knowledge of how and where their loved one had died, and the presence of the body.

Neither was available to the bereaved in Australia during the Great War. These established, reliable patterns had been stripped away.

Read more:

Friday essay: images of mourning and the power of acknowledging grief

Instead, and with so many who were bereaved, the notion of claiming loss in public was seen as tasteless and vulgar.

Rather than funerals being ostentatious public displays, they became private affairs for family and close friends.

Grief was endured and expressed within the privacy of the home, with a performance of dignified stoicism in public. The practice of wearing mourning black fell out of style.

An estimated 4,000-5,000 war memorials were built across the country. These became the focal point for communities to honour their dead and remember their sacrifice, a practice we still see on Anzac Day today. Läs mer…

Most of us have been stung by a bee and we know it’s not much fun. But maybe we also felt a tinge of regret, or vindication, knowing the offending bee will die. Right? Well, for 99.96% of bee species, that’s not actually the case.

Only eight out of almost 21,000 bee species in the world die when they sting. Another subset can’t sting at all, and the majority of bees can sting as often as they want. But there’s even more to it than that.

To understand the intricacies of bees and their stinging potential, we’re going to need to talk about the shape of stingers, bee genitals, and attitude.

Our beloved, and deadly, honey bees

What you most likely remember getting stung by is the European honey bee (Apis mellifera). Native to Europe and Africa, these bees are today found almost everywhere in the world.

They are one of eight honey bee species worldwide, with Apis bees representing just 0.04% of total bee species. And yes, these bees die after they sting you.

But why?

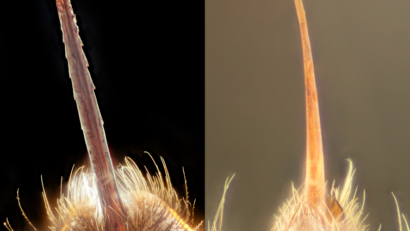

We could say they die for queen and colony, but the actual reason these bees die after stinging is because of their barbed stingers. These brutal barbs will, most of the time, prevent the bee from pulling the stinger out.

The European honeybee has a barbed stinger (left), while a native Fijian bee’s stinger is unbarbed (right).

Sam Droege (left) / James Dorey (right)

Instead, the bee leaves her appendage embedded in your skin and flies off without it. After the bee is gone, to later die from her wound, the stinger remains lodged there pumping more venom.

Beyond that, bees and wasps (probably mostly European honey bees) are Australia’s deadliest venomous animals. In 2017–18, 12 out of 19 deaths due to venomous animals were because of these little insects. (Only a small proportion of people are deathly allergic.)

Talk about good PR.

So what is a stinger?

A stinger, at least in most bees, wasps and ants, is actually a tube for laying eggs (ovipositor) that has also been adapted for violent defence. This group of stinging insects, the aculeate wasps (yes, bees and ants are technically a kind of wasp), have been stabbing away in self-defence for 190 million years.

You could say it’s their defining feature.

A Sycoscapter parasitoid wasp laying eggs into a fig through her ovipositor (bottom middle). Her ovipositor sheath, which usually surrounds the ovipositor, is curved behind her and to the right. Sycoscapter wasps are sister to the aculeate wasps (they don’t sting).

James Dorey Photography

With so much evolution literally under their belts they’ve also developed a diversity of stinging strategies. But let’s just get back to the bees.

The sting of the European honey bee is about as painful as a bee sting gets, scoring a 2 out of 4 on the Schmidt insect sting pain index.

But most other bees don’t pack the same punch — though I have heard some painful reviews from less-than-careful colleagues. On the flipside, most bee species can sting you as many times as they like because their stingers lack the barbs found in honey bees. Although, if they keep at it, they might eventually run out of venom.

Even more surprising is that hundreds of bee species have lost their ability to sting entirely.

Can you tell who’s packing?

Globally, there are 537 species (about 2.6% of all bee species) of “stingless bees” in the tribe Meliponini. We have only 11 of these species (in the genera Austroplebeia and Tetragonula) in Australia. These peaceful little bees can also be kept in hives and make honey.

Stingless bees can still defend their nests, when offended, by biting. But you might think of them more as a nuisance than a deadly stinging swarm.

An Australian stingless bee, Tetragonula carbonaria, foraging on a Macadamia flower.

James Dorey Photography

Australia also has the only bee family (there are a total of seven families globally) that’s found on a single continent. This is the Stenotritidae family, which comprises 21 species. These gentle and gorgeous giants (14–19mm in length, up to twice as long as European honey bees) also get around without a functional stinger.

The long ovipositor of this parasitoid, and non-stinging, wasp is essentially a hypodermic needle for injecting an egg.

James Dorey Photography

The astute reader might have realised something by this point in the article. If stingers are modified egg-laying tubes … what about the boys? Male bees, of all bee species, lack stingers and have, ahem, other anatomy instead. However, some male bees will still make a show of “stinging” if you try to grab them.

Some male wasps can even do a bit of damage, though they have no venom to produce a sting.

Why is it always the honey bees?

So, if the majority of bees can sting, why is it always the European honey bee having a go? There are a couple of likely answers to that question.

First, the European honey bee is very abundant across much of the world. Their colonies typically have around 50,000 individuals and they can fly 10km to forage.

Read more:

Help, bees have colonised the walls of my house! Why are they there and what should I do?

In comparison, most wild bees only forage very short distances (less than 200m) and must stay close to their nest. So those hardworking European honey bees are really putting in the miles.

Second, European honey bees are social. They will literally die to protect their mother, sisters and brothers. In contrast, the vast majority of bees (and wasps) are actually solitary (single mums doing it for themselves) and lack the altruistic aggression of their social relatives.

A complicated relationship

We have an interesting relationship with our European honey bees. They can be deadly, are non-native (across much of the world), and will aggressively defend their nests. But they are crucial for crop pollination and, well, their honey is to die for.

But it’s worth remembering these are the tiny minority in terms of species. We have thousands of native bee species (more than 1,600 found so far in Australia) that are more likely to simply buzz off than go in for a sting. Läs mer…

I had the good fortune to care for the sugar gum at The University of Melbourne’s Burnley Gardens in Victoria where I worked for many decades. It was a fine tree – tall and dominating. Less than a year after my retirement, it shed a couple of major limbs and was removed. I had been its custodian for over 20 years and took my responsibility seriously, extending its useful life.

I loved that tree. But not everyone feels the same way about sugar gums (Eucalyptus cladocalyx), thanks to the fact many have multiple spindly trunks or branches that sometimes drop when they haven’t been managed well.

The truth is, Eucalyptus cladocalyx is a hardy and versatile native tree of South Australia which grows very nicely in other parts of the country. They were once widely planted across south-eastern Australia and they have grown in Western Australia too. In many places they defined the roadside vegetation of the region.

Many are gone now; lost to storms, old age, road works and safety concerns as agricultural land becomes treeless outer suburbs. It’s a shame, because there is much to appreciate and admire about the sugar gum.

They do drop branches when they haven’t been managed well.

Gregory Moore

Read more:

Hard to kill: here’s why eucalypts are survival experts

A hardy and impressive tree

In its natural habitat in the Flinders Ranges, sugar gum can be an impressive single-trunked tree. It can grow up to 35 metres or more in height, with a girth of up to four and a half metres (although those on the Eyre Peninsula and Kangaroo Island tend to be smaller).

The name “sugar gum” arises from its apparently sweet leaves, but benefit from my experience and don’t put it to the test.

I have found the bark can be sweet – but I can’t say I recommend trying that for yourself, either. The sap of cider gum, Eucalyptus gunnii, on the other hand, is sweet and can be fermented.

Like many eucalypts, sugar gum is a hardy tree with plenty of dormant buds (epicormic buds) under its smooth yellow, grey bark.

When the tree is damaged by fire or stressed, these buds may become active and produce lots of new shoots. This is how some trees renew themselves after damage from fire, grazing, flooding, storms or poor pruning.

Sugar gums can become weeds not only in Western Australia, Africa and California, but in their native South Australia. They can outcompete and displace native species.

Sugar gums can become weeds.

Gregory Moore

A tree that leaves a lasting impression

I have been familiar with sugar gums since boyhood. Coming from the western suburbs of Melbourne, I remember lots of them in rows at the intriguing Albion Explosive Factory.

These trees left a lasting impression. I jumped at the chance to visit the site a couple of decades ago to inspect some of the trees before the factory closed. I still pass these trees as I travel along the Ring Road or Ballarat Road.

The site of the old Albion Explosive Factory is now largely the Melbourne suburb of Cairnlea. The last small parcels of land are about to be developed by the responsible state government agency.

Locals have fought a plan to remove sugar gum trees there. More broadly, though, many in the wider Australian community still see sugar gums only as risky trees that drop dangerous branches.

Lopping and topping

European farmers planted Eucalyptus cladocalyx in the early days of colonial farming, often in rows. It grew fast and formed good windbreaks.

These trees are capable of growth in heavy clay soils, drought tolerant and efficient water users. They were a tree that more or less looked after themselves in tough conditions.

The timber was also very useful for firewood, fence posts, and even furniture or building. It is a hard timber, though, and not easily worked even by skilled craftsmen.

Because it was used as a windbreak tree, sugar gum was often lopped or topped (removing the top of the tree) somewhere between two and four metres above the ground so the tree would branch out or bush up.

Some were regularly pruned at a lower height to encourage growth for the rapid production of firewood or fence posts. Even in city streets and suburban gardens, the practice was to top these trees so they would be bushy and shady.

But when you stopped lopping and topping, the shoots grew quickly. You ended up with the familiar long and spindly, multi-trunked trees so many of us know.

Quite often these long shoots just peel off from the tree or are blown off in a storm. This gives rise to the impression all sugar gums are structurally unsound and pose a risk from falling branches.

But this risk comes mostly from trees that are heavily branched, and multi-stemmed, which arises from being planted in poor soils and from intervention by humans. Left alone, they usually develop well.

Bees love the pollen from sugar gum blossoms.

Catzatsea/Shutterstock

A haven for native animals

Many sugar gums feature hollows and cavities, which become a haven for native fauna. These provide a home for a possum or two, but it is perhaps parrots that benefit most.

At certain times of year, there is a deafening din around sugar gums as sulphur-crested cockatoos, corellas and lorikeets jostle for nesting sites. It is an important breeding habitat for the endangered yellow tailed black cockatoo.

At other times, it is the quiet hum of bees collecting pollen from their small white flowers that draws attention .

This is what I think of when I see rows of old sugar gums in outer suburbs in small isolated parks. They remain as habitat refuges, when so many older trees have been removed for unimaginative land development.

Read more:

Early heat and insect strike are stressing urban trees – even as canopy cover drops Läs mer…

While the AUKUS alliance is new, the Australian-American partnership is not. As Australians reflect on the sacrifices of their soldiers on ANZAC Day, it’s worth remembering the first time Australian and American troops joined forces in battle – in northern France, in the final year of the first world war.

Australia fought as part of the British Empire in the early 20th century. This meant that when Britain declared war in 1914 against the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman empire), Australia immediately went to war on the side of the Allies (the British, French, Russian and Japanese empires, with Italy and the United States joining later).

The US didn’t fully commit to the Allied cause until April 1917. Once it did, it focused on building up its industrial war machine and recruiting troops to be sent to Europe. By July 1918, there were around a million American soldiers in France, with more arriving every day.

As I describe in my book, Coalition Strategy and the End of the First World War, from the Allied perspective, the war still very much hung in the balance. They knew the Germans were a formidable enemy, as the launch of the German Spring Offensives in March 1918 had shown.

The Allies had some battle successes beginning in June 1918 that slowly built their confidence. One of the important engagements would become known as the Battle of Hamel in northern France. This was when the Australian overall commander, Lieutenant General John Monash, spearheaded the first Australian-American attack in history. Monash organised the offensive for July 4, American Independence Day.

American and Australian troops dug in together during the Battle of Hamel.

Australian War Memorial

A quick victory, with limited casualties

Ahead of the battle, American forces moved into Australian lines. As Australian Lieutenant Edgar Rule described:

Twelve were put in each platoon, and believe me they were some men. This was the first time that they had been in the line, and they were dead keen; and apart from that it bucked our lads up wonderfully. All the novelty of the war had long since vanished for our boys … everyone was smiling or laughing.

The Yanks were out for information and our boys were very willing teachers, and it speaks well for the future to see one set so eager to learn and the other so willing to teach.

Despite Monash’s best intentions, however, the American supreme commander, General John “Black Jack” Pershing, was not pleased. Americans supporting Australia in a defensive role was one thing. Attacking, however, would involve higher casualty rates and reduce the strength of the US forces at a time when Pershing wanted to have his own sector of the battlefield, rather than have his troops fed into other armies.

Lieutenant General Sir John Monash.

Australian War Memorial

As a result, Pershing went so far as to withdraw six of his companies from the attack and then threatened to withdraw the remaining four. This treatment was not reserved for Monash. Many of the Allied commanders found Pershing difficult to work with – and Monash was no exception.

At 3:10am on July 4, 1918, Australian infantry, including four companies of the American 33rd Division, attacked the Germans in the town of Hamel. They moved forward under the protection of a “creeping barrage” (a slow-moving curtain of artillery fire that protects advancing troops and pins down enemy forces) and with the support of both aircraft and tanks.

Both the Australian Flying Corps and British Royal Air Force were used to prepare for and conduct the attack. This was the first major war in which armies used aircraft in large numbers. And the Battle of Hamel was the first time aircraft were used to parachute supplies to troops on the ground.

Sergeant Henry Dalziel of the 15th batallion.

Australian War Memorial

Within 93 minutes, the battle was over – and it was a success. The Australian-American forces had achieved their objective of gaining important ground – in this case, guarding the vital rail centre of Amiens – while limiting the loss of life. Casualties were comparatively low for the war, with around 800 killed.

An excerpt from the citation of an Australian Victoria Cross recipient, Private Henry Dalziel, illustrates how tough the battle was:

He twice went over open ground under heavy enemy artillery and machine-gun fire to secure ammunition, and though suffering from considerable loss of blood, he filled magazines and served his gun until severely wounded through the head.

His magnificent bravery and devotion to duty was an inspiring example to all his comrades, and his dash and unselfish courage at a most critical time undoubtedly saved many lives.

Dalziel survived the war and went on to be a songwriter.

Read more:

Poetry, parties and ’strong Australian tea’. The surprising story of how Anzac Day has been marked in the US for over 100 years

A rapid end of the war

Apart from demonstrating extraordinary courage, the Battle of Hamel is a case study of meticulous planning, excellent staff work and coordination of infantry, artillery, tanks and aircraft.

A soldier from the 15th battalion, worn out and asleep under camouflage which was found covering a German trench mortar.

Australian War Memorial

Indeed, the battle helped vindicate ideas about short, sharp attacks from mutually supporting Allied armies (which the Allied generalissimo, Ferdinand Foch referred to as “punching and kicking” the German lines), as well as the combined use of infantry, creeping barrage, tanks and aircraft. It had taken several years of battle experience to reach this point.

These ideas culminated five weeks later with the unprecedented Allied success of the nearby Battle of Amiens, which saw all available Australian spearhead the attack. It was Australia’s biggest victory of the war to that point.

The Australians also fought in the Battle of Mont Saint-Quentin in late August before again joining forces with the Americans and other Allied forces to smash through the Hindenburg Line in September.

By this point, it finally looked as though the tide had turned. The Allies began to envision an end to the conflict in late 1918 rather than in 1919, as they were planning for, Indeed, in less than two months, the fighting was over and the Allies were victorious.

Australian soldiers searching their German prisoners for souvenirs near Hargicourt, France, on October 1, 1918, after an attack on the Hindenburg Line outpost.

Australian War Memorial

For Australia, the end of the war could not come soon enough. The Hindenburg Line was the last offensive for them, as hard fighting over the previous two years had savagely reduced their troop numbers.

However, this was just the beginning of a long military partnership between the US and Australia, forged in shared battle experience and a growing trust, which has now lasted for more than a hundred years. Läs mer…

Since 1916, April 25 has been a de facto national day for Australia, commemorated as the occasion Australian and New Zealand troops began the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign in 1915. But for more than a century, Anzac Day has also been marked by Australians in the United States, via rituals ranging from songs and bingo to dinners and football games.

In 1922, 100 Australians congregated for an Anzac Day dinner at New York’s Hotel Pennsylvania, then the largest hotel in the world. Although this dinner was held only four years into the peace and with war memories still fresh, it was far from a sombre affair.

The event was an exuberant gathering, continuing well after midnight. Guests recited poetry and performed songs, with a telegram from Prime Minister Billy Hughes read to the assembled crowd. “On this day, sacred to or nation, Australians, wherever they may be, are bound together by the crimson tie of kinship,” Hughes wrote.

Later in the 1920s, there were Anzac Day events in Honolulu, Los Angeles, Chicago and Boston. These were upbeat social gatherings, quite different to the funereal Anzac rituals that emerged later in the century. At the time, Australians were still British subjects (not Australian citizens) and travelled on British passports. At this early stage, Anzac Day was about empire as much as nation.

These interwar dinners and dances were sporadic, ad hoc gatherings, not official commemorations. Before 1940, there was no Australian embassy or consulate in the US to organise state events, and the Australian community was small and highly assimilated into the local population. It would take another world war for April 25 to become an annual fixture in the US.

Read more:

Crowds at dawn services have plummeted in recent years. It’s time to reinvent Anzac Day

Clubs, dinners and a garden

The outbreak of the second world war in 1939 was accompanied by a dramatic upswing in Anzac activity in the US. That year, the Australian Society of New York was established to organise social events and fundraise for the war effort. The highlight of the society’s calendar was the annual Anzac Day dinner.

The 1942 dinner was a deluxe extravaganza organised by the Australian-born celebrity decorator Rose Cumming.

Held at the Waldorf Astoria, it was attended by 1,800 guests including British Ambassador Lord Halifax, Australian Minister for External Affairs H. V. Evatt and former US Presidential candidate Wendell L. Wilkie. British prime minister Winston Churchill and Australia’s John Curtin sent telegrams. The guest list included the rich and famous, with various Rockefellers, Vanderbilts and Rothschilds, alongside Hollywood star Merle Oberon.

Merle Oberon in 1943.

Wikimedia Commons

This New York dinner, held two months after the fall of Singapore, was a high-stakes affair, which sought to strengthen the newfound Australian-US alliance. Essentially a public relations exercise promoting the idea of Australia to an audience of US elites, it was a roaring success.

The evening was sponsored by corporate heavyweights such as General Electric, General Motors and Chase National Bank. South-Pacific Supreme Commander Douglas MacArthur cabled an effusive message of support.

In these war years, Anzac activity was not limited to Anzac Day. The Australian Society organised Anzac cocktail parties and bingo nights year-round. It also established an Anzac War Relief Fund to raise money for Australasian servicemen. In 1941, a Pacific Coast branch of the fund was established by Australians in Hollywood, an occasion marked by a glamorous party at the Riviera Country Club.

Hostesses and guests at the Anzac Club, New York, circa 1944.

State Library of Victoria

Then there was the Anzac Club. The brainchild of New Zealand actress Nola Luxford, the club was a home-away-from-home for Australasian servicemen in New York. After the New York club opened in 1942, other Anzac Clubs opened in Detroit, Boston, Chicago and Washington DC.

These clubs became de facto Australian embassies and were renowned for serving “strong Australian tea” – a rare pleasure in a coffee-drinking nation.

The Anzac Garden is on the roof of the Rockefeller Center’s British Empire building.

rblfmr/Shutterstock

During the war, New York also acquired an Anzac memorial garden, located atop the Rockefeller Center’s British Empire Building at 620 Fifth Avenue. The garden featured a central pool to represent the Pacific Ocean, bordered by three garden beds symbolising Australia, New Zealand and the US – a design anticipating the tripartite alliance formalised with the 1951 ANZUS treaty.

Since opening in 1942, the Anzac Garden has hosted annual Anzac commemorations. In 1943, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt attended the garden’s re-dedication ceremony, a publicity coup boosting awareness of the venue and promoting the Anzac cause. To this day, the Anzac Garden remains the only permanent Australian monument in New York City.

Read more:

Friday essay: do ‘the French’ care about Anzac?

Anzac resurgence

As in Australia, the past few decades have seen a resurgence of Anzac commemoration in the US. As thanks for Australian participation in the “war on terror”, in 2005 the Bush administration introduced the E-3 visa program, which made special provision for Australians to live and work in the US. As a result, the Australian population of New York City alone quickly grew from 5,000 in 2005 to 20,000 by 2011. By 2019, there were almost 99,000 Australians resident in the US.

For this expanded Australian diaspora, Anzac Day remains an opportunity to gather. In New York, April 25 is marked by social gatherings, as well as church services and Anzac Garden ceremonies. The city also hosts a Dawn Service at the Vietnam Veterans Plaza.

The Australian Embassy in Washington DC organises a regular Anzac Day event, as do Australian consulates in Chicago, Los Angeles, San Diego and Houston. In 2019, San Francisco had no fewer than four scheduled events, including a coffee meet-up, a sausage sizzle, a football game and a formal service.

Unlike the upbeat gatherings of the 1920s, these contemporary Anzac events tend to be sombre and moving, with tears often shed. Just as in Australia, Anzac Day in the US is becoming more emotional, rather than less, as the two world wars recede from living memory.

Throughout the US, special Australian rules football games are played on April 25, mirroring the Anzac Day clash between Collingwood and Essendon, which began in 1995.

In San Francisco, the Golden Gate football league plays an annual Anzac Day round, followed by an Australian lunch of meat pies and beer. Other Anzac gatherings serve iconic Australian foods like Tim Tams, lamingtons, meat pies, sausage rolls and – of course – Anzac biscuits.

These days good coffee rather than tea has become a marker of Australianness abroad. In the 2010s, Manhattan’s Australian-run Bluestone Lane café began serving free flat whites and Anzac biscuits to attendees from the nearby Dawn Service. The café’s San Francisco outlet also offered complimentary coffees.

One of New York’s Bluestone Lane cafes.

Shutterstock

Memorial diplomacy

April 25 has also become an occasion to reaffirm the Australian–US alliance. In recent years, Anzac services have been attended by high-ranking officials from both countries, who have used the occasion to emphasise trans-Pacific cooperation and friendship.

In 2021, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken noted that the “kinship our armed forces share” dates back to 1915. In 2022, former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull addressed New York’s Dawn Service, while former governor-general Quentin Bryce gave the Anzac Day address at New York’s Trinity Wall Street Church. Both speeches relayed the history of Australian-US wartime cooperation and stressed – in Bryce’s words – that “today is a day for all of us”. In 2024, Bryce will once again give the Anzac Day address.

This trend is an example of what historian Matthew Graves calls “memorial diplomacy” – the use of commemorative events to create or reassert geopolitical alliances. As the ANZUS treaty enters its eighth decade, Anzac Day in the US has been repurposed as a celebration of that strategic relationship.

In many respects, Anzac remains as much about empire as nation – only these days the British empire has been usurped by the American. Läs mer…

When the news broke last weekend that 23 Chinese swimmers had tested positive to a banned drug in early 2021 and were allowed to compete at the Tokyo Olympic Games six months later without sanction, many people – particularly in the Western world – immediately suspected a cover-up.

The US anti-doping boss, Travis Tygart, has been one of the most vocal critics of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), claiming the Chinese positive tests had been “swept under the carpet” by the body.

A few days later, the US Anti-Doping Agency stepped up its attacks, calling on governments and sports leaders to overhaul WADA and appoint an independent prosecutor to investigate the 23 positive cases in China.

WADA has been put on the defensive. It has threatened legal proceedings against Tygart for his “outrageous, completely false and defamatory remarks”. And it hosted a virtual media conference about the case, with a panel of the agency’s anti-doping heavyweights taking legal, scientific and sports governance questions for almost two hours.

WADA press conference on Chinese swimming doping allegations.

Reputational damage to WADA

Transparency is key to any organisation’s reputation. It is never a good look when a body like WADA is forced to respond to a story exposed by the media, in this case a German documentary and a New York Times report.

WADA has surely suffered reputational damage by not being open about the case when it unfolded three years ago. But it maintains it couldn’t have handled the situation differently because of the complexity of the global anti-doping framework between WADA and national anti-doping agencies.

It wasn’t up to WADA to make the details of the failed tests public – this responsibility rested with the China Anti-Doping Agency (CHINADA) because it had carried out the tests and investigated the positive results. To protect innocent athletes if no violation is found, no public announcement is required.

Given an investigation by the Chinese Ministry of Public Security found traces of the banned substance trimetazidine (TMZ) in a kitchen at the swimmers’ hotel, CHINADA ruled the positive tests were the result of accidental contamination. The Chinese swimmers were cleared without any public announcement.

WADA says China’s national anti-doping agency kept them abreast of events throughout their extensive investigation, which took place during strict COVID lockdowns and was impacted by a local outbreak of the virus.

Far from accepting CHINADA’s findings on the face of it, WADA requested the entire case file so it could conduct its own scientific and legal investigations – including speaking with the drug manufacturer to get the latest unpublished science on TMZ, and comparing the Chinese positive tests with TMZ cases in other countries, including the US. WADA ultimately determined there was no concrete evidence to “disprove” the possibility of environmental contamination.

Here are a few reasons WADA gave as to why in its press conference this week:

More than 200 swimmers competing in the Chinese National Championships were staying in at least two different hotels at the time. The swimmers who tested positive to non-performance-enhancing amounts of TMZ were all at one hotel.

There were fluctuating negative and positive results for the swimmers that were tested on multiple occasions, which were not consistent with deliberate doping techniques, including microdosing.

WADA found no evidence of misconduct or manipulation in the case file handed over by CHINADA.

WADA says it reviews between 2,000 and 3,000 cases of suspected doping every year. It is not unusual for the body to file an appeal challenging anti-doping findings.

For example, WADA challenged an Australian Football League decision to clear 34 members of the Essendon Football Club. It also appealed a decision by the world swimming body, FINA, to clear high-profile Chinese swimmer Sun Yang of wrongdoing for his conduct during a 2018 drug test.

According to WADA’s general counsel, Ross Wenzel, the difference between these cases and the more recent allegations against the Chinese swimmers was that the body accepted the “no fault” finding in the latter case. In the earlier cases, it did not.

He also said WADA received external legal advice that it would have had less than a 1% chance of winning an appeal in the TMZ case. According to WADA, everything was handled by the book, and if the body was faced with the same situation again, it would do nothing differently.

Has China been unfairly singled out?

So, has WADA succeeded in changing the narrative? Probably not.

Why? Because putting the words “China” and “doping” together is a lightning rod in the current political climate given the intense rivalry between China and the US.

Currently there are 23 people serving anti-doping suspensions in Australia. Do we feel personal or national shame for their wrongdoing?

Every time the US team marches into an Olympic Games, or steps up onto a World Championships medal podium, do we point at them while recalling memories of the US Postal Service cycling team and the banned-for-life cyclist Lance Armstrong?

But when it comes to China, many observers are quick to name and shame athletes, viewing every news story as some kind of proof the country must have a systemic, state-sanctioned doping program.

Stories in the media about a possible medal redistribution in the Tokyo Olympic swimming events have falsely raised the hopes of those who finished behind the Chinese athletes – and likely been an unwanted distraction for the Chinese team preparing for the Paris Olympics.

Olympic purists might want to believe the Games are above politics. But with the US facing a pivotal election, wars being fought around the world and both Russia and China being cast as threats to democracy, the geopolitical stakes at these games are far greater than the politics of doping.

WADA – like the United Nations and other organisations – finds itself in the cross hairs of the great power struggle of our time: a rising China and its challenge to US dominance. Läs mer…